SOM is defined in Article 3 of the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants):

(…) the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident.

The smuggling of migrants refers to the facilitation of unauthorized entry and/or the stay in one country, and its related activities (such as procurement of fraudulent documents). In addition, to be characterized as a smuggling offence, requires the intent of gaining financial or material benefits as the result of procuring the irregular entry (or stay) into a country. In other words, a person who facilitates the entry into a country through irregular means of another person (or other persons) exclusively on the basis of family ties or for humanitarian reasons, and not for the purpose of generating a profit, would not fall under the scope of the Protocol (See a full discussion of the definition of SOM in Module 1).

Trafficking in persons is defined in Article 3 of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Protocol against Trafficking in Persons).

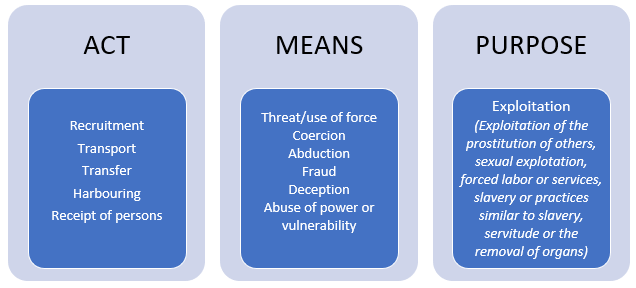

(a) "Trafficking in persons" shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs;

(b) The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) have been used;

(c) The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered "trafficking in persons" even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article;

(d) "Child" shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.

To be qualified as TIP, three elements must be present: the act (e.g. recruitment, transportation, harbouring a person), certain means and the purpose: exploitation. The consent of the adult victim is deemed irrelevant when the means listed in the Protocol are used (e.g. threat or use of force, other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or of a position of authority). In the case of children, there is no such requirement, as it is considered that children cannot give their consent given their particularly vulnerable status (See UNODC Toolkit to Combat TIP, 2008). The list of possible forms of exploitation is not meant to be exhaustive (see Module 6).

The element of exploitation alone is not sufficient to be considered as a situation of trafficking, according to the Protocol's definition. There must be elements of coercion or deception or one of the other means listed in the definition. A person may be deceived on the type of work that she/he is expected to perform, the working conditions and arrangements (pay, number of working hours) as well as the living conditions (if the employer provides for accommodation and food) - see Module 1.

Although TIP and SOM are distinct crimes, they have historically been and still are frequently confused or conflated, given their common interconnections with the irregular crossing of international borders. However, in the case of TIP, there is no requirement of crossing a border, and thus TIP can occur within one country, as well as in the context of migration through legal means.

Besides, trafficking involves the intent to exploit and the use of coercion and/or deception in achieving the exploitation purposes. In the case of smuggling - meaning migrants who use the help or service of smugglers (or also called facilitators of irregular migration) - the service-transaction stops theoretically once the service is provided. However, it is important to remember that the use of violence and human rights violations can occur in the context of SOM, while not being part of the definition of the offence (SOM offence recognizes aggravating circumstances of the crime) - see Modules 2 and 11.

The Protocol against TIP includes in its very name the mention 'especially Women and Children', which means that special attention should be dedicated to these groups that are considered disproportionally affected by the crime of TIP. This special consideration reflects the way trafficking has been understood historically, as being primarily a women issues, an element that is discussed below.

Historically, Trafficking in Persons (TIP) has been largely framed as a women-centered issue, with a strong association, even conflation, with forced prostitution and sexual exploitation. The ways in which trafficking in persons are understood today are still marked by the way it was originally viewed. Indeed, there are legacies of the way trafficking was initially defined. A quick look at the various international legal instruments that have followed one another since 1904 suffices to show that the first concern regarding trafficking, back then using the term 'white slave traffic', was prostitution (sex work).

1904: International Agreement for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic, signed in Paris

1910: International Convention for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic, signed in Paris

1921: International Convention for the Suppression of Traffic in Women and Children, League of Nations

1933: International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women of Full Age, League of Nations

1949: Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others, Approved by the UN General Assembly.

At the end of the 19 th century, growing concerns emerged that women, primarily 'white' women were being traded and forced into prostitution (sex work). That is when the term 'white slave traffic' came about. It referred to the 'alleged' traffic for forced prostitution of white Caucasian women, internally between cities, or across borders. It gave rise to important anti-white slave campaigns, principally in England but also in other Western countries such as the United States. As pointed out by scholars (such as Walkowitz 1992 in England, and Donovan in the United States), these campaigns were based on narratives of sexual danger and were racialized: the victims were 'white' Caucasian women, and the perpetrators were mostly believed to be foreigners (Walkowitz, 1992). This anti-white slave movement led to the adoption of a series of international instruments (see box 5). It was not until the first United Nations Convention on TIP addressed the issue in 1949 that the scope of the definition was broadened and was no longer exclusively female-oriented. Yet, in this 1949 Convention, trafficking was still equated with the exploitation of prostitution of others. For a discussion on the legacies of the anti-white slave movement in the anti-trafficking movement of today see Laura Lammasniemi 2017, also discussed in Module 15 "Gender and Organized Crime" of the Teaching Module Series on Organized Crime.

In the Protocol against TIP, all persons are included (men, women, children) and distinct types of exploitation are taken into consideration, not only sexual exploitation. However, it is relevant to highlight that the specific attention to women and children has remained a concern over time, as reflected in the title of the Protocol giving mention to " especially women and children".

Still today, despite a progressive shift towards greater attention to other types of trafficking, such as for forced labour in different labour sectors, there is still a strong focus on TIP for sexual exploitation. Indeed, the way trafficking is portrayed and understood in mainstream public representations is still often associated with sexual exploitation and forced prostitution of women and girls (see section on key debates in the critical scholarship on TIP and SOM for a discussion on the terminology between prostitution and sex work).

The strong women-centric view on TIP is also reflected by the fact that trafficking in persons is mostly considered a form of violence against women and girls. Since the 1970s, several international documents and statements bring TIP within the scope of violence against women:

More recently, the elimination of TIP has been included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the SDG 5.2, trafficking is included as one of the forms of violence against women and girls:

SDG 5.2 calls for the "elimination of all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation".

More broadly, achieving gender equality is one of the leading goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It is a cross-cutting and comprehensive goal that is central to the achievement of the 17 SDGs, including the goal that relates to the violence against women and girls. Achieving equality between women and men ( de jure and de facto ) is a key element in the prevention of violence against women (including trafficking).

To sum up, the way trafficking has been integrated and addressed in international instruments (and statements) shows that it has generally been viewed and constructed as being first and foremost a type of violence against women (and children).

Before discussing the global overview on TIP, it is important to understand what some of the root causes are. The term 'root causes' is often used to refer to the multi-level factors that may be conducive to increased vulnerability or risks to exploitation, including trafficking situations. Equally, the same root causes are at the origin of the motivations for people to migrate and to undertake hazardous, perilous and at-risk/unsafe migration journeys.

Gender inequality: Gendered poverty, lack of viable employment opportunities, lack of control over financial resources and limited access to education are all factors that can exacerbate the vulnerability of women and girls to trafficking.

Gender-based violence: Gender-based violence and cultural norms that normalize such violence contribute to the cycle of violence against women and girls and make them more vulnerable to trafficking.

Discriminatory labour or migration laws and gender-blind policies: Labour and migration laws that lack a human rights and gender-sensitive approach may restrict women's ability to move freely and change employment, which increases the likelihood that women will seek employment in unregulated and informal sectors. This subsequently increases women's vulnerability to trafficking and exploitation.

Conflict, post-conflict settings and humanitarian crises: In the absence of the rule of law during crises, women and girls can become highly vulnerable to different forms of exploitation. This is due, for example, to the fact that women and girls can be targeted by armed groups for sexual slavery, domestic servitude and forced and child marriages.

Globalization and its effects in terms of global inequalities across countries, and within countries, of unequal access to decent work and resources and opportunities, also form part of the global root causes.

TIP disproportionally affects people whose rights may already be compromised, including other groups than women and girls. The root causes enumerated in Box 8 focus on women and girls. However, men and boys as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) persons will also face, yet differently, inequalities, discriminatory labour and migration laws and structural (economic, political and social) power imbalances.

For example, LGBTI individuals may experience discrimination, stigmatization, persecution and rejection (social/family) on the grounds of their sexual orientation or gender identities. As a result, they may be confronted with social isolation and/or weaker social and family networks, discrimination and unfair treatment at the workplace, which in turn might increase their risk of exploitation. In relation to work, people can be fired or refused to be hired based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. For more information about the work being done by the Independent Expert on the protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI), see United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR).

It is proposed that lecturers discuss with students how to, by using an intersectionality approach, identify the root causes to trafficking in their country and region, by being attentive to include all persons (see Exercises).