Discuss as a class (or in small groups) the legal, ethical and practical issues regarding the right to life, targeted killings and extraordinary rendition (examined in Modules 8 and 9).

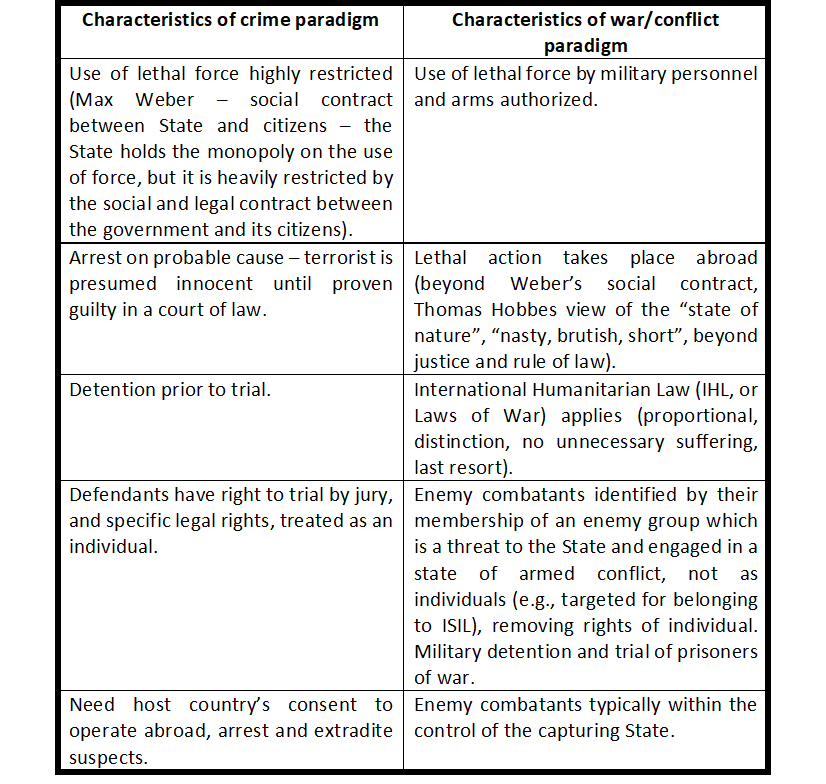

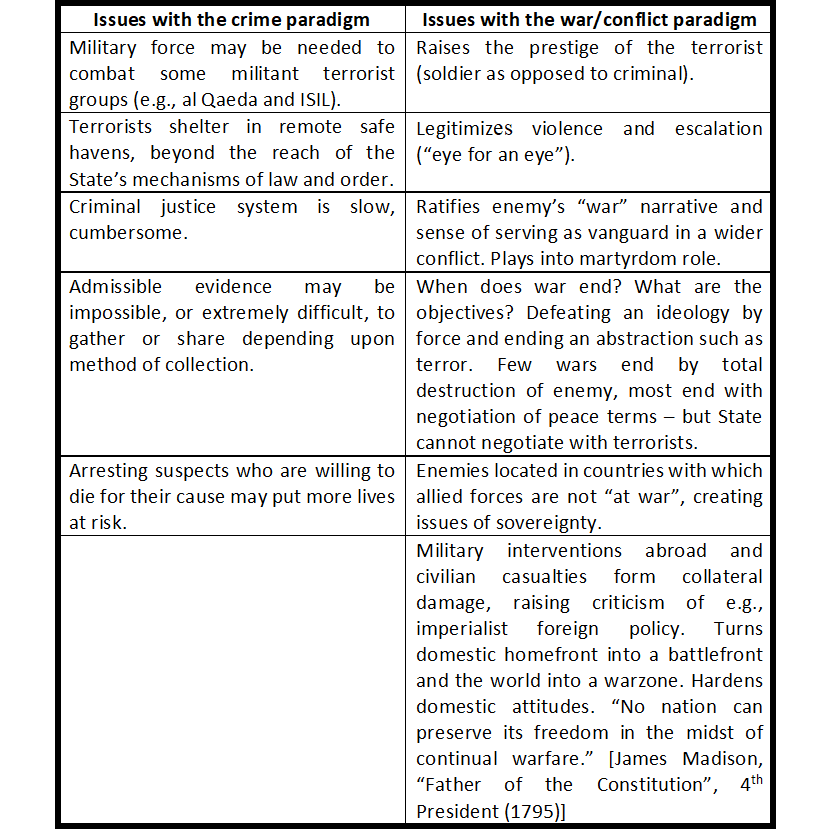

Consider the benefits and drawbacks of countering terrorism through a crime paradigm versus a war/conflict paradigm.

Explore how establishing the correct paradigm through which a State will confront terrorism – as a criminal enterprise where terrorists are to be arrested and put on trial, or as an act of war where targeted killings will be utilized - is vital in:

a) Ensuring the State has access to the necessary tools, resources, and legislation to protect itself;

b) Safeguarding against the over-extension of a State’s authority/powers, which could transgress human rights integral to healthy and functioning democracies.

The situation has been further complicated by the extent to which the activity of some well-resourced, organized and violent terrorist groups has been able to blur the lines between a war/armed conflict in a traditional sense and criminal acts of terrorism.

A primary purpose of this Module is to build upon key concepts and principles established in Modules 1-14 by going into more depth on several contemporary issues. Therefore, for students to derive the maximum learning benefit it is important that they are familiar with foundational concepts and principles of those contemporary issues topics the lecturers wish to examine. One way of achieving this is by 'flipping the classroom', in this case requiring students to do preparatory work prior to the class so that it can be assumed that they all have a basic understanding of the relevant core concepts and principles, enabling the lecturer to focus on more specialist issues.

There are many different resources which could be used for these purposes, including reading materials, videos and other tools noted in Modules 1-14 introducing the core concepts and principles upon which this Module builds which the lecturer may wish to consult. (Modules 2, 8-11, 13-14).

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) portrayed themselves as an ethno-nationalist insurgent group, fighting for an independent Tamil state, which emerged in 1976. Initially, the role of women was confined to supportive roles such as propaganda, fundraising, and recruitment. When, however, the Women's Front was created, women soon assumed a more frontline position in LTTE activities.

In a conservative society, LTTE’s membership denounced pre-existing societal norms and the LTTE’s pursuit of an independent Tamil state became increasingly synonymous with female empowerment and liberation from socio-cultural oppression. This served the strategic objective of encouraging existing female member to consolidate their dedication to the cause and also to recruit more female members.

Specifically, the LTTE’s Black Tigers suicide squad were female suicide operatives who carried out multiple attacks (and estimated 60 of the approximately 200 suicide bombings)** and who benefited from tactical advantages. A prime example is the suicide attack carried out by a young woman who assassinated Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi during his election campaign in southern India in May 1991. The LTTE exploited gender stereotypes and as attacks by women were rarely perpetrated, women gained access to high security locations otherwise inaccessible by male contemporaries.

Despite their key roles and the accompanying rhetoric of liberation and empowerment, nonetheless women did not enjoy gender equality within the LTTE which was characterized by male-dominated and patriarchal leadership. Notably too, not least in terms of social stigma, following the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka, some former female LTTE combatants have found it more difficult to re-integrate into their societies.

In this case, two Writ Petitions were filed under article 32 (writ jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Arcadia) alleging the violation of article 21 (right to life) of the Constitution of Arcadia in relation to alleged extra-judicial killings carried out by the state police and military forces in the state of Greenlandia.

The basis of claim was that over the preceding years a large number of Arcadian citizens had been killed by Greenlandian Police and members of the Arcadian army while they were in custody, which the petitioners termed ‘extra-judicial killings’. They further claimed that for a very long time the state of Greenlandia, which had been declared as a ‘disturbed area’ and had been put under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958, had subverted the civil rights of its citizens, enabling the police and armed forces to kill innocent persons with impunity even on mere suspicion of their possible involvement in terrorist/secessionist activities. Specifically, it was alleged that during the period 1985 - 2000, approximately 1,000 innocent people in Greenlandia had been killed extra-judicially.

The Counter-Affidavit, filed on behalf of the state of Greenlandia, not only denied the perpetration of extra-judicial killings, but further attempted to forestall any examination and investigation of the matter by the Court. In an attempt to justify the killings that had occurred, the state of Greenlandia contended that there were approximately 30 extremist organizations in the State whose objective it was to secede from the Republic of Arcadia and to form an independent State (i.e. nation) of Greenlandia. In pursuit of this objective, such groups had been engaged in violence against police personnel and members of the armed forces, resulting in the deaths of approximately 75 policemen and 200 members of the armed forced during the period of 1990 to 2000.

The state of Greenlandia further contended that subject to the conditions stipulated in the provisions of its national legislation, the killing of a person - such as most of the currently alleged 'victims' - by a police officer or a member of the armed forces did not amount to an offence and could be justified in law since they occurred during counter-insurgency operations in performance of lawful duties.

The Supreme Court, however, held that while the loss of lives of the policemen and members of armed forces represented a grievous loss, the state of Greenlandia was not entitled to cite this as grounds to justify custodial deaths, 'fake encounters' killings or what the Court termed as 'administrative liquidation'. This simply was not permitted by the Constitution of Arcadia. In a situation where the Court found a person’s rights, especially the right to life, under assault by the State or the agencies of the State, it was obliged to step in and stand with the individual and prohibit the State or its agencies from violating the rights guaranteed under the Constitution.

Finally, the Supreme Court appointed a High-Powered Inquiry Commission to investigate the allegations of extra-judicial killings.

On 13 September 2011, the Basque weekly Ekaitza, published a cartoon representing the attack on the twin towers of the World Trade Center, with the caption: “We have all dreamt of it . . . Hamas did it” (the text is a parody on an advertisement slogan well known at the time). Mr. Leroy was the cartoonist who had drawn and submitted the cartoon. In its next issue, the magazine published excerpts from letters and emails reacting to it. It also published a statement by Leroy explaining that, when making the cartoon, he had intended to express his anti-American feelings, but had failed to consider the human grief and suffering caused by the attacks. The public prosecutor initiated criminal proceedings against the editor of Ekaitza on charges of condoning terrorism and against Mr. Leroy on charges of complicity in condoning terrorism under the French Press Act. Both were found guilty and sentenced to the payment of moderate fines.

Mr. Leroy applied to the ECtHR alleging a violation of his freedom of expression. The ECtHR found that the measures taken against Mr. Leroy were based on law and pursued a legitimate aim. As to the proportionality of the interference with his freedom of expression, the ECtHR considered that through the drawing and the text accompanying it, Mr. Leroy had expressed his support and moral solidarity with the authors of an attack that killed thousands of civilians. He had offended the dignity of the victims. The ECtHR accepted that Mr. Leroy’s cartoon could be considered satire, but it nonetheless insisted that there are “duties and responsibilities” coming with the exercise of freedom of expression. The ECtHR decided that the penalty had not been disproportionate. There was no violation of the right to freedom of expression.

A particular practice of note here has been the abduction of women and girls (some as young as nine years of age), and their subjection to sexual slavery. Many were subjected to rape by their ‘fighter-owners’ and frequently severely beaten. In 2016, it was estimated that 3,200 Yazidi women and children were still being held by the Islamic State. Those women and children who escaped or were bought back by their families’ report suffering from serious physical and mental trauma; many experience suicidal thoughts.

"We were registered. ISIS took our names, ages, where we came from and whether we were married or not. After that, ISIS fighters would come to select girls to go with them. The youngest girl I saw them take was about 9 years old. One girl told me that ‘if they try to take you, it is better that you kill yourself’."

Girl, aged 12 at capture, held for seven months, sold four times.

The practice of abduction and sexual slavery is not confined to the Islamic State, but has also been perpetrated by Boko Haram in Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger. Since 2009, the group has subjected many women and girls to widespread and severe forms of abuse, including sexual slavery, which has resulted in many becoming pregnant.

In addition, these women and children have been subjected to other serious human rights violations, such as being beaten repeatedly if unable or unwilling to adopt the group's religious beliefs; or being deprived of basic essentials such as food and water, or even stoned to death.

One high profile case was the abduction of 276 school girls from Chibok, Borno State, on 14 April 2014. Some, but not all of the girls, managed to escape or were rescued. All of them reported cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, sexual violence and other forms of abuses.

The abduction resulted in a global media campaign calling for the girls' release and return, 'Bring back our girls’.***