Firearms and ballistic marching play an important role in criminal investigations, as “every firearm tells a story”. The information required to depict their story can be obtained from both the exterior and interior of a firearm, or from ammunition, and can be used to further investigations and prosecutions which contribute to intelligence gathering and analysis.

Firearms and their surrounding area at a crime scene can furnish a variety of evidence. These crime scenes can include, but are not limited to any place where:

A ‘crime gun’ is a firearm that is possessed unlawfully and/or has been used in the commission of a crime. Proper examination and tracing (see below) of these items may:

Firearms-related evidence can be used both in relation to the main crime but can also lead to the building of strong parallel criminal cases, such as international firearms trafficking. Sometimes, one piece of evidence can help in both investigations. For example, a ballistic comparison can confirm that a firearm was used in a murder case but also in other crimes committed in another country, which is already an indicator of the routing of that firearm.

Too often, the value of evidence that firearms, ballistics and ammunition provide is overlooked in criminal investigations; enforcement operations stop at the point of seizure or recovery. Yet, seized and recovered firearm-related items may themselves provide critical evidence of a broad range of additional crimes, such as firearms trafficking and illicit manufacturing.

Ensuring the chronological and careful documentation of evidence relating to a crime scene, or alleged crime, is vital; this is known as the ‘chain-of-custody’. If during the investigation, steps are taken to ensure ‘traceability and continuity’ of the evidence for the duration of the investigation from crime scene to courtroom, it is possible to establish its connection to an alleged crime (UNODC, 2009). It is important to preserve the value of any evidence that is collected during an investigation. The chain-of-custody can present a significant opportunity for error if it is not maintained correctly (UNODC, 2009).

Health and safety procedures are of paramount importance when arriving at crime scenes and should remain a priority throughout the process, to ensure the safety of officers and others present. Accordingly, crime scene examinations must be undertaken with the support, guidance and supervision of suitably trained firearms and other experts, and/or forensic firearms experts, who can help ensure all activity is safe while not compromising potential forensic evidence.

Firearms identification, as detailed in Module 2, is a fundamental step in firearms trafficking investigations because it provides the essential elements for the unique identification and tracing of the firearm.

There are at least five key identifiers of a firearm: the make, model, calibre, manufacturer, and serial number. Other markings (import or proof house markings), the year of manufacture or import, as well as additional specific characteristics, may contribute to its identification.

Firearms identification can sometimes be challenging because of the large variety of firearms producers, makes and models. Sometimes, the same producer may manufacture different models of firearms with the same serial number. However, when adding the make, model and calibre to the serial number, it will be possible to uniquely identify and distinguish one firearm from another.

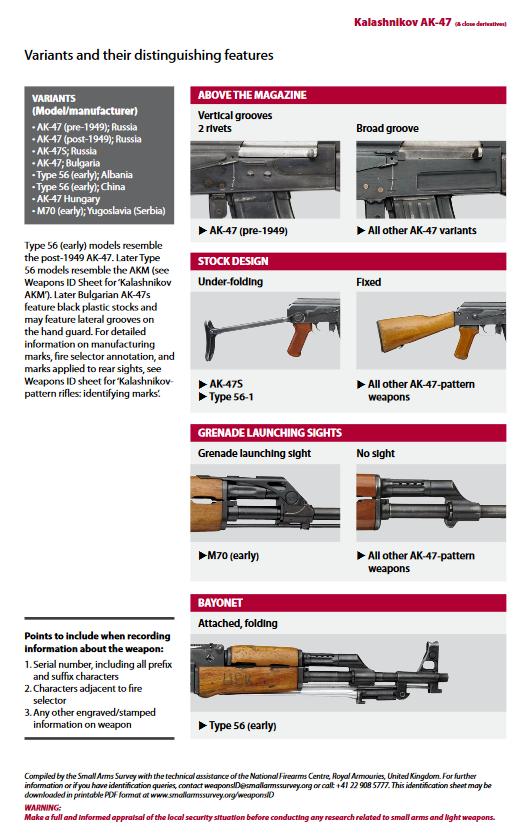

A further challenge in the identification of firearms refers to the manufacturer or make, as there are many firearms that are produced under licence by various countries. For example, the AK-47 is one of the firearms posing serious challenges to proper identification because of the similarities encountered between firearms produced by various manufacturers. It is estimated that more than 75 million AK-type firearms have been manufactured since the original AK-47 first entered service in the Soviet Union in 1949. Today, there are in excess of 30 varieties of Kalashnikov assault rifle, most retaining the distinctive banana-shaped ammunition clip, which are frequently misidentified as AK-47 rifles. Figure 8.5 shows several variants of AK-47 and some of the details that make the difference during the identification process (Small Arms Survey Weapons ID Database).

The firearms identification characteristics and tools are addressed in Module 2 on firearms.

Firearms examiners can use various tools designed to help them correctly identify a firearm, ranging from manufacturers identification tools to specialized databases. The best-known database used for firearm identification is the INTERPOL Firearms Reference Table (FRT), which is an online interactive tool used to provide a standardized methodology to identify and describe firearms (INTERPOL, 2018a).

In addition to firearm identification, the examiners need to assess the functionality of the firearm, mainly considering the following aspects:

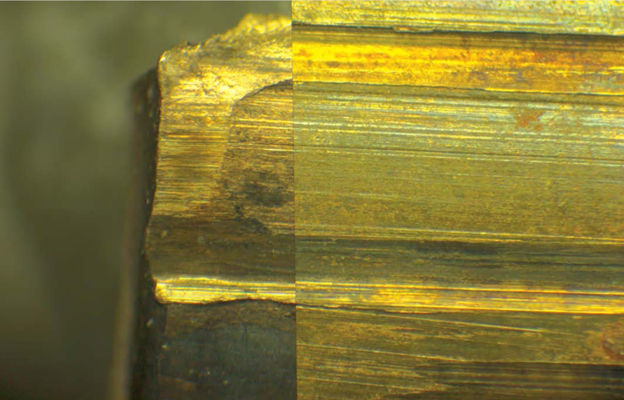

Sometimes, firearms used in crimes have the serial numbers obliterated or modified in an attempt to make tracing them very difficult, if not impossible. A firearm and tool mark examiner may perform a serial number restoration if this number has been obliterated through means such as filing, grinding, or peening.

The most used methods for serial number restoration are the magnetic particle method, chemical etching, the electrolytic method, and heat treatment.

‘Firearms tracing’ is a critical tool in the investigation of firearms-related offences, particularly those involving trafficking and distribution. It assists in identifying sources of firearms used by criminal organizations and terrorist groups, as well as providing valuable intelligence on methodologies utilized in the trafficking of these firearms. Firearms tracing can also provide evidence which may link a suspect to a firearm.

The Firearms Protocol (UNODC, 2001: 3) defines tracing as “the systematic tracking of firearms and, where possible, their parts and components and ammunition from manufacturer to purchaser for the purpose of assisting the competent authorities of States Parties in detecting, investigating and analysing illicit manufacturing and illicit trafficking.”

A successful firearms trace will identify the manufacturer and the first retail purchaser of the firearm, using the manufacturer’s records of sale. Where the firearm has been later sold by the first purchaser, tracing the weapon through the history of its distribution chain may also, subject to national laws and recordkeeping, reveal any subsequent ownership and thereby identify its current legal owner. This identified individual (or entity) may be the perpetrator of a crime or may be otherwise relevant to the case or have information to contribute about the circumstances of the crime or its perpetrator. The tracing process may thus lead to evidence that is decisive in solving or prosecuting a case.

A firearm trace is not an indication that the person of interest has committed an unlawful act; it is simply intended to provide an avenue of information for investigative fact-gathering. In many cases additional investigation will be required to determine the point when the firearm became the subject of the investigation or inquiry, or when it became illicit.

Firearm tracing is a key resource, not only for the development of leads in a criminal investigation, but also for the development of actionable intelligence on complex firearm-related crime and firearms trafficking. The mapping and analysis of national and international firearm trace data may help to:

The Modular Small-Arms-Control Implementation Compendium (MOSAIC 05.31, ‘Tracing illicit small arms and light weapons’) provides good practice and guidance on the steps for undertaking domestic and international tracing action, including the steps necessary to make and respond to international tracing requests as follows:

- became illicit while under the jurisdiction of the State that recovered it (e.g. following its domestic manufacture or import), or

- possibly entered the country by illicit means;

Firearms tracing can take place in different moments and contexts of a criminal investigation. It can be part of the initial investigative process of a law enforcement official or can also be requested by a prosecutor as part of a follow up or parallel investigation into illicit trafficking.

By implementing the tracing activities, investigators can make use of various tools available at a national level (for example, national databases on firearms owners, manufacturers, importers, and dealers) and an international level (for example, iArms and eTrace).

INTERPOL’s Illicit Arms Records and Tracing Management System (iARMS) is the only global law enforcement platform for recording international illicit firearms. It is atool for facilitating information exchange, assisting with investigative efforts and cooperating between different criminal justice agents, and it focuses on the international movement of illicit firearms, as well as licit firearms that havebeen involved in the commission of a crime (INTERPOL, 2018c).

Criminal justice agents can record data about firearms in the iARMS system and also search to see if seized weapons have been reported lost, stolen, trafficked or smuggled. This not only helps to identify where weapons have been used and have originated from but can also help to identify potential links that may occur in different parts of the world, and different trafficking/smuggling routes (INTERPOL, 2018c).

iARMS firearms tracing relies on the close cooperation of international law enforcement, and customs and border control agencies. INTERPOL has been identified as a key partner in the implementation of firearm tracing activities by the 2005 International Tracing Instrument (INTERPOL, 2018c). ‘Analysis of iARMS data and statistics has already significantly informed detailed assessments of the illicit flows of weapons to terrorist organizations, organized criminal groups and other unauthorized users’ (INTERPOL, 2018c).

Introduced in 2005, the eTrace system is a law enforcement-focused firearm tracing system operated by the United States Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) National Firearms Tracing Center (NTC). eTrace supports users in submitting, retrieving, storing, and querying firearms trace-related information. Registered users can initiate a search on virtually any data field or combination of data elements, such as firearms serial numbers, an individual’s name, type of crime, date of recovery, or other identifiers.

Consistent with the ATF mandate to prevent and fight violent crime, weapons of interest for eTrace purposes are restricted to US-manufactured and US-imported firearms that have been recovered from a crime scene. Access to the web-based service (currently available in both English and Spanish user interfaces) is limited to US and foreign government law enforcement agencies in connection with, and for use in, a criminal investigation or prosecution, and to US federal agencies for national security or intelligence purposes. Requests to the ATF to trace firearms can be submitted by any domestic or foreign law enforcement agency, although foreign agencies are required to have a Memorandum of Understanding with the ATF in order to receive this support.

Unsurprisingly, spent bullets and cartridge cases are much more likely to be found at the scene of a violent crime than the gun itself. An essential line of inquiry from this evidence is to identify the firearm, or the type of firearm, that fired them.

The science that deals with the scientific analysis of fired ammunition is called Ballistic Analysis, or simply Ballistics, which Oxford Dictionaries Online define as “the science of projectiles and firearms” or “the scientific study of the effects of being fired on a bullet, cartridge or gun.”

The UN Firearms Protocol defines “Ammunition” as “the complete round or its components, including cartridge cases, primers, propellant powder, bullets or projectiles, that are used in a firearm….” (UNODC, 2001: 2-3). A bullet is an item within a single round of ammunition.

Ballistics is divided in three subcategories:

The examination of individual and class characteristics of a spent bullet, spent cartridge or firing residues recovered from a crime scene can help classify the ammunition (make, calibre or gauge), trace the ammunition, establish the bullet trajectory, identify the shooting firearm, and establish links between the firearm and other crimes. It can also identify the shooter or establish the location of a firearm.

For example:

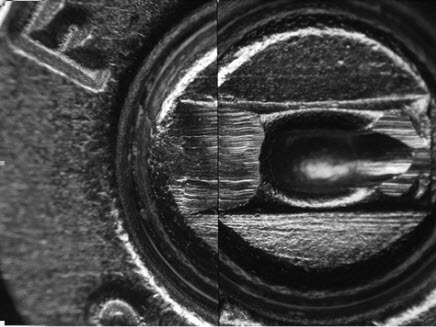

One important part of the ballistic examination is the ballistic comparison. As with fingerprints, every firearm has unique characteristics. The barrel of a weapon leaves distinct markings on a projectile. The breech mechanism also leaves distinct markings on the cartridge case. These markings are produced by the breech face itself, the firing pin, extractor, and ejector. By comparing these unique markings, the examiner can provide information that can help identify the firearm used in the shooting, whether two or more rounds were fired with the same firearms, and further connect the firearm with other crimes.

Ballistic comparison is a relatively new technology that has been developed by few companies. In technical terms, the two basic tools for ballistic investigations are the comparison microscope, which allows comparison and effective analysis of the evidence, and a software program that allows for the ballistic comparison using a system which stores the data and image base of firearms for further comparison in order to identify relationships between criminal acts.

The most well-known systems on the market are the Integrated Ballistic Identification System (IBIS), and its Ballistic Information Network (IBIN), ALIAS, ARSENAL and EVOFINDER.

In recent times, more countries have started to develop their own domestic systems, based on one of the above described major technologies (for example, SUCOBA in Colombia based on IBIS technology).

Matching ballistic information is one of the key measures in the fight against the misuse of firearms, and it has uncovered numerous connections between firearm-related crime scenes in different countries (INTERPOL, 2018b). It allows police to develop new investigative leads based on ballistics cross-comparison, and to find connections between separate crime scenes from different countries that could have otherwise remained undetected (INTERPOL, 2018b).