Wildlife crime can occur at the micro-level (such as subsistence poaching and individual acts of cruelty), meso-level (such as domestic trade in resident vulnerable species and organized illegal hunts), and macro-level (notably import and export of endangered species for international trade) (Wellsmith, 2011).

Wildlife trafficking involves a range of actors involved in poaching, trapping, harvesting, supplying, trading, selling, possessing, and consuming wild animals, animal products, and plants. These actors differ not only in the role they play along market chains, but also in their socioeconomic attributes, preferences, and motivations, in the scales of their operations and the intensity of their activity, the levels of technology and investment, their source of funding, level of economic reliance, and their skill and knowledge, including that of relevant laws and regulations. Actors can occupy multiple roles in wildlife trafficking, with a wide range of motivations that are both context-and value-dependent, and that can change over time. Some target their activities specific species, while others operate more broadly (Phelps et al, 2016; see also the findings of Warchol, 2004). The range and number of individuals involved in wildlife trafficking depends on a number of factors, including the expected end market and anticipated consumers, the unique characteristics of the trafficked item, and the capabilities and limitations of actors already involved in the trade (Pires & Moreto, 2016).

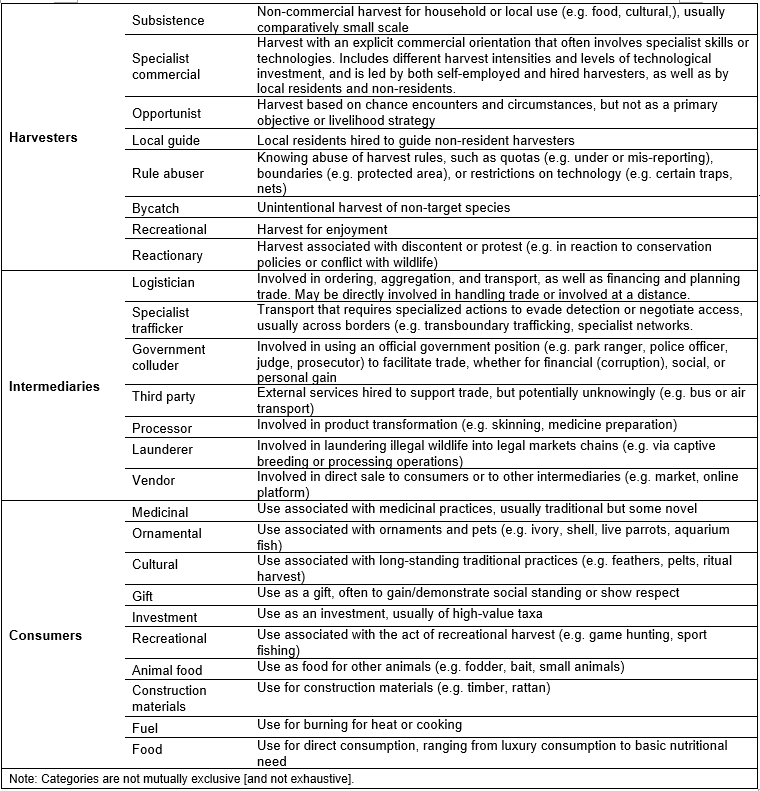

A study by Phelps et al published in 2016 separated the roles and activities involved in wildlife trafficking into three categories: harvesters, intermediaries, and consumers (see Figure 1 below). These categories are not meant to be exhaustive or mutually exclusive; they are intended to capture and illustrate the wide spectrum of actors involved in wildlife trafficking.

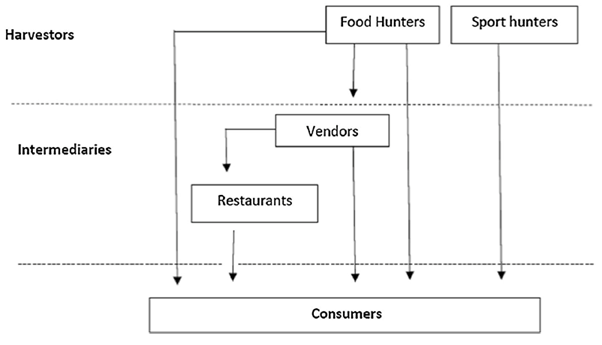

A 2018 study of bird hunting in Samoa provides insight into the categories and motivations of the people who, wittingly or unwittingly, are involved in the hunting and selling of Manumea, a protected pigeon species. Based on interviews with hunters, the study sought to distinguish between persons hunting for subsistence, for commercial purposes, and sports hunters. The study revealed some crossover between the three categories such that many subsistence hunters who hunt for family consumption also hunt for an income. Many sports hunters, most of them wealthy business owners who come from outside the area where they hunt, hunt as a hobby and for personal consumption. The study also noted that many hunters fail to distinguish the Manumea from the Lupe (another pigeon species), the intended target of a hunt, and thus end up killing Manumea by mistake. A separate category are retailers (intermediaries) who purchase meat and then sell it onwards. Two kinds of traders were identified: (1) restaurants that purchase from vendors and (2) vendors who trade to non-hunting consumers, usually by door-to-door sales rather than selling in markets. The figure below summarises the main findings. (Stirnemann et al, 2018)

Many activities in the illicit wildlife market require little skill and planning, especially if source and destination, supplier and consumer are in close proximity. After the initial act of poaching, subsequent stages often involve more organization and the involvement of local, regional and international middlemen, processing centres, et cetera. If intermediaries are required to transfer contraband from one place to another, if sophisticated methods are needed to conceal or disguise such goods, and, in particular, if international borders need to be crossed, it may become necessary for perpetrators to partner with other individuals and entities. In such circumstances, organized criminal groups may emerge in which multiple offenders collaborate and sometimes set up complex schemes to acquire, move, and sell goods illegally, to hide their activities, and to launder the proceeds of their crime.

Some of these networks are involved in trafficking multiple species. For example, on multiple occasions, ivory, rhino horn, and pangolin scales have been detected together in a single shipment. Seizures of this kind used to be uncommon; instead most recorded seizures involve shipments of a single species. It is, of course, possible for the same criminal group to move multiple commodities in separate shipments, but the fact that mixed shipments are relatively rare suggests that, as with dealers in destination markets, traffickers appear to specialize, trading in particular commodities for which they know their buyers well (UNODC, 2016).

Wildlife trafficking is a crime that is often highly organized, 'fueled by the high profits associated with specific wildlife products (e.g., ivory, rhino horn) and the ability to utilize established criminal networks and personnel, trafficking routes, and resources to entice corrupt officials' (Pires & Moreto, 2016 [s.p.]) In some instances, established organized criminal groups have become involved in wildlife trafficking to diversify their income. For example, the Irish 'Rathkele Rovers' group, known for their involvement in money laundering, drug trafficking, and theft, was caught in 2011 attempting to steal rhino horn from museums and collections in Europe and sell them in Southeast Asia (European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy, 2016; van Uhm, 2016).

There is still some debate about how extensive the involvement of organized criminal groups in wildlife trafficking actually is. While some studies point to the existence of organized criminal groups in particular stages or for specific species, others have found little or no evidence for organized crime involvement in wildlife trafficking (Pires & Moreto, 2016 [s.p.]). Depending on the species and region of the world, 'organized' can simply mean anything from three individuals who are loosely linked to a vast criminal enterprise that comprises all stages of wildlife trafficking (i.e. vertically integrated organizations) (see also the definition of 'organized criminal group' in Article 2(a) of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (see further UNODC Teaching Module Series on Organized Crime, Module 1 on Definitions of Organized Crime).

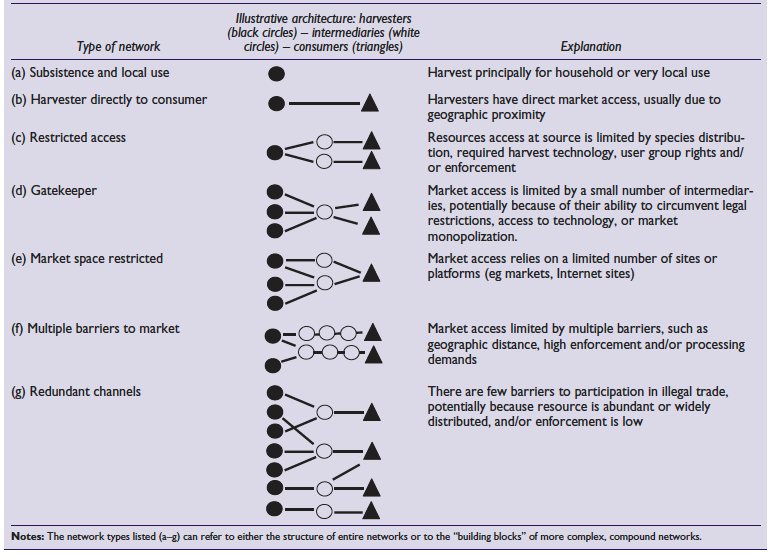

A study published in 2016 identified seven common structures in which perpetrators involved in wildlife trafficking are arranged. These structures, shown below, range from simple relationships, such as the subsistence and local use relationship, or a structure that links harvesters directly to consumers, to configurations that involve multiple intermediaries (Phelps et al, 2016).

The study further found that more complex structures are likely to arise if access to the market is restricted, whether based on the resource itself, to transport routes, or to consumers, including to distant urban or international markets willing to pay higher prices (Phelps et al, 2016). Several other reports set out various indicators, such as organization structure, sophisticated financing, the use of corruption, fraudulent documents, and violence, that, when present, may demonstrate the probability that an organized criminal group is involved (United Nations ECOSOC; EIA, 2014).

In 2006, a shipping container of used tires arrived in Douala, Cameroon, from Hong Kong. It travelled inland to an address in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, where it was emptied, loaded with timber and dispatched again for Asia.

In May of that year, Customs officers at Hong Kong's Kwai Chung terminal used an X-ray machine to examine the container and found, concealed behind the timber in a specially modified compartment, 3.9 tonnes of elephant tusks, a record seizure for Hong Kong at that time, representing at least 400 dead elephants.

Follow-up investigations found the container was intended for re-export to Macau. Hong Kong alerted the Cameroonian authorities and an inter-agency investigation was initiated in Cameroon. The Yaoundé address was traced and two further modified containers, registered to the same shipper, were discovered. The hidden compartments had been skilfully constructed and their presence suggested the traffickers had advance knowledge of the space and shipping budget for specific amounts of ivory. These containers were empty; however, ivory chippings were found inside and paperwork indicated the transport of at least 12 previous shipments along the same route. INTERPOL issued a notice in July 2006 to alert law enforcement of the method used to traffick the ivory. The shipments were linked to the 'Teng Group', a known crime syndicate connected to money laundering and drug trafficking with previous connections to Nigeria. In 1998, Customs officers in the port of Keelung, Taiwan, Province of China, seized 1.4 tonnes of ivory tusks hidden amongst a container of timber shipped from Nigeria. The consignee was a member of the Teng Group.

The group, comprising Chinese and Filipino nationals, had been operating an import/export company from Yaoundé for several years. The syndicate has been cited as making around USD 4 million every two months. In a house search, ivory carvings were recovered, along with 35 SIM cards indicating the lengths to which the suspects had gone to avoid detection. The scale of operations was extensive; subsequent DNA analysis of the ivory seized found it had originated from forest elephants, centred in south-east Gabon near the Congo-Brazzaville border. Three arrests of the Teng Group members were made in Cameroon, and attempted bribery to release an arrested suspect occurred. The suspects were charged with violations of Customs and wildlife laws and a prosecution was launched. Yet by the time the case came to court, the accused had fled and remain at large. Despite impressive inter-agency and international cooperation in both seizure and investigations, a criminal syndicate behind a series of illicit ivory shipments has so far evaded the law.

Instances of legal enterprises involved in illegal activities associated with wildlife trafficking often involve logging companies and fishing vessels. Logging companies may, for instance, operate without logging permits or illegally encroach on protected areas, harvest protected species, exceed their logging quotas, or bribe officials to unduly issue logging concessions (see, for example, van Solinge, 2016). Similarly, fishing companies or individual fishing vessels may venture unlawfully into protected areas, catch protected species, exceed set quotas, or use prohibited fishing methods.

Corporate sector involvement may also occur at the transit stage, if transportation companies knowingly or recklessly carry, import, export, or launder contraband, forge documents, or fail to comply with documentation, certification, and reporting requirements. It may also involve collusion by airline staff and crews of container or cruise ships. At the destination, corporations may play a vital part in wildlife trafficking if they deliberately or negligently source or supply timber, plants, live animals or animal products that come from protected areas, involve protected species, et cetera (see further, van Uhm, 2018).

In May 2017, a corporation based in Arizona, United States, and two of its executives were charged with conspiracy, illegal trafficking in wildlife, illegal importation, false labelling, and criminal forfeiture for trafficking sea cucumbers from Mexico.

According to the indictment, the accused contacted suppliers of sea cucumbers in Mexico and agreed to purchase approximately USD 13 million worth of sea cucumbers, knowing that these had been illegally harvested, that is, in excess of permit limits, or without a proper license or permit, or out of season. Another accused allegedly created false invoices to be submitted to US Customs officials, knowing that the sea cucumbers had been illegally harvested, sold and transported, and lacked the proper paperwork required under Mexican law.

The indictment states that after the sea cucumbers had been imported into the United States, and then sold for approximately USD 17.5 million to customers in China and elsewhere. The indictment alleges that, as part of the scheme, payments were made to bank accounts held under false names to conceal the illegal sales and hide the proceeds, and payments were also made to Mexican officials to ensure that no action was taken against the illegally harvested sea cucumbers.

In 2016, a Cape Town businessman was found guilty of defrauding the South African Revenue Service (SARS) by presenting false invoices and inflated export records of his fishing operations. He was prosecuted for over 40 charges, including racketeering, reckless business conduct, fraud and money laundering. In June 2016, he was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment.

The business man was a registered representative and vendor of a network of fishing operations. In order to receive authentic invoices for alleged expenditures of his fishing operations, he requested and accepted offers from external providers of fishing infrastructure equipment, such as refrigerators systems, fish production line and delivery trucks. Upon submitting the invoices to the SARS for VAT return, the defendant repeatedly walked away from all these agreements, causing significant financial damage to the other businesses. He successfully ran this scheme between 2005 and 2008 until his wrongdoing was discovered.

The case received wide media coverage, due to the lavish lifestyle the defendant financed with his illicit earnings and the significant ruling of the court, which included extensive imprisonment and asset confiscation.

Because fauna and flora represent high value natural resources, often under government control or regulation, they offer an important potential source of political power, and a correspondingly high risk of abuse of that power. As a consequence, corruption in the allocation of hunting concessions, in the award of licences to log, and in the issuing of permits to process, import and/or export fauna and flora is widespread.

Corruption is a complex phenomenon. (An overview of the different forms and definitions of corruption, as well as its harmful effects across the globe, is available in Module 1 of the Anti-Corruption Module Series). For the purposes of this Module, it should be noted that the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) refrains from providing one overarching definition of "corruption"; rather, it defines and classifies various forms of corruption as criminal offences, such as bribery and embezzlement (in both the public and private sectors); abuse of function (i.e. when those performing public functions misuse their power to obtain a benefit); trading in influence; illicit enrichment; and money laundering.

While UNCAC defines a number of different corrupt acts, corruption is sometimes understood in general terms as "the abuse of entrusted power for private gain", in accordance with the definition proposed by the NGO Transparency International (TI). It is clear from both the TI definition of corruption, as well as the corruption offences defined in UNCAC, that corruption occurs in the areas of wildlife and forestry.

Corruption operates either to allow wildlife trafficking to occur in the first place, or to proceed unchecked or unbalanced (Callister, 1999). Corruption can involve low-ranking game wards and forest officials who accept bribes and then 'turn a blind eye' to illegal activities (see further, Kishor & Damania, 2007). It can also reach to the top levels of government that are involved in policy decisions and law-making in the wildlife, forestry, and fisheries sectors. High-level or 'grand' corruption can be particularly damaging, as it causes significant financial losses and also encourages petty corruption at the lower levels of government (see further, Callister, 1999; Kishor & Damania, 2007). In some cases, corruption is an intrinsic part of the patronage systems that sustain the power of a country's ruling elite (FAO & ITTO, 2005). Political manipulation is a major issue in persistent illegal activities in the wildlife and forestry sectors. This often leads to a breakdown of law and order and also hampers private and foreign investment in these sectors (for further reading and teaching tools on corruption see the Module Series on Anti-Corruption).

In the context of wildlife trafficking, there are numerous ways in which bribes can be offered and paid, not only to government officials, but also to commercial enterprises and individuals who exercise control over certain areas, industries, materials, et cetera. This may involve, for example:

While most, if not all countries, have laws that criminalize corruption and bribery, these offences frequently do not constitute an adequate deterrent because they are rarely enforced, because prosecutions rarely succeed, or because penalties are low. Elsewhere, domestic offences do not capture the bribery of foreign officials. As long as the risk of being caught and sanctioned is low, and there are social norms and values that do not penalize such acts, those working in the wildlife, forestry, and fisheries sectors - in official or private capacities - corruption may thrive. For an example of tools to address corruption in these sectors, see UNODC publication " Rotten Fish - A Guide on Addressing Corruption in the Fisheries Sector".

For at least 30 years, a market-leading fishing company in South Africa executed a complicated scheme which allowed it to illegally harvest immense quantities of South African rock lobster, which were sold - with excessive profits - to East Asia, Europe and the United States of America. By paying bribes to local Fishery Control Officers, the company received fraudulent verification on their documentation, thereby covering their tracks and maintaining a veneer of legitimacy. Eventually, discrepancies between import and export records led to the company’s demise.

In 2012, the defendants were found guilty on several charges by courts in South Africa and the United States. The 14 Fishery Control Officers excepting the bribes were fined and sentenced to additional imprisonment. Similarly, the owners of the company faced significant charges and were found guilty in the United States of conspiracy to violate the Lacey Act.

There are frequent investigations and prosecutions of corruption associated with logging operations in Solomon Islands. In 2018, for instance, a former provincial premier was found guilty in the Magistrates’ Court sitting at Lata of six counts of abuse of office for accepting nearly USD 15 000 in business licence fees from a logging company and two shipping companies. (RNZ, 2018)

Other reports show that since the 1980s, the forest sector in Solomon Islands has been characterised by collusion between foreign logging companies and local politicians, systemic corruption, and poor monitoring and enforcement. A key causal factor behind this problem is the lack of alternative revenue sources for national and provincial governments, as well as for local communities. According to Transparency International, Solomon Islands faces several corruption challenges fuelled by the size of the country and its geographic spread, low state penetration of the regions and weak central institutions. In addition, it faces specific governance challenges associated with the under-resourced management of natural resources including, for example, the influence and perpetration of large-scale corruption by international logging companies.

The report continues to describe how ‘corruption among logging companies and local politicians has contributed to excessive logging, resulting in highly degraded forests that undermine the future sustainability of the sector. The logging industry is tightly connected with domestic politics, with successive governments infiltrated by logging money, and the benefits of logging largely captured by foreign companies and local politicians. These political allies of logging companies have little incentive to regulate the sector, weakening the state’s ability to defend national interests as opposed to logging interests.’