The emergence of firearms control regulations is linked to the attempts of modern states to establish a monopoly over the use of force. The development of the firearms legal frameworks was gradual and, in some cases, strongly influenced by historic circumstances and reflects the perception of threats to the society and to the individual. Sometimes occasional events such as mass shootings can further influence the development of restrictive policies.

German legal tradition does not foresee bearing arms as a constitutional right. The evolution of the national firearms regulations is closely linked to the historical developments in the country and started with the introduction of a licensing system for firearms ownership through the Firearms and Ammunition Act of 1928. This step was triggered by the existing widespread possession of firearms in private hands as a result of the First World War (Oswald, 1986). The Hitler regime enacted several restrictive regulations with the goal to remove firearms concentrated in the hands of their political opponents, followed by a more lenient Firearms Act in 1938 (Oswald, 1986).

In the United Kingdom, two firearms related incidents had an important impact on national firearms legislation. In 1987, Michael Ryan used rifles that he lawfully owned to shoot and kill sixteen people. In 1996, sixteen children at an elementary school in Dunblane, Scotland, were killed by Thomas Hamilton, also with his lawfully held firearms. In the first instance, a ban was introduced through an amendment of the Firearms Act prohibiting the ownership of high-powered rifles, whereas after the Dunblane shooting an amendment to the same act was adopted, which severely restricted the private ownership of firearms (Barnett, 2017).

In 2019, New Zealand witnessed the deadliest shooting in the country's modern history after 50 people were killed and 20 more seriously injured at two mosques in the city of Christchurch. The attacker had streamed live the shootings before they were removed from social media sites. Six days after the attacks New Zealand introduced sweeping firearms law changes by banning the sale of assault rifles and military-style semi-automatics (MSSA), banning parts that can be used to convert firearms into MSSA weapons, and by introducing a buy-back scheme for MSSA weapons across the country.

Today, firearms are regulated at national level through constitutions and primary legislation, i.e. legal acts passed by a legislative institution such as a parliament, national assembly or a congress, as well as through secondary legislation. Secondary legislation, also referred to as subsidiary legislation, takes the form of regulations, orders, rules, instructions, bylaws, guidelines, etc., which are adopted by the executive branch of the government and provide details on how to implement the primary legislation.

The scope of the national regulations encompasses the life cycle of firearms, and regulates the activities associated with their manufacture, marking, possession, use, transfer, storage, destruction and in some cases, deactivation and re-activation regardless of whether or not the country is party to a global or regional instrument on firearms control. Within the scope also fall the provisions for establishing authorities responsible for its implementation, such as various licencing authorities which will control the processes of manufacture, possession or transfer of firearms, as well as provisions regulating the activities of specific actors, including private security companies and brokers. The scope includes sanctions for not adhering to the established rules, time limits for exercising the authorized activities, and requirements for implementing specific security measures to prevent theft and diversion of firearms.

The scope of national legislation does not necessarily overlap with the scope of the relevant international instruments. Most often domestic laws have a larger scope of application as they often refer to a broader range of arms, including explosives, which are not covered in the international instruments on arms control, and regulate specific requirements in a more detailed manner.

By way of example, the Protocol against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Their Parts and Components and Ammunition (Firearms Protocol), supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), focuses on the criminal justice dimension of illicit manufacturing of, and trafficking in, firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition, and on those aspects that are relevant for the prevention, investigation and prosecution of these offences. As such, the Protocol remains silent on other aspects linked but not essential to its objectives, or that Member States deliberately decided to leave to national laws to define, such as the issue of civilian possession and ownership of firearms. The same can be said about the Arms Trade Treaty, which focuses on the regulation of the legal trade and which leaves to national decision makers the choices regarding enforcement, sanctions and international cooperation measures mentioned but not further developed in the Treaty.

Often, the provisions contained in international instruments remain either generic or implicit in some requirements leaving it to national legislators to determine the specific content. One such example is contained in Article 13 of the Firearms Protocol, which requires State parties to take appropriate security and preventive measures at the time of manufacture, import, export and transit through the territory, and to increase the effectiveness of import export and transit controls. These include border controls and police and customs cross-border cooperation in order to detect, prevent and eliminate the theft, loss or diversion of, as well as the illicit manufacturing of, and trafficking in, firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition. The provision does not supply further guidance on the type of measures that should be put in place to obtain the expected result. Similarly, Article 10 of the Protocol envisages that each State party shall establish or maintain an effective system of export and import licensing or authorization, but it does not prescribe whether such system should be embodied in a single agency, or should be performed through inter-agency mechanism. Neither does it provide guidance on the various types of licences that can be issued. These requirements are established in greater detail in the domestic laws.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of topics covered by national firearms regulations and some illustrative examples of national application that showcase the diversity of domestic firearms control regimes.

The manufacture of firearms is subject to authorization and regulation by relevant national authorities. Usually the national legislation includes a general provision prohibiting this activity and detailed regulations of the actors, and the requirements which they should meet to engage in such activity. Not all countries manufacture firearms; those who do not, import firearms for their public and private needs. Where there is a manufacturing industry, this can be either in the hands of the state, as part of its monopoly, or in the hands of private or semi-private companies. In this latter case, these entities are subject to state authorization or licence to manufacture firearms, parts and components, or ammunition.

In Brazil, article 21 (VI) of the Constitution stipulates that the federal Government has the power to authorize and supervise the production and trade of armaments. Section 9 of the Decree No. 3.665 provides that the activities concerning the manufacture of controlled goods, including firearms, must be registered by the Army, which will issue a relevant Registration Title. In South Africa, Section 45 of the Firearms Control Act specifies that no person may manufacture firearms, muzzle loading firearms, or ammunition without a manufacturer's licence. Similarly, Section 38 (1) of the Firearms and Ammunition Control Act of Tanzania specifies that a person shall not manufacture or assemble firearms or ammunition, except in accordance with the terms of the permit issued by the Armament Control Advisory Board.

The authorization to manufacture firearms is issued after the applicant meets specific requirements defined in the national legislation by a competent authority. The manufacture of firearms and ammunition without such authorization is considered an offence in most countries in the world. By way of example, Section 4 of the Firearms and Ammunition Act of the Solomon Islands foresees that any person shall be guilty of an offence and liable to a fine of five thousand dollars or to imprisonment for ten years, or to both such fine and such imprisonment, if s/he manufactures any firearm or ammunition except at an arsenal established with the written approval of the Minister and in accordance with such conditions as the Minister may from time to time specify in writing. Similar provisions can be found in many other national legal systems.

The requirements for manufacturing firearms contain criteria against which the relevant national authority assesses whether the applicant is competent and/or suitable to perform the activity. Such requirements can include, for instance, the fact of not having any previous convictions, having a specific proven knowledge of the subject matter, a specific age limit, certain security conditions of the production premises, availability of sufficient capital, etc. Article 14 (1) of the Bulgarian Act on Arms, Ammunition, Explosives and Pyrotechnics prescribes amongst others that persons who wish to produce arms must have at their disposal sites for production and storage, owned or rented, which meet the requirements for physical protection, qualified staff, security officials, and specialists who keep control over the movements of the production items.

The authorizations for manufacture are usually limited in time and narrow down the scope of the items that can be produced. Upon expiry, they can be subject to renewal when specific conditions are fulfilled. Section 49 of the Firearms Control Act of South Africa foresees that the holder of a manufacturer's licence who wishes to renew the licence must apply to the Register for its renewal in the prescribed form at least 90 days before the date of expiry of the licence. No application will be granted unless the applicant satisfies the Registrar that he or she has continued to comply with the requirements of the licence in terms of the Act.

During the licencing period, the manufacturer needs to comply with regulations linked to record-keeping and marking of the produced firearms and maintaining safety and security procedures. In the Czech Republic, regulations of the Firearms Proofing Act and its Implementing Regulation No. 335/2004 oblige manufacturers to stamp a serial number, model name, country of origin, and calibre, and to place the markings on at least one of the main parts of the weapon, whereas the serial numbers must appear on the barrel, frame and breech. The markings should be affixed during the production process before the final assembly. After fulfilling this requirement, the firearms can be submitted to the Czech Arms and Ammunition Proofing Authority for testing.

National regulations also foresee the right to exercise oversight of the production process and engage in regular inspections. The purpose of such inspections is to verify whether the licensee adheres to the various legal requirements governing the manufacturing process. These inspections are also a form of enforcement of the national firearms regulations. In South Africa, a police official or any person authorized by the Registrar may enter any firearm or ammunition factory, or place of business, of a manufacturer and conduct such inspection as may be necessary in order to determine whether the requirements and conditions in the national legislation are being complied with (Section 109 of the Firearms Control Act).

Another area where national manufacturing regulation is relevant refers to the emerging phenomenon of illicitly converted arms and reactivated firearms. To the extent to which national legislators and policy maker fully transpose and implement the Firearms Protocol requirements on illicit manufacturing and deactivation of firearms, they will also be able to better address emerging threats, such as the problem of illicitly converted and reactivated firearms in Europe. In practice, findings of the terrorist attacks in France in 2015 revealed that several of the weapons used were converted firearms (Candea, 2016). It soon appeared that important legal loopholes on illicit manufacturing and on deactivation standards within the EU and among its Member States had in part contributed to the paradoxical situation whereby private persons could legally buy gas firing and alarm pistols manufactured in Turkey, which were capable of being easily converted into functioning firearms.

National legislation includes requirements for assigning a unique identifying mark to each firearm. The marking of firearms is a fundamental prerequisite for successful tracing and investigation of firearms offences, including firearms trafficking. The scope of marking includes the time when the marking should be applied, the information which should be included, and who should apply the marking. The legislation further prescribes the technical requirements to be observed during the marking process, including the size of the font or the depth of the marking.

Firearms are marked at various points during their lifecycle. The initial marking is placed during the manufacturing process and it includes information about the main identifiers of the firearm. In Brazil, the firearms manufactured in the country must bear the following information: name or brand of the manufacturer; name or code of the country; calibre; serial number; year of manufacture (Article 5 of the Ministerial Act No. 7). Another type of marking - the import marking - will be applied when the firearm leaves the country of the manufacturer and is transferred to another country. It increases the efficiency of the tracing process. When criminal justice authorities initiate the international phase of the tracing procedure, they will not lose time by submitting requests to the manufacturing state, but will instead reach out to the authorities of the state that has imported the firearm.

The import marks provide information about the country and year of import. Some countries place higher requirements on the import marking process by requesting additional information to be marked and by enlarging the scope of marking. In Switzerland, the law provides that imported firearms, their essential components and accessories, should be assigned with the following additional identifiers: the three-letter country code of Switzerland " CHE"; the marking number of the licensed gunsmith who performed the marking; and the last two digits of the year in which the objects were introduced into Switzerland (Article 31, 2008 Weapons Ordnance).

In some countries, the legislation specifies the technical requirements for import marking, including the methods of marking and locations for marking. In Lithuania, the import marking can be applied through laser engraving, press marking or roll stamping and the font size used for marking should be 2 - 2.5mm. and should be placed in a location that is not understood as part of the manufacturer's initial marking (Order 5-V-753). The obligation to apply the import marking rests with the entity which imports the firearms. The import marking is applied by licensed organizations and importers. Proof marks applied by the Proof Houses in the countries participating in the Convention for the reciprocal recognition of proof marks on small arms on imported firearms are also considered to fulfil the requirements of import marking, since the Proof Houses keep records on the serial numbers of the tested firearms and time of testing.

Further marking can be applied as follows: at the time of acquisition by state security services marks can be applied indicating the service and unit to which the firearm is assigned; at the time of transfer from governmental stocks to permanent civilian use; at the time of seizure, if the firearm does not have markings and it will be retained by the state; and at the time of de-activation.

The national legislation foresees requirements for keeping records on firearms, their parts and ammunition, and this obligation is imposed on several actors. The manufacturers need to comply with record-keeping requirements related to their production and maintain comprehensive information about the production process. Such information usually includes the date of manufacture and the quantities of firearms produced, as well as serial number, make, model and calibre, and information about sales of firearms. Records should be kept in paper form or electronically and updated on a regular basis. Further, records should be kept for a sufficiently long period to allow the retrieval and tracing of older firearms, although there is no clear rule on this. As has been seen in Module 5, the Firearms Protocol and the Arms Trade Treaty require State parties to keep records for at least ten years, while the non-binding International Tracing Instrument recommends that data should be ideally kept for ever, without any limitation in time. Regional instruments, too, do not follow a unified approach. Section 23 of the Law of Weapons in Germany stipulates that anyone who manufactures firearms commercially shall keep a weapons register recording the type and quantity and whereabouts of the guns. In Bulgaria, the law provides that manufacturers should keep a registry for a period of ten years from the date of production of firearms or ammunition (Article 31 (1) of Act on Arms, Ammunition, Explosives and Pyrotechnics). The registry should contain information about: the quantities and the date of firearms produced; information for the identification of the produced firearms; name and address of the person who has delivered the firearms' parts or components when the licensee only assembles firearms; name and address of the person who has received the firearms. The manufacturers should share this information with the Ministry of Internal Affairs periodically, such as every quarter, by submitting both a hard and electronic copy of the data.

Similar registries should be maintained by the firearms dealers, who should keep information about their stocks of firearms and the transactions that have taken place. Shooting clubs and private security companies shall also maintain records of the firearms in their possession.

There are also regulations specifying that institutions authorizing civil ownership shall keep information about the issued licences and collect data on the firearms in civilian possession. The same requirement is envisaged for state institutions - army, police, penitentiary services - who should maintain records of their stocks and service weapons.

The access to firearms and ammunition by civilians, their ownership and use, is subject to governmental controls in all countries of the world. The main reason for this is the fact that firearms can cause injuries and death. National practices may vary significantly in this field. As was illustrated in Module 1, the approaches range from countries that take a very restrictive stance and do not allow civilians to have firearms at all (with few exceptions), to countries that go in the opposite direction and consider owning a firearm as a constitutional right. National laws and regulations on ownership and possession usually focus on establishing control over certain types and characteristics of firearms to which civilians may have access, and on defining the ones that are prohibited by law to them, as well as on the civilian uses of firearms, civilian users of firearms, on the commercial sale of such firearms, and the use of firearms in general (MOSAIC 3.30).

Not all firearms can be freely acquired by civilians. In many jurisdictions the acquisition of automatic firearms and armour-piercing ammunition has been banned. In Russia, the law prohibits the possession by civilians of the following types of firearms: any automatic long-barrelled firearm with a magazine capacity exceeding 10 rounds; automatic firearms designed to imitate other models, cartridges with armour piercing bullets, etc. (Section 6 of the Federal Law on Weapons). In Lebanon, the law states that civilians should not own weapons of any size and calibre intended for military use, machine guns of all kinds, sizes and calibres, all kinds of ammunition for such weapons, etc. (Article 25 of the Weapons and Ammunition Law). In Spain, private individuals cannot possess automatic firearms, those disguised as other objects, or armour-piercing ammunition (Article 4 of the Law on the Protection of the Security of the Citizenry). The current Firearms-Control Law (1996) of the People's Republic of China, for example, foresees the individual ownership of firearms only under exceptional conditions. Only individuals who are engaged in specific profession or exercise a regulated activity, like wildlife protection, sports shooting and hunting are permitted to own rifles. On the other hand, they are not permitted to move with their firearms outside of the pre-established hunting or pastoral grounds (Article, 6, 10 and 12 of the Firearms-Control Law). On the opposite side, the constitutional provisions of Mexico, Guatemala and the United States of America grant their citizens the right to possess and bear firearms. Article 10 of the Constitution of the United Mexican States provides for the right to possess firearms in homes for the purpose of legitimate defence and security. Article 38 of the Constitution of Guatemala recognizes the right to own firearms for personal use not forbidden by law in a person's home, and the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution grants the right of the people to keep and bear arms.

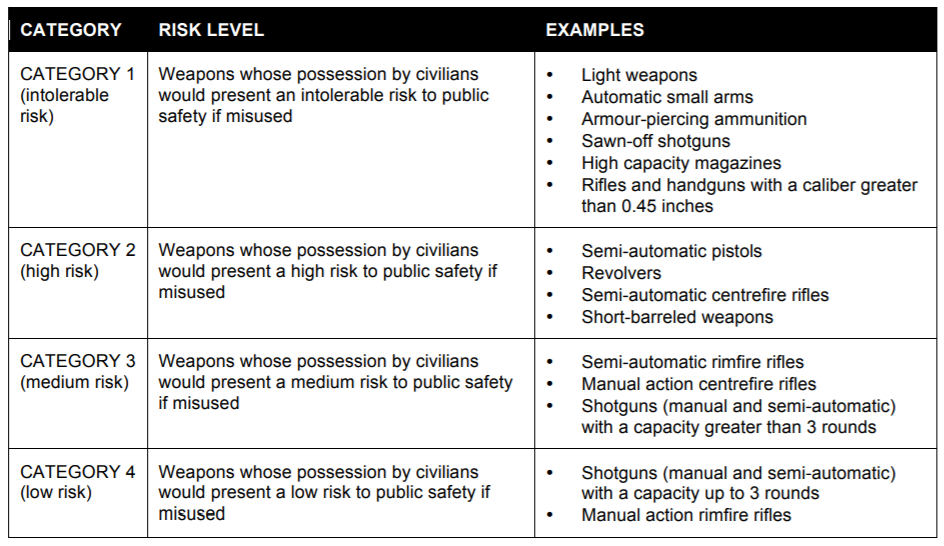

When imposing bans on specific categories of firearms, legislators take into consideration various constitutional, cultural and historical factors. Furthermore, they apply risk analysis, which is then reflected in the firearms categorizations. The table below provides an example of how firearms can be categorized based on identified risk level.

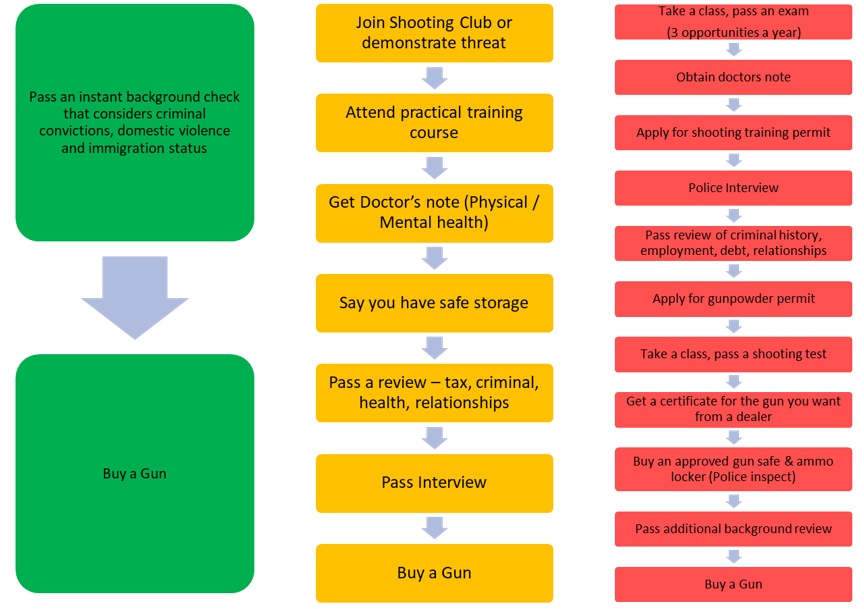

The question of who should be permitted to possess a firearm is not regulated internationally, and it is left to national regimes to control. While every state has the sovereign right to determine which types of use and user are legal, some general standards as to legitimate use have developed over time. MOSAIC 03.30 has summarized the legitimate uses of firearms in the following categories: " hunting, sport shooting, the provision of private security services, self-protection, collection, and other activities such as historical re-enactment, historical research, theatre, television, film, the humane dispatch of animals, sporting events (e.g. starting pistols or cannon)." The Firearms Protocol mentions explicitly hunting, sport-shooting, collections and repairs as legitimate, verifiable purpose for owners to temporarily export their weapons. In Japan, the law grants possession for a specific reason such as hunting, target shooting or extermination of harmful birds and animals (Article 3 and 4, Law Controlling the Possession of Firearms and Swords). In articles 96-99 of the Law on the Protection of the Security of the Citizenry, Spain requires applicants to establish the reason for obtaining a firearm, which can include hunting, collection, self-defence, target shooting or security reasons. National legislation establishes a licensing regime for firearms' possession and imposes specific conditions for obtaining various categories of licences. The required steps to obtain such licence will differ from country to country in both the information required to supply to the national authorities and the number of steps necessary to issue a licence.

For illustrative purposes, a comparison between the United States (green colour), India (yellow colour) and Japan (red colour) is reproduced graphically below, which is based on the study on how an individual can purchase a firearm in fifteen different countries (Carlsen and Chinoy, 2018). The process, as exemplified in the table below, is simplified to some extent as the United States has 50 States which may have their own firearms purchase laws and some of these will be more restrictive or less restrictive.

The national regulations envisage various criteria, which individuals must fulfil before obtaining a firearm. As can be seen in the examples depicted in the figure above, the level of exigencies can vary significantly from country to country. In Tanzania, the law specifies that a person must be 25 years old, must obtain a certificate of competency, is mentally stable and not inclined to violence, is not dependent on any substance with an intoxicating or narcotic effect, has not been convicted, etc, in order to be issued with a licence to possess a firearm (Article 11 (1), Firearms and Ammunition Control Act). In Norway, permission to purchase a firearm may only be given to reliable persons of sober habits who need or have other reasonable grounds for possessing firearms, and who cannot be deemed unfit to do so for any special reason (Article 7 (1), Act No. 1 Relating to Firearms and Ammunition). The Firearms Law in Israel, among others, obliges persons to have proper training on how to use the firearms for which an application has been placed (Section 5C of the Firearms Law). The Firearms Regulations implementing the law establish training programmes from which the person needs to graduate before receiving the licence. In Nigeria, the Firearms Act (1990) regulates the possession of, and dealing in, firearms and ammunition. For the implementation of the Act, the Government adopted subsidiary legislation in the form of Firearms Regulations, which provide detailed information about the duration of the licence to possess firearms and the procedure for its renewal. Furthermore, the Firearms Regulations for the implementation of Section 33 of the Act determine, among others, the role of the Inspector-General of Police in maintaining the register of firearms and licences and the application process for various types of firearms.

Legal persons can also apply and obtain licences to possess firearms when they fulfil specific requirements. National legislation foresees that the operations of private security companies and shooting clubs should be regulated and that they should abide by existing firearms regimes. In Germany, the need for security companies to acquire, possess and carry guns is recognized, if they can credibly demonstrate that security contracts are being or are to be performed, which require firearms in order to protect a person in danger or an endangered property (Section 28, Law on Weapons). The Law further specifies that the firearm can be carried only while carrying out a specific contract and the security company shall take suitable measures to ensure that security staff also comply with this requirement. In Germany, the legislator also imposes strict reporting obligations for security companies. They need to report to the competent authorities the names of the security staff who are to possess or carry the licence holder`s firearms on his instructions under the terms of an employment contract. The security companies cannot transfer the firearms and ammunition to their personnel until the competent authorities have provided their consent.

Also shooting clubs are generally subject to authorizations and state control. The Home Office of the United Kingdom has imposed extensive criteria which shootings clubs should meet before receiving a licence to operate as such. The club needs to be a genuine target shooting club with at least ten members at all times and must have a written constitution. It must appoint a member to act as a liaison officer with the police, to maintain a register of the attendance of all members together with details for each visit, and the firearms they have used. The club needs to inform the police of any holder of a firearm certificate who has ceased to be a member for whatever reason (Home Office, 2012).

National legislation also contains regulations on weapons possessed or used on behalf of state institutions. Such regulations govern the regime of storage and stockpile management of firearms and their ammunition by various governmental agencies and their use by state employees. Stockpile management provisions regulate further the stockpile composition, stockpile locations, physical security, record-keeping procedures, risk assessments, determination of surplus stocks and transportation of firearms. The importance of adequate stockpile management cannot be underestimated. As outlined in Module 4 on The Illicit Market in Firearms, unsecure government stocks become often the target of criminals to gain access to weapons.

The use of firearms by state institutions, such as police forces, is regulated in primary and secondary legislation. The regulations can foresee both the need for obtaining a permit for using the firearm as well as exemption from this requirement. In South Africa, an employee of the Defence Force, Police Service, Department of Police Service, or Correctional Services may not possess a firearm without a specific permit (Sections 95 and 98, the Firearms Control Act). The members of the Defence Force are exempted from the obligation to have a permit in respect of military firearms issued to them while performing official duties under military command (Section 98, Firearms Control Act).

National legislation on transfer controls includes regulations over import, export, transit, transhipment and brokering activities. The basis of the regulation is the issuance of authorization to undertake any of these activities, after fulfilling a set of requirements established in the law. The authorization is issued by a competent national authority, which reviews the application, collects further information on the request, in some cases engages in consultations with other national institutions, and reaches a decision to grant or deny the authorization. In Germany, all requests for granting authorization for transfers of firearms are processed centrally by the Federal Office for Economy and Export Control, whereas in Bulgaria, the Inter-ministerial Commission for Export Control and Non-Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction reviews the applications for firearms transfers by drawing on the expertise of officials from several national institutions.

Many national legislatures also include a list of goods, including firearms, which should be subject to transfer controls. These lists are periodically reviewed and updated. In Australia, the Defence and Strategic Goods List (DSGL) provides information about the goods which fall under transfer regulation, and represents a compilation of military and commercial goods. Part 1 of the DSGL covers goods that are " inherently lethal" as well as defence and related goods. The Munition list 1 (ML1) contains information about various types of firearms that are subject to control, including rifles and combination guns, handguns, machine, submachine and volley guns.

The list of controlled goods identifies to the prospective importers or exporters goods for which they have the obligation to obtain an authorization from the relevant national institution through the submission of an application. In the application, they provide information as specified in the national law. In Estonia, in order to obtain an authorization in the form of a licence, the applicant must provide information about name, address, personal identification code or date of birth if the applicant is a natural person, and/or the registry code of a legal person. Furthermore, the same data will be collected of the recipient of the goods or service and the end-user of the goods (Section 13, Strategic Goods Act). The information about the end-use and the end-user is usually contained in an End-User Certificate, issued by the importing state.

The application must also contain: a description of the goods or service and the field and place of end-use; the country and place of location; the country of origin; the country of consignment and the country of final destination of the goods; the ISO codes of the specified countries; the code of the customs-approved treatment of the goods; the journey of the goods from the country of consignment to the end-user; the period of time for the import, export or transit of the goods or for the provision of the service and the transfer time of software and technology; the quantity and value of goods; the marking of a weapon and essential components of the weapon if this is required by the Weapons Act, etc. (Section 13 of the Strategic Goods Act).

The national authorities review the submitted application and assess it against pre-defined criteria. State parties to the Arms Trade Treaty are required to undertake risk assessments to establish whether the exported items would contribute to, or undermine, peace and security, and whether they could be used to commit or facilitate a serious violation of international humanitarian law, commit or facilitate a serious violation of international human rights law, commit or facilitate an act constituting an offence under international conventions or protocols relating to terrorism to which the exporting state is a Party, or commit or facilitate an act constituting an offence under international conventions or protocols relating to transnational organized crime to which the exporting state is a Party (Article 7 of the Arms Trade Treaty). Based on the results of the assessment, a licence will be granted or the application will be denied.

Many countries require control over the movements of transferred firearms after the licence for export has been issued by prohibiting their re-export. The End-User Certificate requested by the Serbian Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunication requires the importer to agree not to divert, re-export, or trans-ship the firearms to any other person or country without the written permission of the competent authorities of Republic of Serbia. As part of the post-shipment control, the importer also agrees to confirm receipt of the goods upon request by the competent Serbian authorities.

National legislation on transfer controls also regulate the activities of natural or legal persons who act as brokers. The brokers provide services related to the import, export, transit and trans-shipment of firearms. These services can include: " prospecting (identifying potential buyers and sellers); offering technical advice, for example, on weapons systems, modalities for transport and financing, and general features of the deal; sourcing, that is, identifying the types and quantities of required weapons, enquiring on prices and payment schemes, etc.; mediating negotiations; arranging financing schemes for the relevant transaction; obtaining necessary documentation, including end-user certificates, import and export authorizations; organising transport of the ordered weapons (Small Arms Survey, 2001)".

In Albania, the brokering activity is defined as any action carried out by either a legal or natural person, facilitating (acting as an intermediary) conduct of international transfers of goods designed for military purposes, including actions relating to financing and transportation of shipments, irrespective of the origin of these goods and the territory in which such activity will take place (Article 2 of the Law No. 9707). Natural and legal persons are usually required to register as brokers and the States maintain a database of registered brokers. The registration in most cases is for a limited duration and subject to renewal. In Estonia, the brokering services can be provided for five years after the registration (Section 55 of the Strategic Goods Act).

A more recent phenomenon that requires national legislators and policymakers to update and strengthen their firearms control regime regards the control over transfers conducted or enabled through the internet or the darknet, which is increasingly being used to support or enable the illicit trafficking in firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition, and which requires a review and enhancement of domestic transfer control regimes inter alia.

The national regulations envisage requirements for safety and security of the existing stockpiles. These regulations are usually issued by the relevant national services that own and use firearms and ammunition. The regulations provide guidelines on the storage conditions, including amount of firearms and ammunition that can be safely stored in one location, security measures that should be implemented to guarantee prevention of theft, monitoring of the conditions under which firearms and ammunition are kept, and the shelf life of ammunition where upon expiration of specific duration, based on the type of ammunition, it should be disposed of and replaced by new ammunition.

The destruction and deactivation of firearms are methods for disposal, with which the life-cycle of a firearm reaches its end. The destruction renders the firearms " permanently inoperable" and is the preferred method of disposal (MOSAIC, 05:50). National legislation contains various requirements for the destruction of firearms. In Tanzania, any firearm or ammunition relating to an offence shall be destroyed, as well as any firearm or ammunition found in any building, vessel, aircraft or place without any apparent owner (Section 56 and 57, Firearms and Ammunition Control Act).

The deactivation of firearms is regulated at global level by the United Nations Firearms Protocol, which sets the general principles for deactivation: all essential parts of the firearm should be rendered permanently inoperable and incapable of removal, replacement or modification in a manner that would permit the firearm to be reactivated in any way (Article 9). In Canada, the authority administering the Firearms Registry has adopted the Canadian Firearms Registry Deactivation Guide, which should be followed during the process of deactivation. For deactivation of firearms of calibre 20mm or less, including semi-automatic, fully automatic, selective fire, and converted firearms, a hardened steel blind pin of bore diameter or larger must be force fit through the barrel at the chamber, and where practical, simultaneously through the frame or receiver, to prevent chambering of ammunition. Further, the barrel must be welded to the frame or receiver to prevent replacement and the receiver must be welded closed to prevent replacement of the breech bolt.

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in France in 2015, it was established that as well as converted weapons, several of the weapons used were deactivated firearms that had been illicitly reactivated (Candea, 2016). The policymakers in the European Union (EU) identified a lack of legislative harmonization and the existence of loopholes in the European legislation governing the deactivation of firearms. As a result, the EU adopted binding legislation, the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/337 of 5 March 2018 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2403 establishing common guidelines on deactivation standards and techniques for ensuring that deactivated firearms are rendered irreversibly inoperable, obliging its Member States to follow stiffer guidelines on deactivation standards and techniques for ensuring that deactivated firearms are rendered irreversibly inoperable. The new rules also foresee the placing of a unique marking on the deactivated firearms and regulate the transfer of deactivated firearms within the EU.

National firearms legislation imposes various sanctions on individuals and legal entities when they are found to be not in compliance with firearms regulatory regimes. The sanctions can be of administrative or criminal nature. The administrative process regulates the interaction between private persons and legal entities with the state institutions, in this case, the authorities responsible for issuing various types of firearms licences. When an individual or a legal entity is found in violation of the established procedures, such as a breach, in some jurisdictions this can be defined as an administrative offence and the sanction is usually a fine. Section 76c of the Act on Firearms and Ammunition of the Czech Republic provides that a legal entity or a natural person commits an administrative offence if they acquire or possess a firearm and ammunition without a licence, and such a violation can be sanctioned by a fine of up to CZK 50,000 (ca. USD 2,228). Other national legislation defines the possession of a firearm without a licence as a crime and imposes criminal sanctions for such conduct. For example, the Criminal Code of Canada, in Section 91 (1), criminalizes the possession of a firearm without being a holder of a licence and a registration certificate for the firearm resulting in a punishment of imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years.

National firearms laws also establish the institutions which will be responsible for the implementation of the firearms regulations and enforcement of the envisaged sanctions when the regulations are not followed. The designation of such institutions follows the lifecycle of the firearms and can vary from country to country, and sometimes one activity can be regulated by several institutions. In some jurisdictions, the Ministries of Defence or Economy will be responsible for issuing authorizations for firearms manufacturing and monitoring the compliance of producers with the legal framework. Monitoring of security in the production facilities can be a shared responsibility between the Ministries of Defence and Interior. The civilian possession of firearms will be usually enforced by the Ministries of Interior, who will be issuing licenses for possession, use and carrying of firearms. The Ministries of Interior will also be responsible for the management of their stockpiles and service firearms. The Ministries of Defence will be responsible for regulating the stockpiles and use of weapons belonging to the army.

International transfers of firearms will fall usually under the jurisdiction of the Ministries of Economy and Defence. In many countries the authorization for transfer will require a consultative process with other national authorities, including the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Security Services. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also lead the process of adherence to international instruments and the respective negotiations, supported by the Ministries of Defence, Interior and Justice. The Ministries of Justice will be responsible for harmonizing national criminal laws with the sanctions envisaged in UNTOC and the Firearms Protocol. The record-keeping obligations will be monitored by the Ministries of Interior for firearms in civilian possession and the Ministries of Defence for the weapons belonging to the army. The destruction and de-activation of firearms will be again a joint responsibility between the Ministries of Defence and Interior.

To better coordinate these functions internally, and facilitate the interaction with other countries and internationally, several countries have established inter-institutional bodies. These can take different forms and shapes, and their functions can range from a simple consultative role to a more active policy-setting and implementation remit. Multiple international and regional instruments require their members to designate national focal or national coordinating bodies: the Firearms Protocol, and the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives, and other Related Materials (CIFTA), require State parties to designate a national body or focal point to act as liaison among them and other State parties for all matters relating to the implementation of these instruments; the United Nations Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons and several Africa Conventions also recommend or require Member States to establish National Commissions (Article 24 of the Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons, Their Ammunition and Other Related Materials (ECOWAS Convention), Article 17 of the Protocol on the Control of Firearms, Ammunition and Other Related Material in the Southern African Development Community Region (SADC Protocol) and Article 27 and 28 of the Central African Convention for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons, Their Ammunition and All Parts and Components That Can Be Used for Their Manufacture, Repair and Assembly (Kinshasa Convention)). EU Member States are required to establish Firearms Focal Points. The terms vary, but essentially the suggested functions of these coordinating bodies remain similar, and that is ensuring coherence, coordination and effectiveness among the various institutions that have a specific role to play within national firearms control regimes, and promote and facilitate regional and international cooperation in this field.

Colombia, for example, established in 2006 a National Coordination Committee to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trafficking in Small Arms and Light Weapons in all its Aspects. The Committee is chaired by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and has among its functions that of developing and overseeing the implementation of a National Action Plan on SALW. In Africa, several countries have established National Commissions, often placed directly under the Presidency, such as Burkina Faso and Ghana. EU Member States have established national focal points, which gather periodically under the European Firearms Expert Group - EFE, composed primarily of law enforcement agencies, and in charge of promoting and facilitating the information exchange and cooperation in detecting and combating illicit firearms trafficking. A similar approach is also currently being followed in the Western Balkans with the establishment of focal points and the equivalent SEEFEN Group.