Illicit firearms can come from many sources and determine in part the size of the illicit traffic. The sections below summarize the key sources of illicit supply.

Most types of illicit sources form three major categories:

The United Nations Firearms Protocol considers firearms illicit when manufactured without a licence or authorization from a competent authority of the State, or in the case of manufacture or assembly without a marking compliant with the Protocol requirements. Firearms manufactured from illicitly trafficked parts and components are also illicit and subject to criminal sanction.

Most firearms today begin their life cycle as legal products but illicit manufacture occurs in several ways.

Prior to the advent of large-scale factory production, small-scale craft workshops produced all firearms. That artisan form of manufacture persists today in some parts of the world. Blacksmiths in West Africa, for example, produce a range of small arms including pistols and shotguns (Vines, 2005: 352-53). Artisan firearm manufacture is well- developed in Ghana, and Pakistan produces a wide range of inexpensive, artisan-crafted small arms, including revolvers and shotguns (Small arms Survey, 2011). Most of these productions are not fully recognized, nor authorized, by national authorities, and although they violate national law as well as regional and international instruments to which the country has committed, are tolerated until a more comprehensive regulatory framework is applied, as the case of Ghana exemplifies.

Amateurs working at home or in sophisticated workshops may copy and fabricate original firearm designs. According to the Firearm Blog (2014: 1), " Illicitly 'homemade' submachine guns feature very prominently in firearms seizures by police across South America, Brazil in particular. These weapons vary in their level of sophistication though a large number appear to be semi-professionally produced. In a recent study of over 14,488 firearms seized between 2011 and 2012 in Sao Paulo alone, 48% of submachine guns analyzed were reportedly homemade."

Clandestine factories are not a prerogative of particular countries and regions only. By way of example, Salcedo-Albarán and Santos (2017) report two cases of illegal homemade gun factories detected and dismantled in Australia and in the Philippines. According to local media reports, the Australian home factory was producing mainly .22 rifle replicas, whereas the one detected in Pampanga, Philippines suspected of illegal fabrication of homemade caliber .22 pen guns.

Firearms are illicit when made without production licences, or produced surplus to licence agreements and without appropriate authorization from competent state authorities. The same applies to firearms produced without identification or, in rare cases, with the same identification markings that facilitate tracing.

Unlike artisan production and the copying of design weapons, a third form of illicit manufacturing is through rudimentary forms of production. Criminals often produce these firearms when they cannot access others; instead, they use components not originally designed as part of a firearm, but have been adapted for this purpose.

With the advent of 3D printing, illegal software produced individual 3D printed firearms that looked rather unlike weapons on the legal market (Daly and Mann, 2018). Their purpose was to fire a bullet or two at close range, either for self-defence, or criminal activity where a great deal of firepower was not required. More recently, police raided a ' gun factory' comprising 3D printers in Queensland, Australia. Four " Uzi-style" submachine guns, three silencers and two handguns were seized (Crockford, 2016).

Finally is the instance of factory-produced illicit copies of existing designs. During the Balkans War, machine shops in Croatia manufactured an Uzi machine pistol variant to meet domestic demand. In 2003, a consignment of 30 such weapons found concealed in a cargo lorry was intercepted at the port of Dover (Bazargan, 2003).

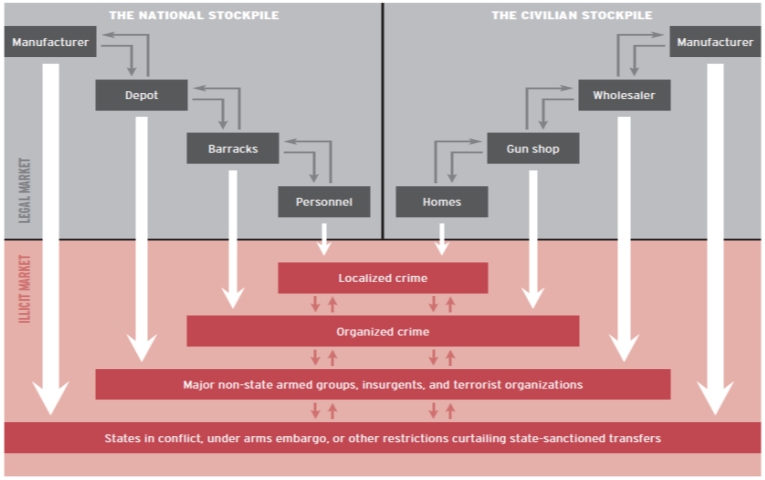

' Diversion' is the term used for the movement - physical, administrative or otherwise - of a firearm from the legal to the illicit realm (MOSAIC, 2014). Diversion can occur at all points of the life cycle of a firearm, posing various challenges for arms control.

One documented phenomenon is ' stockpile diversion', either from civilian or national (i.e. government) stockpiles. Another is the diversion of firearms during shipment from one location to another, for example, when forged documentation facilitates the arms transfer to a destination not authorized by the exporting government. It is also widely recognized that the pilfering of weapons stored in a depot can lead to diversion. Illicit brokers or dealers who arrange the necessary elements of an illicit shipment facilitate illicit cross border firearms trafficking and diversion. Legally owned firearms may lose that status if the owner loses their licence or fails to keep them registered.

Figure 4.2 illustrates the diverse types of stockpiles and their affiliated types of diversion:

Illicit arms can be manufactured in legitimate factories but fraudulently diverted or stolen from factory stores, State held storage facilities, military facilities or private households. In the most basic instance, an employee might, for example, steal a pistol after not marking it and sell it on the black market. Theft of weapon components and ammunition is also an issue.

The end of the Cold War saw significant downsizing of the military forces of NATO and the former Warsaw Pact, releasing large quantities of surplus arms and ammunition on to the international market at bargain prices. A great deal of this weaponry ended up in areas of conflict (Greene, 1999; Carr, 2008). Many former Soviet weapons found buyers in the world's new conflict zones as States and criminal entrepreneurs discovered that former military weapon stocks were among their most saleable commodities. As Chivers (2010) has suggested with no little irony, it took the global triumph of neo-liberalism to make a global commodity of communism's best gun. As Holtom (2007) comments, ' in the post-Soviet era, commercial considerations replaced ideological factors, with considerable decentralisation and lack of State control characterising SALW export policies during the early 1990s'.

Theft and fraud from points of production, stockpiles or military installations, or police sources, can contribute to illegal firearm supplies. Stockpile insecurity is a major global problem. Many countries lack the capacity to safeguard weapons owned by the State-military and domestic security forces. In times of military or political turmoil, State held stockpiles are particularly at risk of attack and looting by rebel groups (e.g. Libya) (CAR, 2016). Globally, there is a major effort to secure these stockpiles and reduce the illicit firearm acquisition achieved via this method.

Concern about soldiers returning home with battlefield souvenirs surfaced in the United Kingdom following the first and second Gulf Wars (Owen, 2013), although this was by no means the first or only emergence of this issue. Victors and survivors in the wake of military encounters also frequently acquire weapons. Berman et al. (2017) likewise found several instances of UN peacekeepers allegedly selling, or having forcibly removed, their weapons by rebel forces following ambushes or confrontations. The research was reported in the following terms: ' UN-backed peacekeepers have lost enough guns and ammunition in sub-Saharan Africa over the past two decades to arm an army, according to a study by the Small Arms Survey' (Berman et al., 2017; Reinl, 2017).

Civilian ownership represents the largest type of firearms holdings globally. There are many opportunities for terrorists and criminals to acquire weapons illicitly from civilians (including criminals, gang members, and private security companies). Outright theft from homes or vehicles, or through robberies, is one route. Owners lose their firearms and civilians illicitly sell their weapons in black market transactions. State regulations regarding civilian possession vary significantly and create opportunities to acquire firearms in a State with lax laws on possession, and illicitly traffic them to States with stricter laws, as shown earlier seen in respect of the United States, Mexico and Canada.

Firearms held by private security companies, where those companies exist and operate legally also fall under the category of civilian held arms. Thefts and losses of firearms from private security companies can be in larger amounts than from private households. These cases are also of great concern when there are inadequate national regulatory frameworks in place that properly control firearms and activities associated with them.

Firearms dealers have opportunities to fabricate licensing documentation (' cloning') and could use some discretion regarding the undertaking of checks on firearm purchasing eligibility. Their combined knowledge of firearms and their networks of contacts will also provide opportunities to acquire and sell unregistered weapons, ammunition and components.

Module 3 on The Legal Firearms Market describes how firearms exports must be accompanied by a document declaring what is in the shipment and where it is going. The world is rife with cases where transfers of arms are mislabeled as other commodities, like " machine parts", and go to a country other than the one documented. Diffusion into the recipient State then occurs among those who misuse them in crime, terrorism or armed violence against other groups, or the State itself. Ideally, all legal shipments should correspond with an End User Certificate (EUC) signed by the exporting and importing States that specifies who will use the arms and that the firearms should not be re-exported without the permission of the exporting State. This does not happen always; many transfers become illicit on arms re-export to those who misuse them without the permission of the exporting State (Bromley and Griffiths, 2010). Various ways in which EUCs are altered, amended or fabricated facilitate weapon re-export or ' diversion', leading to firearm illegality.

National firearms regulations typically restrict the types of firearms that civilians might legally own, but do not necessarily eliminate demand. Accordingly, prohibitions on handguns in particular have led some parties to devise new means of acquiring these or comparable firearms. One common method involves mechanically altering an accessible replica firearm to function in a similar way as a restricted firearm. This process is generally known as a firearms conversion and has been observed worldwide' (Small Arms Survey, 2015). According to the Small Arms Survey's (2015: 1) research, " blank-firing handguns are the most commonly converted replicas worldwide, but many other types of replica firearms are also highly convertible."

Conversion may be possible for many types of replica firearms, although certain models are more appealing because of their design, materials used in their construction, and the ease with which they might be converted. Ease of access to conventional firearms, legal restrictions, the cost of pistols, and the fact that replicas may be untraceable which especially appeals to criminals, all impact on demand for converted firearms (Squires, 2014). The conversion of non-lethal starter pistols into lethal weapons is very popular with criminals in Europe (see the online video under Additional Teaching Tools).

Globally, law-enforcement agencies frequently confiscate large numbers of replica firearms and often express concern about their possible conversion. Firearms conversion is a global practice, and in some places taking on the dimensions of a small-scale manufacturing process. While European nations most frequently report the problem, converted weapons appear in many countries, including most recently in several African countries. The South Eastern and Eastern Europe Clearinghouse for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons (SEESAC), a UNDP SALW project in the Balkans, also reported on this problem in their paper Convertible Weapons in the Western Balkans (SEESAC, 2009). The conversion of weapons into fully functioning firearms is, strictly speaking, a form of illicit manufacturing, and subject to criminal sanction under the terms of the United Nations Firearms Protocol. This Protocol considers illicit all firearms manufactured without a valid authorization or licence issued by a competent authority, and/or without the required marking (Article 3(d) and Article 5 Firearms Protocol).

Similar considerations apply in respect of weapon reactivation. There is a global market for ' iconic' souvenir firearms, either fake replicas of original arms or deactivated weapons such as those, for example, employed in theatrical and cinematic productions. The law requires the deactivation of certain types of arms such as these.

To be considered deactivated, the United Nations Firearms Protocol requires that " all essential parts of a deactivated firearm are to be rendered permanently inoperable and incapable of removal, replacement or modification in a manner that would permit the firearm to be reactivated in any way" (Article 9 Firearms Protocol). However, in practice countries have different deactivation criteria in place, which can allow a firearms expert to reverse the process of deactivation. Depending upon the extent of the ' deactivation' process to which such firearms have been subjected (different nations have more or less rigorous deactivation standards, but some individual countries may have older and newer deactivation specifications that differ) it may be possible for skilled persons to bring these weapons back into full working order.

The problem of illicitly reactivated weapons has become of particular concern in Europe. In recent years, high-profile terrorist attacks have been committed using reactivated weapons. One reason for this particular form of illicit trafficking in Europe seems to be the fact that in many European countries the legal access to other firearms is more difficult. Criminals have resorted to this modality because it has allowed them to operate below the radar, thanks to larger disparities between national deactivation criteria among European Union Member States. By way of example, forensic scientists examined a significant cache of reactivated weapons seized by Belgian police in the late 1990s (Migeot and De Kinder, 1999), while several workshops for bulk firearm reactivation have been unearthed in the United Kingdom. Police also uncovered a supply chain of reactivated Mac-10 sub-machine guns arming the criminal underworlds of Dublin, Manchester, Glasgow and London (Walsh, 1999). Traced to a rented workshop in Hove, East Sussex, a police raid found 40 deactivated Mac-10s and the tools and components to restore them to full working order, subsequently linking them to numerous shootings and crime scenes around the country. In their deactivated form, the weapons would cost around £100 each but could command a price ten times that when reactivated.

In 2016, evidence emerged that police in Kent seized a consignment of 22 AK model reactivated assault rifles and nine ' Skorpion' machine pistols, the largest haul of illegal firearms intercepted in the United Kingdom. The same Slovakian firearms dealer supplied the weapons as used by terrorists in the ' Charlie Hebdo' Paris shootings of January 2015. The Slovakian firm sold so-called deactivated ' acoustic expansion weapons' as souvenirs, although the deactivation process could be easily reversed by the removal of pins inserted into the weapon barrels (Laville, 2016).

Antique firearms might be re-engineered to fire contemporary ammunition, and bespoke ammunition manufactured to fit obsolete caliber weapons. Cutting down stolen long guns, rifles and shotguns make them more easily portable and concealable by offenders.

The collection and destruction of surplus firearms and SALW has been part of the global effort to lower the harmful effects of illicit and indiscriminate firearm supply since the mid-1990s. These weapons become illicit in several ways. Some of them take a long time to destroy and can be put in the same stockpiles that criminals and terrorists may steal from. Some countries may have very loose restrictions on the acquisition of surplus SALW and firearms, while others may re-sell surplus or accumulated weapons for the purposes of raising revenue. Despite States paying more attention to the disposition of surplus weapons, many from previous conflicts remain in circulation for long periods, for example through servicing, repair and recycling by illegal armorers, or spare parts purchased on the Internet.