Many, perhaps the majority of NGOs, include awareness-raising and community economic development activities as part of their efforts to prevent trafficking in persons. A substantial number provide support and assistance to help protect victims. A smaller number of NGOs assist law enforcement agencies in the investigation and prosecution of trafficking cases by providing information and evidence on suspected trafficking activities in the communities in which they are working. They may also provide legal assistance to victims.

NGOs working in developing communities can contribute in the following ways:

Advocacy networks between NGOs can also be important, with different organizations working together to fill gaps in governmental responses to trafficking in persons (Noyori-Corbett and Moxley 2018, p. 955). Rousseau (2018, p. 7) argues that, for some areas, NGOs can be more effective and have a more positive impact than State agencies. For example, given that NGOs are less focused on criminal justice efforts, they are better placed "to provide grassroots interventions that empower survivors and facilitate their long-term reintegration. Civil society can use its close interactions with the individuals and communities affected by human trafficking to develop innovative reintegration models that place victim empowerment at the core of the aftercare system".

In a worldwide study of 1,861 anti-trafficking NGOs, Limoncelli (2016) made a number of interesting findings. Of particular note was that the overwhelming focus of NGOs was on sex trafficking, with many focused on child sex trafficking. In comparison, very few NGOs worked on forced begging, child soldiers or trafficking for adoption. In terms of the activities conducted by the surveyed NGOs, the majority focused on education efforts and awareness-raising, following by legal and policy advocacy. Less than a third of NGOs provided services to victims or were engaged in rescue efforts.

Box 5 provides some illustrative examples of the ways in which NGOs have contributed to anti-trafficking efforts.

In Czechia, the Ministry of Interior set up a special programme on support and protection of victims of trafficking older than 18 years. The objective of the programme is to provide probable victims with support and protection based on an individual risk assessment and to enable access to the programme of witness protection. The programme also protects potential victims of THB who are witnesses in a trial and who cooperate with law enforcement authorities. If a potential victim voluntarily accepts an offer to participate in the programme he/she fills in and signs an initial statement which encompasses the rights and duties relating to his/her involvement in the programme. The victims are provided with accommodation, psychosocial services, legal services, vocational training etc. As an integral part of the programme, the victims are granted a 60-day reflection period during which they can decide whether or not they want to come into contact with law enforcement agencies. A system of voluntary return for third-country nationals and EU citizens who are victims of trafficking in persons in the Czech Republic and Czech citizens identified abroad respectively is also included in the programme.

Participants

Specialized NGOs or the police can nominate people for placement in the programme, after which the Ministry of the Interior is consulted as the provider of the programme.

What makes this practice successful

All the victims enrolled in the program for the year 2014 gave consent to provide the police with evidence concerning their cases. NGOs can thus make an important contribution to the willingness of victims to cooperate with the police. The NGOs motivate the victims during their reflection period by providing them with information about their rights as well as obligations that arise from being in the position of witness in a trial.

NGOs can contribute to and assist the work of law enforcement agencies in investigating suspected cases of trafficking in persons, rescuing victims and arresting and prosecuting traffickers. Often, collaboration between NGOs and law enforcement occurs at meetings of multi-disciplinary teams of comprised of government agencies and NGO representatives. These meetings aim to coordinate the gathering of intelligence, investigation of suspected trafficking situations, planning and execution of arrest and rescue operations and the protection and care of victims.

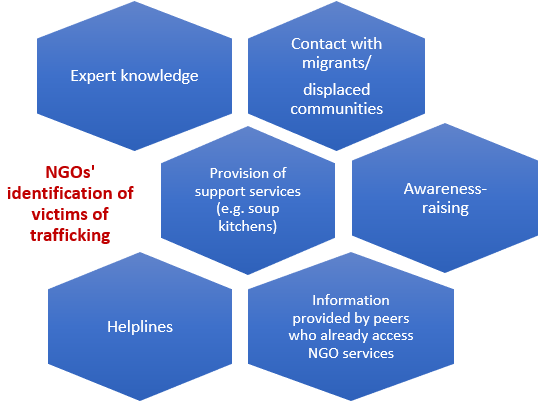

In particular, some NGOs are uniquely placed to receive such intelligence on trafficking in persons. This may be:

Figure 1 provides an overview of contributions NGOs are making in identifying potential victims of trafficking, in the course of carrying out their other activities.

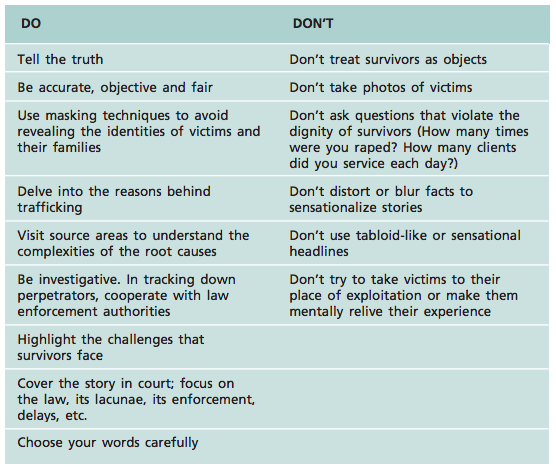

One important issue for States and NGOs operating collaboratively is the separation of roles between the two. Where should the line be drawn? There are safety and security issues for both NGO staff and victims. There are several codes of conduct providing helpful guidelines to NGOs as to what they should and should not do. For example:

The example in Box 7 describes an instance where the actions of an NGO had a negative effect on the rights and welfare of children.

The authorities in many countries now insist that children leaving their own country who are below a minimum age (such as 15 or even 18) should carry a letter signed by one or both parents giving their formal permission for the child to leave the country. This is more likely to prevent children being taken abroad by one of their own parents, following separation or divorce, than to stop traffickers taking them across a frontier, due to the various ruses which traffickers use.

Border formalities give immigration officials various opportunities for protection, for example to record which children are entering a country in circumstances which, even vaguely, suggest they may be exploited subsequently and to arrange for them to receive a subsequent visit from a social worker to check on their welfare. However, interceptions can easily become abusive if children who are not being trafficked are refused permission to proceed with their journey.

For example, in Nepal non-governmental organisations have been allowed by the authorities to set up check-points on roads crossing the border to India. They employ specialists known as 'physionomists' who are reputed (in Nepal) to be able to identify adolescent girls who are being trafficked. In effect the NGOs concerned have given themselves police powers to stop adolescent girls from crossing to India, transferring the girls instead to their own NGO transit centres, where some are kept, often against their will. The 'physionomists' appear to use criteria based on caste and social class to identify adolescent girls who belong to social groups where a disproportionately high number of girls have been trafficked in the past. Many of the 'physionomists' reportedly come from such groups and act in good faith under orders from the NGOs employing them.

The girls who are detained in transit and 'rehabilitation' centres view the NGO as a powerful institution which is in league with the authorities and whose power they cannot contest. In the worst cases, intercepted girls who have attended residential training courses given by NGOs have been stigmatised on their return home, because the NGO is known to be involved in anti-prostitution activities and the girl is consequently suspected (unjustifiably) of having been involved in prostitution. Such interceptions are reported to have diminished as the number of children fleeing from political violence has increased. Interception on the basis of little specific evidence that the child concerned is in danger of harm can be justified if the child concerned has not yet reached puberty and is palpably too young to be travelling alone. However, the same does not apply to adolescent boys or girls. In the case of adolescents, it might be justified if there is substantial evidence that the vast majority of adolescents crossing a border are being trafficked-such a large proportion that it is reasonable to make the presumption that most adolescents crossing the border are destined for exploitation. However, in the case of Nepal, NGOs made this assumption without obtaining adequate evidence. It was not until 2005 that an international NGO commissioned research into the reasons why young people crossed the border and concluded that there were numerous good reasons. Furthermore, interceptions are acceptable when carried out by law enforcement officials such as the police or immigration officials. The involvement of NGOs in stopping adolescents or young adults from exercising their freedom of movement is an abuse of power, as well as of human rights.

While NGOs are a useful and often integral part of a response to trafficking in persons, their involvement can also have negative impacts in some cases. De Shalit, Heynen, and van der Meulen (2014) argue that NGOs have a tendency to focus on particular types of trafficking, particularly sex trafficking, thus potentially obscuring proper and holistic understandings of the crime. The competition for funding that often drives the policies, practice and organization of NGOs can also undermine the efficacy of their anti-trafficking efforts (see, for example, Foerster 2009).

The media can have substantial effects on how the public perceives and understands trafficking in persons (Houston-Kolnik, Soibatian, and Shattell 2017, p. 5). Media coverage of trafficking generally reflects governmental and law enforcement views on the crime (Gulati 2011). The media can play a valuable role (as mentioned in Modules 4, 5 and 7 of the Teaching Module Series on Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants as well as in Module 10 on Media Integrity and Ethics of the Module Series on Integrity and Ethics), including in:

However, this must be done in an informed and responsible manner. For example:

A number of studies have found that media representations of trafficking and victims of trafficking can have deleterious consequences, failing to acknowledge the "complexities of human trafficking or the multiple forms of trafficking, shaping uneducated responses to trafficking or contribute to disempowering views of survivors as victims" (Houston-Kolnik, Soibatian, and Shattell 2017, p. 5). A study of the media in Slovenia by Pajnik (2010), for example, found that media representations overwhelmingly presented trafficking as solely concerned with prostitution and sexual exploitation.

If the media has the opportunity to directly interact with trafficked persons, it must do so in a sensitive manner that does not cause secondary victimization (see, for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on interviewing trafficked women). Their informed consent must be obtained, preferably in writing. For child victims, consent must be obtained from parents or guardians. To this end, training is essential. The State must take the appropriate measures to guarantee the rights and protection of victims, while respecting freedom of expression and freedom of the press. Consequently, journalists, publications and media channels who do not comply with the requisite standards must be accountable.

As shown in Figure 2, the following guidelines published by UNODC are applicable:

UNESCO has developed the following methodology for producing radio programmes in minority languages to educate target audiences on issues of HIV/AIDS, drugs and human trafficking.

An example of the awareness-raising work of UNESCO using this methodology is the drama "Life of tragedies", written in the Jingpo language, which won first prize at the fifth Provincial Literary and Artistic Creation Awards held in Yunnan, China. This radio drama was written by a renowned Jingpo author, Yue Jian. Financial support for this program was provided to UNESCO by the Asian Development Bank. "Life of tragedies" was both broadcast on radio and distributed on cassette and CD. Another radio drama "The sight of the snow mountain", in the Naxi language, addresses the issues of HIV/AIDS and human trafficking. In conjunction with its radio program work, UNESCO (in cooperation with the New Life Centre Foundation in Chiang Mai, Thailand) has also produced an album of popular Lahu songs addressing issues of HIV/AIDS and human trafficking, sung by Lahu singers popular in Thailand and Myanmar.

In order to warn potential migrant workers about recruitment under false pretences for work that was too good to be true, the Slovak Republic ran a campaign on Facebook. The campaign consisted of several phases. The first phase included the launch of a fake page of a fake recruitment agency offering a great job abroad and a good salary (www.superzarobok.sk). The campaign on Facebook targeted young people from areas of Slovakia affected by unemployment and a higher rate of victims of trafficking in persons. The fake page showed several significant signs of a fake page. After logging in on the fake page, the person concerned was asked to fill out a registration form to get a great job. One of the requirements was to include their own email address and an email address of a close person or relative. After a few days an email was delivered to the addresses provided in the registration form saying that the person might have become a victim of trafficking in persons. The email also contained a link to the educational webpage ( www.novodobiotroci.sk - available only in Slovak) where all useful information on trafficking and job search could be found in a very understandable form.

The video with English subtitles can be accessed here.

Partners involved in the cooperation and their roles: The Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic and Civil Society Organisation "Brániť sa oplatí" cooperated in the preparation of the fake page and the educational website. The cooperation with Facebook was performed by the NGO.

What makes this practice successful: The advertisement for the offer of the fake page was massively displayed: 700,000 people saw the advertisement and 40,000 people saw the campaign. 2,300 people used the form to register and 7,000 people visited the information webpage during the campaign.

Academic and research institutions play a role in educating society, disseminating knowledge, critically analysing current anti-trafficking initiatives and driving debate and research. This is recognized in the Doha Declaration as well as in other instruments, as listed below. Importantly, most academic institutions are independent of governments, meaning that research produced is more likely to be free of political biases or concerns.

The Council of Europe Convention provides as follows:

Article 5(2): "Each Party shall establish and/or strengthen effective policies and programmes to prevent trafficking in human beings, by such means as: research, information, awareness raising and education campaigns, social and economic initiatives and training programmes, in particular for persons vulnerable to trafficking and for professionals concerned with trafficking in human beings".

Article 6: "To discourage the demand that fosters all forms of exploitation of persons, especially women and children, that leads to trafficking, each Party shall adopt or strengthen legislative, administrative, educational, social, cultural or other measures including: (a) research on best practices, methods and strategies".

Furthermore, article 18(2) of the Directive 2011/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Protecting its Victims states:

"Member States shall take appropriate action, including through the Internet, such as information and awareness- raising campaigns, research and education programs, where appropriate in cooperation with relevant civil society organizations and other stakeholders, aimed at raising awareness and reducing the risk of people, especially children, becoming victims of trafficking in human beings".

Similarly, the Brussels Declaration on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings, which was adopted in November 2002, states:

"Closer links should be developed with educators and Ministries of Education with a view to elaborating and including relevant and realistic teaching modules in school and college curricula and to informing pupils and students of human rights and gender issues.

These subjects should specifically be linked to teaching young people about the dangers presented by trafficking crimes, the opportunities for legal migration and foreign employment and of the grave risks involved in irregular migration."

By way of a domestic example - emphasizing the importance of research - in 2003, the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act was amended through the addition of section 112A, which refers to the importance of "carry[ing] out research, which (…) provides data to address the problems identified … Such research initiatives shall, to the maximum extent practicable, include:

In 2005, Section 112A was expanded to include references to:

In 2008, this Section was again amended to read as follows:

"An effective mechanism for quantifying the number of victims of trafficking on a national, regional, and international basis, which shall include, not later than 2 years after the date of the enactment of the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, the establishment and maintenance of an integrated database within the Human Smuggling and Trafficking Centre."

The study of trafficking in persons should not be limited to law courses at universities. Rather, it is pertinent to many other disciplines and should be integrated into applicable courses or learning, including, where appropriate, anthropology, criminal justice, education, history, international relations, political sciences, psychology, public health, social work, sociology, women and gender studies.

Religious institutions may have an important role in supporting comprehensive strategies to combat trafficking in persons. The extent and importance of their contribution will depend on the prominence and role of religion in a particular society. First and foremost, a substantial number of NGOs operating in the anti-trafficking sector are faith-based.

In some countries in the Middle East, the practice of the so-called "sponsorship rule" can render the sponsored worker vulnerable to exploitation and situations of trafficking. Sheikh Youssef el Qaradawi, an eminent Islamic scholar, issued a fatwa (an Islamic legal opinion) in March 2008 that the sponsorship rule that prevails in some countries is inconsistent with the teachings of Islam and should be abolished: "[t]he sponsorship system nowadays produced a visa market, leaving tens of workers living in sub-human conditions as a large number of labourers are accommodated in small areas. It is really a shame and also it is against the Islamic principles which call for respecting human rights" (John Hopkins, School of Advanced International Studies and others, 2013).

How faith-based groups can work together with secular ones to combat human trafficking

How happily can groups motivated by faith co-operate with secular ones to achieve a common goal or defeat a common enemy? On the face of things, this should work best when the foe (be it a disease or a social problem) is so manifestly bad that everybody wants to thwart it. One such enemy, you might think, is human trafficking, especially of minors. But Richard Flory, research director at the University of Southern California's Centre for Religion and Civic Culture, told me that global religious bodies, operating in poor countries, sometimes get the problem of trafficking wrong. By concentrating on rescuing individuals, they fail, in his view, to grasp the social and economic forces that drive people into prostitution.

On the other hand, successful examples of secular-religious co-operation certainly exist. I asked Sara Pomeroy what prompted her to start a small NGO that campaigns against human trafficking in the American state of Virginia, and she cited the Book of Isaiah, especially chapter 61 in which the prophet proclaims that he was sent by the Lord to "bind up the broken-hearted, to proclaim freedom for the captives and release from darkness the prisoners..."

But the daily work of her organisation, the Richmond Justice Initiative, is thoroughly hard-headed and practical. It includes warning youngsters about the risk posed by sex-traders who prey on the dreams and frustrations of vulnerable teenagers, often using social media. It also involves a relentless struggle, in coalition with other NGOs, to tighten up the state's laws. Despite some hard-fought legislative changes in 2011, Virginia is still rated poorly by national NGOs which monitor the performance of states in the fight against trafficking. Performance, in this case, means having laws that punish traffickers ruthlessly and treat people who are trafficked, especially minors, as victims rather than wrongdoers. Only a few weeks ago the law in Virginia changed to make it easier to investigate trafficking rings operating in more than one county.

Calling herself a non-denominational Christian, Ms Pomeroy told me she collaborates happily in this cause with Roman Catholics, Baptists, Methodists and Pentecostalists, as well as with purely secular NGOs. But in her own NGO, it is a principle that "we don't do anything without prayer, because we are fighting against something which is very evil."

At the micro-level where her group functions, co-operation between all the parties that sincerely want to stop trafficking (secular and faith-based campaigners and government authorities) seems to work quite well. Voluntary groups, whatever their inspiration, are able to engage with the human realities of trafficking in a way that government agencies, often hamstrung by bad laws, cannot easily do. That can lead to some helpful synergy.

But when government authorities and religious bodies try to pool their efforts at a much higher level, the results seem rather modest. Last week the President's Advisory Council on Faith-Based and Neighbourhood Partnerships (FBNP) delivered some recommendations on how to combat "modern-day slavery"-which has become a catch-all term for sex-trafficking (whether or not it involves moving people) and all forms of bonded or indentured labour. The council's members include some of America's most senior religious figures, mostly of a liberal stripe. One of its jobs is to provide input for the Office of FBNP, a standing body that as I posted recently has just acquired a high-powered new boss. Council members include Katharine Jefferts Schori, presiding bishop of America's Episcopal Church which is at odds with conservative parts of the Anglican Communion, and Sister Marlene Weisenbeck, a past president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious which has a long-running dispute with the Vatican. (This week the habit-less American nuns received a formal rebuke for "radical feminism" mingled with appreciation of their humanitarian work.)

Despite the intellectual armoury at its disposal, the council's policy document seems rather vague. It proposes upgrading the federal agencies that deal with trafficking, including the State Department office that tracks the problem, and it urges the administration to avoid abetting "slave labour" in its own procurement of goods and services. Perhaps the toughest statements in the document are that "survivors of modern-day slavery should never be treated as criminals" and that the law should be changed to ensure that "victims are not imprisoned or otherwise penalised for the crimes committed by their traffickers."

There is little sign in the document of any particular moral or metaphysical sensibilities that faith-based bodies might bring to the issue of trafficking. Perhaps that is inevitable given the context: reporting to an administration which sees huge downsides and not much upside in anything that tinkers with the relationship between church and state. In an e-mail exchange, I asked Sister Weisenbeck about the division of labour between faith-based and secular groups in the fight against trafficking. Her answer implies that some tasks in this common struggle, against a foe whose ghastliness was universally recognised, are best left to secular brethren.

Faith-based organisations will become advocates, educators, and justice seekers specifically because of the moral convictions of their faith concerning the dignity of persons. Many NGOs are faith-based...[but] those that are not may be especially helpful when the tenets of separation of church and state could be problematic in the exercise of certain activities. Assuming that secular NGOs function on humanitarian values, I doubt if there is anything in [our] report that any NGO with a well-formed conscience would not have written. Human slavery in any form is heinously reprehensible.