Computer-related offences include cyber-enabled crimes committed "for personal or financial gain or harm" (UNODC, 2013, p. 16). The cybercrimes included under this category "focus … on acts for which the use of a computer system [or digital device] is inherent to the modus operandi" of the criminal (UNODC, 2013, p. 17). The 2013 UNODC Draft Comprehensive Study on Cybercrime identified the following cybercrimes in this broad category (p. 16):

Under the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention, fraud and forgery are considered part of the computer-related offences (i.e., computer-related forgery and computer-related fraud). Article 7 of the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention defines computer-related forgery as "intentional… and without right, the input, alteration, deletion, or suppression of computer data, resulting in inauthentic data with the intent that it be considered or acted upon for legal purposes as if it were authentic, regardless whether or not the data is directly readable and intelligible." This cybercrime is also prohibited under Article 10 of the Arab Convention on Combating Information Technology Offences.

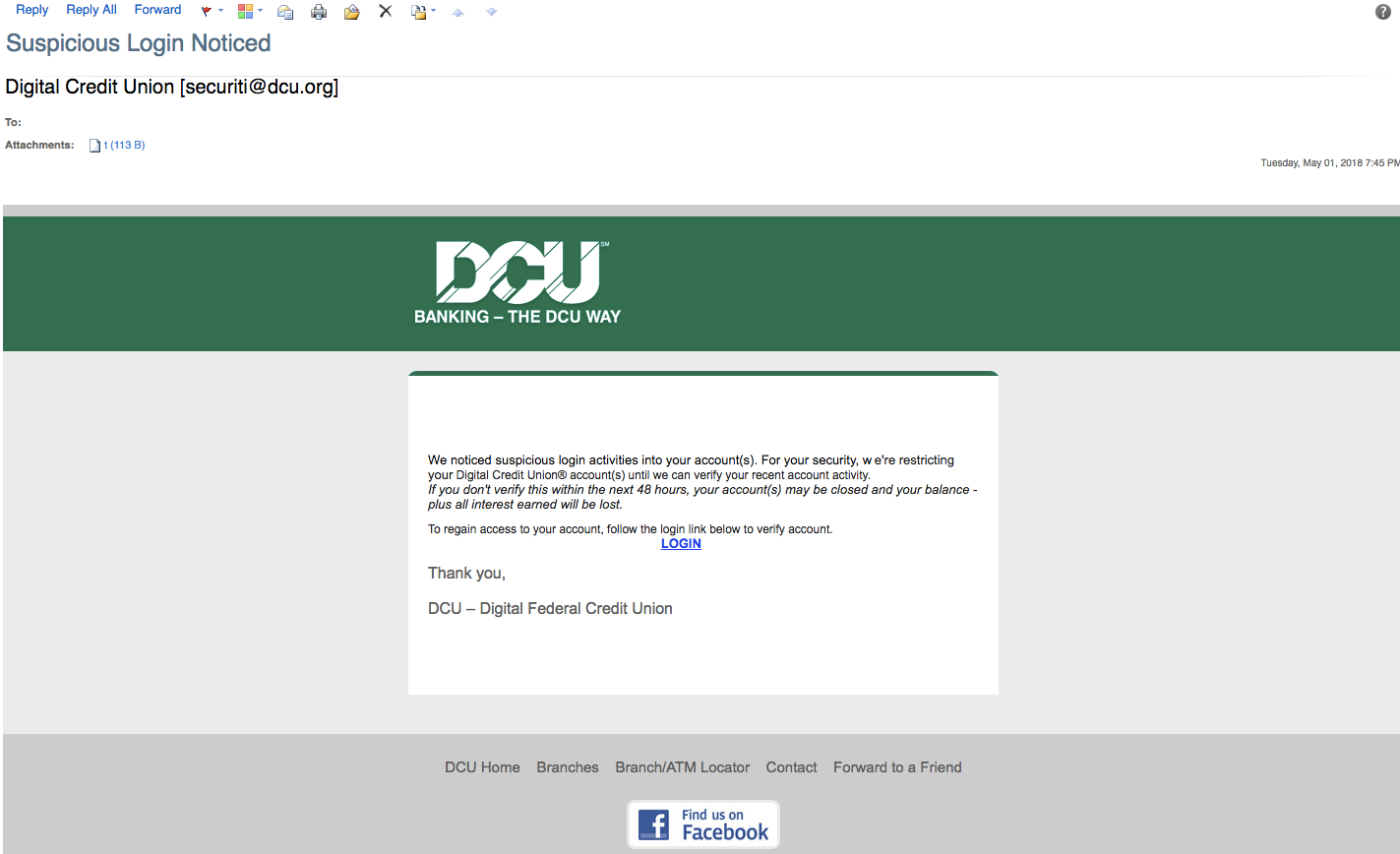

Computer-related forgery involves impersonation of legitimate individuals, authorities, agencies, and other entities online for fraudulent purposes. Cybercriminals can impersonate people from legitimate organizations and agencies in order to trick them into revealing personal information and providing the offenders with money, goods and/or services. The email sender pretends to be from a legitimate organization or agency in an attempt to get users to trust the content and follow the instructions of the email. Either the email is sent from a spoofed email address (designed to look like an authentic email from the organization or agency) or from a domain name similar to the legitimate organization or agency (with a few minor variations).

A common technique used is the sending of an email to targets with a website link for users to click on, which might either download malware onto the users' digital devices or sends users to a malicious website that is designed to steal users' credentials ( phishing). The "spoofed" website (or pharmed website) looks like the organization's and/or agency's website and prompts the user to input login credentials. The email provides different prompts to elicit fear, panic and/or a sense of urgency in order to get the user to respond to the email (and complete the tasks requested in the email) as soon as possible (see Image 1 below), such as the need to update personal information to receive funds or other benefits, warnings of fraudulent activity on the user's account, and other events requiring the target's immediate attention.

This tactic is not targeted, the email is sent en masse to catch as many victims as possible. A targeted version of phishing is known as spearphishing. This form of fraud occurs when perpetrators are familiar with the inner workings and positions of company employees and send targeted emails to employees to trick them into revealing information and/or sending money to the perpetrators. Another technique involves cybercriminals pretending to be higher level executives in a company (part of the C-suite - Chief Executive Officer, Chief Financial Officer and Chief Security Officer), lawyers, accountants, and others in positions of authority and trust, in order to trick employees into sending them funds. This tactic is known as whaling because it yields the highest payout.

The US toy company Mattel was a victim of whaling. The cybercriminals behind this attack had been surreptitiously monitoring the company's networks and communications for months prior to the incident. After an announcement was made that a new CEO was appointed, the cybercriminals used the identity of the new CEO (Christopher Sinclair) to perpetrate the attack. Particularly, the cybercriminals sent a message as Christopher Sinclair asking the recipient to approve a three-million-dollar transfer to a bank in Wenzhou, China, to pay a Chinese supplier. As the request came from the CEO, the employee transferred the money but later contacted the CEO about it. The CEO denied making the request. Mattel subsequently contacted US law enforcement, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, their bank, and Chinese law enforcement authorities (Ragan, 2016). The timing of the incident (the money had been transferred on the eve of a holiday) gave Chinese authorities time to freeze the accounts before the banks opened, enabling Mattel to recover its money.

Phishing via telecommunications is known as vishing (because a voicemail message is left that is designed to get the target to call a number and provide personal and/or financial data), and phishing via text messaging is known as smishing (or SMS phishing).

Article 8 of the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime defines computer-related fraud as "intentional… and without right, the causing of a loss of property to another person by…any input, alteration, deletion or suppression of computer data,…[and/or] any interference with the functioning of a computer system, with fraudulent or dishonest intent of procuring, without right, an economic benefit for oneself or for another person." This cybercrime is also prohibited under Article 11 of the Arab Convention on Combating Information Technology Offences.

Computer-related fraud includes many online swindles that involve false or misleading promises of love and companionship ( catphishing), property (through inheritance scams), and money and wealth (through lottery scams, investment fraud, inheritance scams, etc.). The ultimate goal of these scams is to trick the victim into revealing or otherwise providing personal information and/or funds to the perpetrator (a form of social engineering fraud). This tactic, as the name implies, uses social engineering (a term popularized by a US hacker, Kevin Mitnick), the practice "of manipulating, deceiving, influencing, or tricking individuals into divulging confidential information or performing acts that will benefit the social engineer in some way" (Maras, 2014, p. 141).

The most well-known computer-related fraud involves a request for an advance fee to complete a transfer, deposit or other transaction in exchange for a larger sum of money ( advanced fee fraud a.k.a., 419 scam). While the story of the perpetrators changes (they pose as government officials, bank officials, lawyers, etc.), the same tactic is used - a request for a small amount of money, in exchange for a large amount of money.

In addition to the online schemes, financial (or economic) fraud, such as bank fraud, email fraud, and debit and credit card fraud, is also perpetrated online. For example, debit and credit card data that has been illicitly obtained is sold, shared, and used online. A 2018 international cybercrime operation led to the closure of one of the most well-known online illicit carding forums, Infraud, which sold and shared stolen credit and debit card data and banking information (DOJ, 2018). The personal, medical, and financial information bought, sold, and traded online could be used to commit other crimes, such as identity-related crime, whereby the perpetrator unlawfully assumes and/or misappropriates the identity of the victim and/or uses the identity and/or information associated with the identity for illicit purposes (UNODC, n.d.). The type of data targeted by criminals includes identity-related information, such as identification numbers (e.g., social security numbers in the United States), identity documents (e.g., passports, national identifications, driver's licenses, and birth certificates), and online credentials (i.e., usernames and passwords) (UNODC, 2011, p. 12-15). Identity-related crime may or may not be financially motivated. For example, fraudulent identity documents (e.g., passports) could be purchased online for use in travel (UN-CCPCJ, 2017, p. 4). These types of crimes, as well as economic fraud, are facilitated online through the sending of unsolicited emails ( spam), newsletters, and messages with links to websites, which are designed to mislead users and trick them into opening the emails and newsletters or clicking on links in the emails, which may contain malware or be designed to send them to pharmed websites.

Article 10 of the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention criminalizes "offences related to infringements of copyright and related rights." Similarly, Article 17 of the Arab Convention on Combating Information Technology Offences prohibits "offences related to copyrights and adjacent rights."Copyrights "relate … to literary and artistic creations, such as books, music, paintings and sculptures, films and technology-based works (such as computer programs and electronic databases)" (WIPO, 2016, p. 4).

There are several international treaties relating to copyright protection, including the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works of 1886, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights of 1994, and the WIPO Copyright Treaty of 1996. Regional laws also exist with respect to intellectual property. A notable example of the infringement of copyright protection is digital piracy (e.g., the unauthorized copying, duplication, or distribution of a movie protected by copyright law).

Copyrighted works are considered a form of intellectual property, which is defined by WIPO as "creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce." Article 2(viii) of the Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) of 1967 holds that

intellectual property…include[s] rights relating to: … literary, artistic and scientific works, … performances of performing artists, phonograms and broadcasts, … inventions in all fields of human endeavour, … scientific discoveries, … industrial designs, … trademarks, service marks and commercial names and designations, … protection against unfair competition, and all other rights resulting from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary or artistic fields.

Intellectual property, therefore, includes not only copyrights (e.g., books, music, film, software, etc.), but also trademarks (i.e., names, symbols or logos belonging to a brand, service, or good), patents (i.e., novel and unique creations, innovations, and inventions) and trade secrets (i.e., valuable information about business processes and practices that are secret and protect the business' competitive advantage). Intellectual property is explored in greater detail in Cybercrime Module 11 on Cyber-Enabled Intellectual Property Crime.

According to the 2013 UNODC Draft Cybercrime Study, "computer-related acts causing personal harm" include "the use of a computer system to harass, bully, threaten, stalk or to cause fear or intimidation of an individual" (17). Examples of these types of cybercrimes are cyberstalking, cyberharassment, and cyberbullying. These cybercrimes are not included in multilateral and regional cybercrime treaties (e.g., the Cybercrime Convention; African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection; and Arab Convention on Combating Information Technology Offences).

Cyberstalking, cyberharassment, and cyberbullying have been used interchangeably. Some countries refer to any act that involves the child in either a victim or offender status as cyberbullying (e.g., Australia and New Zealand), while states within the United States use the term cyberbullying to refer to acts perpetrated by and against children. Some countries do not use the term cyberbullying, but instead use the term cyberharassment or cyberstalking, or different terms such as cybermobbing (in Austria and Germany) to describe cyberbullying (European Parliament, Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2016, 24-25), while others do not use any of these terms. With regards to the latter, Jamaica, for example, prohibits "malicious and/or offensive communications" under Article 9(1) of the Cybercrime Act of 2015, which criminalizes the use of "(a)…a computer to send to another person any data (whether in the form of a message or otherwise) that is obscene, constitutes a threat, or is menacing in nature; and (b) intends to cause, or is reckless as to whether the sending of the data causes, annoyance, inconvenience, distress, or anxiety, to that person or any other person."

In 2017, Latoya Nugent, a human rights activist, was charged with and arrested for violating Section 9 of Jamaica's Cybercrimes Act of 2015, for posting the names of perpetrators of sexual violence on social media. The charges against her were subsequently withdrawn. This section of the law, which proscribes online malicious communications, has been criticized for unjustifiably restricting freedom of expression (Barclay, 2017). A similarly worded section of a law in Kenya (Section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communication Act) was repealed because it was viewed by a national court as unconstitutional due to its vague and imprecise language and its lack of clarity on the types of expression (or speech) that would be considered illegal under the Act ( Geoffrey Andare v Attorney General & 2 others, 2016).

Read Cybercrime Module 3 on Legal Frameworks and Human Rights for a discussion on the relationship between cybercrime laws and human rights.

While there are no universally accepted definitions of these types of cybercrime, the following definitions that cover essential elements of these cybercrimes are used in this Module and in other Modules of the UNODC Teaching Module Series on Cybercrime (Maras, 2016):

What differentiates these cybercrimes is the age of the perpetrators (i.e., only children engage in and are victims of cyberbullying), and intensity and prevalence of the cybercrime (cyberstalking involves a series of incidents over time, whereas cyberharassment can involve one or more incidents). These cybercrimes and their differences are explored in further detail in Cybercrime Module 12 on Interpersonal Cybercrime.

Information and communications technologies have been used to facilitate child grooming. Child grooming is the process of fostering rapport and trust through the development of an emotional relationship with the victim (Maras, 2016, p. 244). According to Whittle at al. (2013), "grooming varies considerably in style, duration and intensity; often reflecting the offender's personality and behavior" (63). The offender may manipulate the victim using a variety of power and control tactics, including (but not limited to): adulation, gifts, isolation, intimidation, threats, and/or force (Berlinger and Conte, 1990; O'Connell, 2003; Mitchell, Finkelhor, and Wolak, 2005; Ospina et al., 2010; Maras, 2016) as well as feigning shared interests, or building trust by mimicking a child's apparent sense of isolation. Child grooming can occur on social media platforms, over email, in chat rooms, through instant messaging services, and via apps, among other areas. A 2017 BBC investigation revealed that the Periscope app, which enables live broadcasting anywhere in the world, was being used by predators to groom children. The predators who contacted the children who were broadcasting live made sexualized comments about the children and some even requested children to remove their clothes (BBC, 2017).