Criminal offences are the legal ground to accuse and convict a person found guilty of having committed a specific illicit conduct (action or omission), prohibited by law, which must be proven in court and established by a judicial authority. This is the basic and fundamental principle of legality, according to which nobody can be convicted of a crime that does not exist (nullum crimen sine lege).

Criminal offences are generally made up of parts, referred to as ‘constitutive elements’, which define and characterize the offence and which have to be proven in court. With exceptions, every crime has at least three elements:

The criminal act can be defined as unlawful bodily movement or conduct, and can consist of:

The criminal intent, or mens rea, is an essential element of most crimes. Jurisdictions vary in their approach to defining criminal intent, but generally it is a subjective test. Intent should not be confused with motive, which is the reason the defendant commits the criminal act or actus reus. Motive can generate intent, support a defence, and be used to determine sentencing. However, motive alone does not constitute mens rea and does not act as a substitute for criminal intent.

Attempt: Subject to national laws, a person who does not manage to complete the offence may still be found guilty of attempting to commit the offence. In many jurisdictions, offences related to firearms are punished with the same penalty if attempted or completed.

Proving the offence: Generally, the prosecution has the burden of establishing all elements of an offence in order to prove a person has committed the offence. In most firearms offences, part of the exercise will include proving the existence of a firearm, and eventually its functionality.

When dealing with firearms criminality in relation to an offence, there are essentially three primary issues to consider:

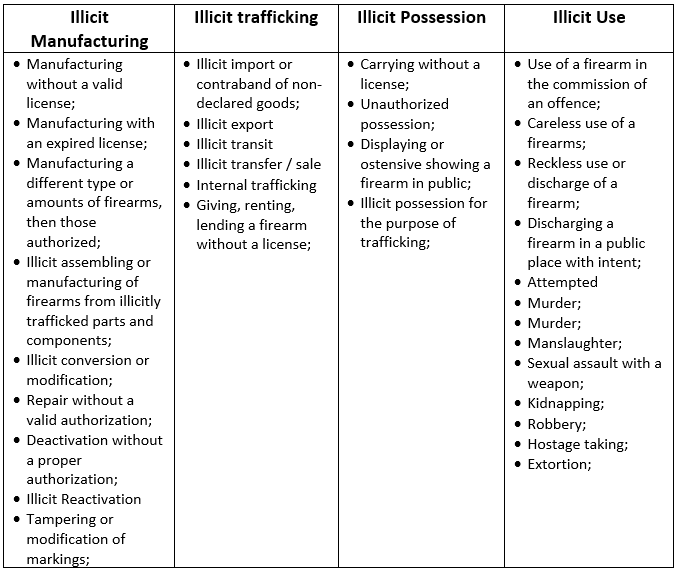

In many national jurisdictions, firearms offences are divided into four main categories of offences:

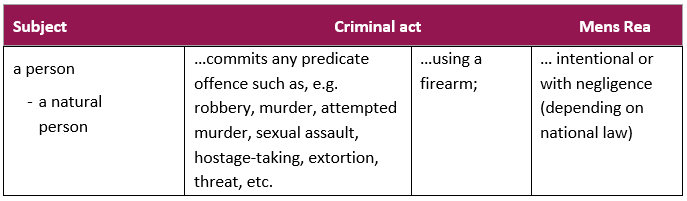

Use offences typically include all cases in which firearms are used by, or readily available for use by an offender to facilitate the commission of an offence. Use offences include offences such as murder, attempted murder, robbery, sexual assault with a firearm, hostage-taking, extortion inter alia.

Depending on the legal system, not all States will have laws specifically differentiating between the substantive offence and the use of a firearm to commit it. For example, a charge of robbery, regardless of the methods used to commit it, may still be termed a robbery, and the State will consider the use of a firearm as a general aggravating circumstance of the principal offence. However, many countries, recognizing the seriouness of firearms and the increased danger to public safety that they pose, will create a specific offence related to the firearm use (ie. robbery with a firearm). Although this generally puts an increased burden of proof on investigators and prosecutors, resulting convictions usually carry increased penalties, the primary purpose of which is to act as a detterent to those who are involved in the illegal possession and use of firearms (UNODC, 2019).

Proving the offence

It is not necessary that the firearm has actually been discharged; pointing the firearm at somebody and threatening with its use would qualify for its use.

In addition to the commission of the predicate offence, elements that need to be proven include that the item used was actually a firearm (regardless of its appearance), as defined by national law. In some cases, there is no need to prove the functionality of the firearm, as the mere threat of using it is enough to qualify the aggravated or specific offence; for example, in cases where firearms serve an intimidating function. However, in cases where the firearm was used to cause harm or death, the proof of the functionality of the firearm is an essential element that needs to be established by an expert in court. In these cases, as well as proving that the item is a firearm as defined by domestic law, it also needs to be proven that the specific item is capable and functioning like a firearm, meaning that it is capable of expelling a bullet or a shot, and that it is the item that has actually caused the injury or death.

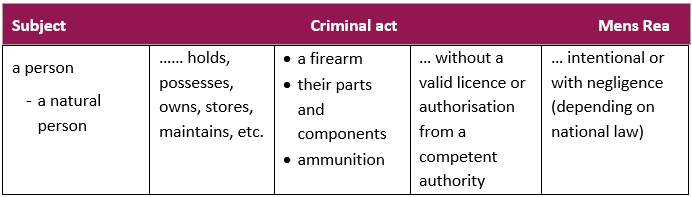

Illicit possession applies to all cases where the offender has in their personal possession or custody a firearm without a proper authorization. This category is often very large and encompasses very different situations. These range from mere possession to the illicit carrying, and up to possession linked to illicit transfer and trafficking amongst others, depending on national laws. Contrary to use offences, possession offences are typical offences where the firearm itself constitutes the principal element of the substantive offence.

Unlike offences linked to the illicit manufacturing and trafficking in firearms, due to a large variety in national firearms control regimes, there is no universal understanding on legal ownership and consequently of the offence of illicit possession. Although most countries use the same or a similar terminology, there are very different concepts and understandings of what constitutes an illicit possession in different countries, both in terms of concrete conditions and requirements for obtaining an authorization, and in the type and number of firearms that are subject to such authorization. This divergence is particular evident when it comes to civilian ownership. Module 6 on National Regulations on Firearms provides specific examples on this issue from various national legal frameworks.

Proving the offence

Elements that need to be proven include, on the one hand, that the object in question is a firearm, their parts and components, and ammunition, and that the person lacks the required authorization in accordance with national law. A firearm that was permanently rendered inoperable through what is called ‘permanent deactivation’ is in many countries no longer considered a firearm, and thus subject to specific authorization. Also, as far as parts and components and ammunition are concerned, it is important to relate to the domestic regulation and establish whether the type of ammunition falls within the scope of what the law subjects to national control, as this too can depend on technical specifications that are provided by law or implementing decrees.

The offences of illicit manufacturing and illicit trafficking also encompass a wide range of conducts and are specifically defined in the UN Firearms Protocol. Given the Firearm Protocol’s global and legally binding nature, this Module refers to the offences as established under it, notwithstanding the fact that their domestic norms may divert in part from the international definition and the elements of the offence as provided in the legal instrument.

Other associated offences contained in the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) will be addressed as well, to the extent to which they contribute to support the criminal justice response to counter firearms criminality.

The Firearms Protocol establishes in its article 5 the obligation for States parties to establish as a criminal offence a number of conducts related to the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition.

1. Each State Party shall adopt such legislative and other measures as may be necessary to establish as criminal offences the following conduct, when committed intentionally:

(a) Illicit manufacturing of firearms, their parts and components and ammunition;

(b) Illicit trafficking in firearms, their parts and components and ammunition;

(c) Falsifying or illicitly obliterating, removing or altering the marking(s) on firearms required by article 8 of this Protocol.

2. Each State Party shall also adopt such legislative and other measures as may be necessary to establish as criminal offences the following conduct:

(a) Subject to the basic concepts of its legal system, attempting to commit or participating as an accomplice in an offence established in accordance with paragraph 1 of this article; and

(b) Organizing, directing, aiding, abetting, facilitating or counselling the commission of an offence established in accordance with paragraph 1 of this article.

These can be divided in three groups of central offences:

The aim of these offences is to ensure that that States parties establish a legal framework within which legitimate manufacturing and transfer of firearms can be conducted, and which will allow illicit transactions to be identified to facilitate the prosecution and punishment of offenders.

It should be noted that the purpose of the Firearms Protocol is to prevent the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition. As such, the scope of application of the investigation and prosecution of offences established in accordance with article 5 of the Firearms Protocol is where those offences are both (a) transnational in nature, and (b) involve an organized criminal group, as defined in UNTOC. However, these two elements must not be made elements of the offences under domestic law (Article 3 (2) UNTOC) (UNODC, 2004: 6).

An offence is of transnational in nature when the offence:

(a) is committed in more than one State;

(b) is committed in one State but a substantial part of its preparation, planning, direction or control takes place in another State;

(c) is committed in one State but involves an organized criminal group that engages in criminal activities in more than one State; or

(d) is committed in one State but has substantial effects in another State.

“Organized criminal group” shall mean:

“A structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with this Convention, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit”.

Both the UN Firearms Protocol and UNTOC establish a legal obligation for States parties to establish certain conducts as criminal offences when committed intentionally.

Article 34, paragraph 3, of UNTOC expressly allows States to adopt “more strict or severe” measures than those provided for by the Convention (UNODC, 2004: 36). Given the varying degrees and definitions of mens rea in national jurisdictions, some jurisdictions may have chosen to include and specify the level of intent required for each article in accordance with their legal system and national practice. It is also important to note that the element of intention refers only to the conduct or action that constitutes each criminal offence and should not be taken as a requirement to excuse cases in particular where persons may have been ignorant or unaware of the law that constituted the offence. (See also the Legislative Guide, para. 174 (d)).

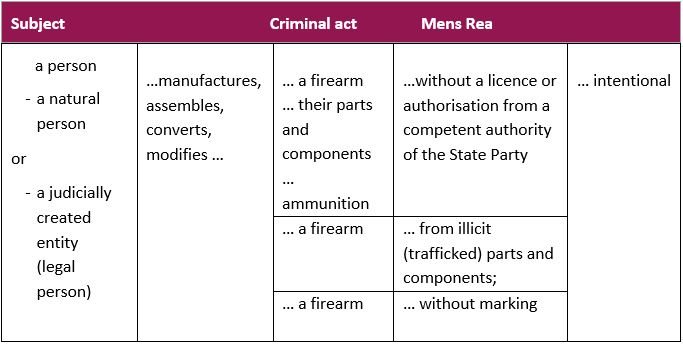

Article 3, paragraph (d) of the Firearms Protocol provides the following definition of “illicit manufacturing”:

“Illicit manufacturing” shall mean the manufacturing or assembly of firearms, their parts and components or ammunition:

(i) From parts and components illicitly trafficked;

(ii) Without a licence or authorization from a competent authority of the State Party where the manufacture or assembly takes place; or

(iii) Without marking the firearms at the time of manufacture, in accordance with article 8 of this Protocol;"

The criminalization of illicit manufacturing encompasses the following three different conducts:

The criminalization of these activities is intended to ensure that all stages of the manufacturing process from raw materials to finished firearms are included. More specifically, the intent of the first offence - manufacture or assembly from illicit parts and components - is to ensure that the basic import, export and tracing requirements of the Protocol will not be circumvented by manufacturing all parts and components of a firearm and carrying out exports before assembly into the finished product.

The second offence ensures that the manufacturing of the firearms will not take place covertly since a competent authority must authorize the activity.

The intent of the third offence is to ensure that the manufacturing process includes markings sufficient for tracing.

Proving the offence

Elements to be proven include the manufacturing process, the end product, which is a firearm, its parts and components, or ammunition, the absence of a licence or authorization by a competent authority, or the lack of proper marking as established by national law.

The UN Firearms Protocol defines “illicit manufacturing”, but not the term “manufacturing”. The report of the Group of Governmental Experts established pursuant to General Assembly resolution 54/54 V (A/CONF.192/2) provides in Annex I that manufacturing consists of the development, production, and licensed production of firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition, as well as the conversion or transformation of something into a firearm. Thus, the modification of a firearm and its characteristics, and the conversion of gas pistols and blank pistols into firearms, will fall under this definition. The re-activation of deactivated firearms can be also considered a form of manufacturing.

To prove that the end product was a firearm, its parts and components, or ammunition, it must meet the definition as outlined in article 3(a-c) of the Protocol.

“Firearm” shall mean any portable barrelled weapon that expels, is designed to expel or may be readily converted to expel a shot, bullet or projectile by the action of an explosive, excluding antique firearms or their replicas. Antique firearms and their replicas shall be defined in accordance with domestic law. In no case, however, shall antique firearms include firearms manufactured after 1899;

“Parts and components” shall mean any element or replacement element specifically designed for a firearm and essential to its operation, including a barrel, frame or receiver, slide or cylinder, bolt or breech block, and any device designed or adapted to diminish the sound caused by firing a firearm.

Ammunition” shall mean the complete round or its components, including cartridge cases, primers, propellant powder, bullets or projectiles, that are used in a firearm, provided that those components are themselves subject to authorization in the respective State Party.

It is important to note that the definition for these three items as identified in the Protocol may be much broader/inclusive according to those same national interpretations. For example, in some countries the completed frame or receiver of a firearm constitutes a firearm in and of itself (USA, Canada). However, in other countries, the firearm or an essential part of it, such as a receiver, that is only manufactured to a certain extent, for example up to 80% of completion, is not considered a firearm.

In practice, a firearms expert (such as a firearms forensic technologist, law enforcement expert or a civilian involved in the business of firearms production) versed in the manufacturing process of firearms will determine the status of the manufacturing process and whether its final product is that of the indicated item. This determination will have to be based on national interpretation.

The Protocol implicitly requires that manufacturers hold a licence or other authorization to manufacture firearms and ammunition. It also requires States to establish a competent authority responsible for issuing a licence or authorization to manufacture firearms. The reference to issuance by a “competent authority” of the State party involved refers to any official who is empowered to consider and issue licences or authorizations under the laws of that State party. The onus of proving the existence of a valid authorization or licence would fall upon the defence.

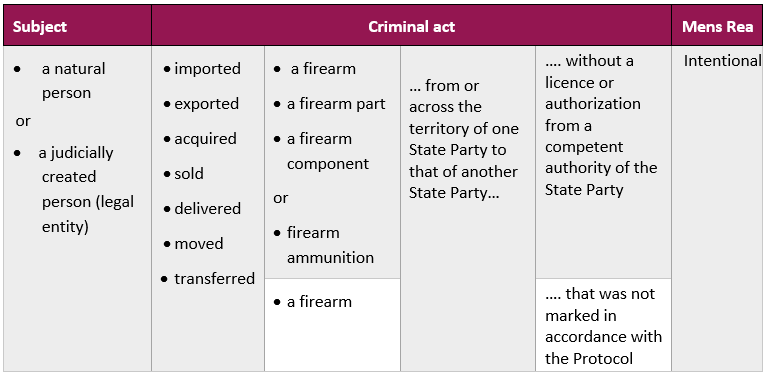

Article 5 of the Firearms Protocol refers to the obligation to criminalize illicit trafficking as one of the “central” offences established by the Protocol.

Article 3, subparagraph (e), defines illicit trafficking as:

… the import, export, acquisition, sale, delivery, movement or transfer of firearms, their parts and components and ammunition from or across the territory of one State Party to that of another State Party if any one of the States Parties concerned does not authorize it in accordance with the terms of this Protocol or if the firearms are not marked in accordance with [this] Protocol…

What constitutes “import” and “export” should generally be consistent with existing national law and international standards.

Article 3, subparagraph (e), of the Protocol establishes two specific mandatory criminal conducts in relation to illicit trafficking:

Article 8 requires marking in three instances:

Article 8 only mandates the marking of firearms. Those States which legislate beyond the mandatory requirements of the Protocol and require some form of marking for parts, components or ammunition should envisage a corresponding expansion of this provision of the Protocol.

The offences relating to illicit trafficking are intended to increase transparency associated with the cross-border movement of firearms and related items.

The first offence is intended to ensure that firearms and related items are sent to and through States only if the latter have agreed to receive the shipments. The system adopted in the Protocol creates this reciprocal approval process and has the effect of implicating more than just States parties to the Protocol. The reason for this is that a State party that is the exporting State will require authorizations from the importing and transit States even if the latter are not States parties to the Protocol.

The intent of the second offence is to ensure that the movement of firearms is only authorized if the firearms have markings sufficient for tracing.

Proving the offence

Unlike use and possession offences, illicit trafficking and manufacturing offences can be committed by a natural or a legal person.

The following criminal acts contained of the offence that must be proven are:

(a) The illicit transfer, which includes any of the following activities:

The definition of illicit trafficking provided under the Firearms Protocol refers intrinsically to a transnational offence. This includes nominal transfer of the ownership title, but it does not explicitly include internal transfers or transhipment. It is important to note that national definitions may differ from the Protocol offence. Some countries distinguish between internal and international trafficking, and qualify the latter as international trafficking or as illegal import, as opposed to the simple trafficking.

(b) The items, which include any of the following:

(c) A transnational element:

(d) The lack of either:

It is important to note that this last type of trafficking applies only to firearms that do not have the proper marking in accordance with the Protocol, not to parts and components or ammunition. However, as explained above, article 34, paragraph 3, of UNTOC expressly allows States to adopt “more strict or severe” measures than those provided for by the Convention or mutatis mutandis, the Protocol. In fact, some national laws also require the marking of parts and components, or of ammunition. The scope and extent of the illicit trafficking offence will depend on the national interpretation of the Protocol provision and its transposition into domestic law.

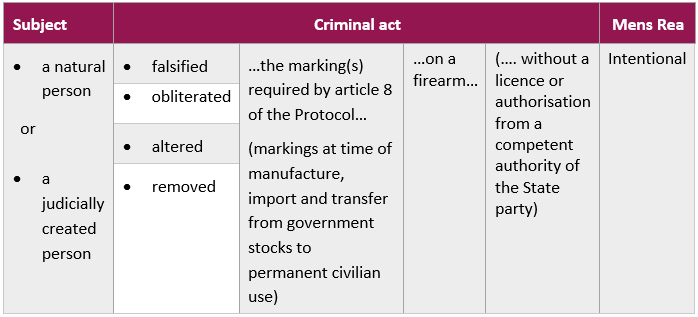

The third group of offences established under article 5 of the Firearms Protocol is related to the tampering with markings.

Article 5, subparagraph 1(c) states:

Each State Party shall adopt such legislative and other measures as may be necessary to establish as criminal offences the following conduct, when committed intentionally:…

(c) falsifying or illicitly obliterating, removing or altering the marking(s) on firearms required by Article 8 of [the] Protocol.

The provision defines two separate mandatory criminal offences:

(a) Falsifying firearm markings at the time of manufacture, import or transfer from government stocks to permanent civilian use; and

(b) Obliterating, removing or altering firearm markings.

Offenders seeking to frustrate efforts to identify and trace firearms used or intended for use in criminal offences, including trafficking, frequently attempt to remove or alter unique markings or render them impossible to read. For this reason, many States with previously established legislation requiring firearms to be marked have also established offences relating to tampering with such markings and article 5, paragraph 1 (c), of the Protocol contains the requirement for all States parties to implement such an offence.

The objective of the provisions is to criminalize those activities that render the markings on a firearm unintelligible or inaccurate, making it impossible to uniquely identify the firearm or trace it against past records created using the original marking. These generally support the policy of ensuring that firearms can be identified and traced. Such offences apply to all conduct that involves tampering with the markings at any time after the manufacturing or assembly process is complete, except for cases where markings are altered or added pursuant to some legal authority (Legislative Guide).

The inclusion of the word “falsifying” in paragraph 1 (c) is intended to create an offence that supplements the offence of illicit manufacturing. It includes any case where a firearm is marked at manufacture with markings that meet the requirements, but that are false in relation to any records that would subsequently be used to trace the firearm. Thus, for example, knowingly marking a firearm with the same number as another firearm would fall within the manufacturing offence, whereas affixing a marking that was unique, but gave a false country or place of manufacture, or was inconsistent with records kept by the manufacturer, or information transmitted to State records for later use in tracing would fall within the tampering offence.

The terms “obliterating, removing or altering” markings are intended to cover the full range of methods devised by offenders to prevent the successful reading of markings. Generally, prosecution of such offences will be supported by evidence from a law enforcement or forensic expert to the effect that this has taken place.

The provisions require States parties to criminalize the falsification of marking(s) on firearms required by article 8 of the Protocol, namely markings at the time of manufacture, import and transfer from government stocks to permanent civilian use. The term “civilian use” is to be understood as a broad category that covers all groups and actors that are not State controlled or owned, including private security companies and sports clubs.

The Protocol does not require States to establish as criminal offences failure to mark firearms under circumstances other than mentioned above. However, States are required to ensure firearms are marked at the time of disposal other than by destruction (under Protocol Article 6, paragraph 2) and, in some instances, upon deactivation (under Protocol Article 9). To ensure adherence to and the enforceability of these requirements, States may consider going beyond the Protocol requirement (pursuant to Article 34, paragraph 3, of UNTOC), and establishing additional offences and penalties associated with a failure to mark weapons properly or at all at the time of disposal other than by destruction or deactivation. Similarly, where States also require proof marks and the marking of weapons acquired by state agencies, States may decide to also extend the scope of the offence to these obligations (see UNODC Model Law on Firearms).

Proving the offence

The elements of the offence include:

The Protocol only requires States to establish the falsification of markings as a criminal offence when such falsification is intentional (i.e. when there is an intention on the part of the person marking the firearm to provide deceptive or misleading information as to the origins or life cycle of the weapon). In practice, States may decide to adopt a wider range of sanctions, including lower penalties, such as administrative sanctions, depending on the gravity of the offence and the level of intent.

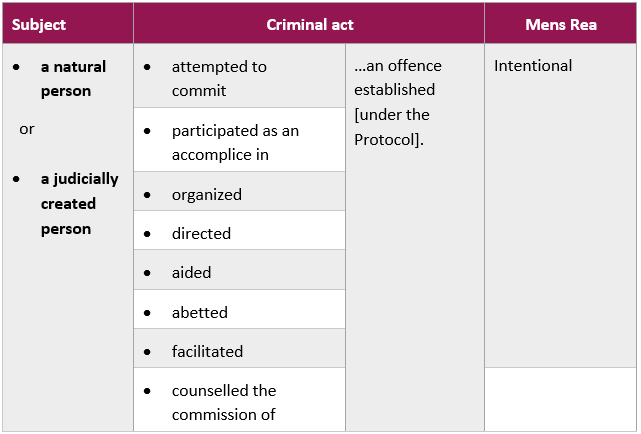

Article 5, paragraph 2, requires States to adopt legislative and other measures to establish as criminal offences the following:

These provisions are not specific to illicit manufacturing or trafficking and only need to be included if not already covered by general provisions in the national criminal code or law that are applicable to all crimes.

Proving the offence

In some countries, legal references to attempting to commit the offences are understood to include both acts perpetrated in preparation for a criminal offence and those carried out in an unsuccessful attempt to commit the offence, where those acts are also culpable or punishable under domestic law (A/55/383/Add.3, para. 6).

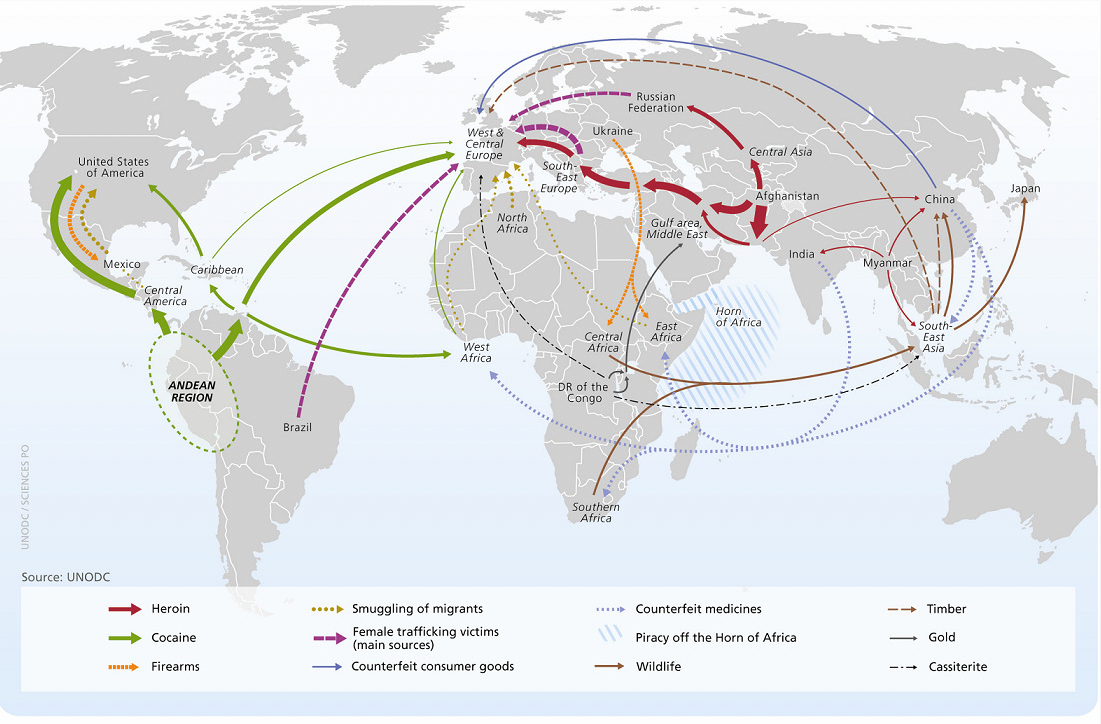

UNTOC provides the main and principal international framework to support the criminal justice response to transnational organized crime and related offences, including, of course, the specific firearms offences that are being addressed in this Module. Rather than providing a list (unavoidably incomplete) of offences typically linked to transnational organized crime, and cognisant of the dynamic and evolving nature of organized crime, the Convention adopts a broad scope of application and an inclusive approach to organized crime:

The Convention applies to the “prevention, investigation and prosecution” of:

The four core offences established by the Convention that States parties are obliged to criminalize are the ones deemed pivotal to most manifestations of organized crime, including illicit trafficking in firearms, namely:

The four Convention offences respond to the overarching objective outlined in the Convention. The objective is to disrupt criminal organizations and deprive them of their illicitly gained assets by targeting the associative element of organized crime and going after the leaders of such organizations and networks, as well as the single material offenders.

The offence of Participation in an Organized Criminal Group (Article 5), in particular, is very broad and far reaching, and allows the combination of conspiracy-based approaches that criminalize the mere fact of knowingly pertaining to such a group, or the more conservative approach of criminalizing the agreement to commit specific offences as part of such groups. Article 5 of UNTOC focuses on criminalization of participation in an organized criminal group. States are required to criminalize either or both sets of conduct specified in subparagraphs 1(a)(i) and (ii) of article 5 as crimes in their national laws, along with the related offences of aiding, abetting, organizing or directing such offences. These model legislative provisions include options for a conspiracy-type offence (that is, agreeing to commit a serious crime) and/or a participation-type offence (that is, actual participation in the activities of an organized criminal group). Broadly speaking, these two options reflect different common and civil law traditions. The offence of “conspiracy” was developed in common law countries. In many civil law countries, the concept of conspiracy is not recognized; the general position is that mere planning of an offence, without an overt act to put the plan into operation, is not criminal. Nonetheless, as the various examples of national laws noted below show, this distinction between the common law and civil law traditions is not absolute as some countries have laws that mix elements of conspiracy (agreement to commit) and association (taking part in activities) (UNODC, 2011).

Similarly, the Laundering of Proceeds of Crime Offence (Article 6, UNTOC) is crafted in a very broad concept of proceeds of crime. Defined in article 2 (e) as “any property derived from or obtained, directly or indirectly, through the commission of an offence”, it includes instrumentalities and other illicit assets. It also invites States parties to move away from the old list-based approach of predicate offences, and to apply the Proceeds of Crime offence to the widest range of predicate offences, at least to all Convention and Protocol offences, and to all serious crimes as defined by the Convention. If this is not possible, it should apply at least to a comprehensive range of offences associated with organized criminal groups (Article 6, 2, UNTOC). The provision is followed by a larger provision outlining specific measures to combat money-laundering which are also relevant to the offence of illicit trafficking in firearms.

The inclusion in article 8 of the offence of active and passive Corruption of (national, foreign and international) public officials in UNTOC recognizes that corruption of public officials is a very frequent lubricator of organized crime, through which criminal organizations achieve to infiltrate State institutions and gain control over them. With theft, diversion, and illicit trafficking of firearms, corruption often plays an important facilitating role that should not be underestimated. Soon after the adoption of UNTOC, Member States agreed on and adopted a dedicated UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in acknowledgment of the magnitude and importance of this offence and its cross-cutting nature that transcends the transnational organized crime context. As for the previous offence, the Convention also provides in its subsequent article 9 for specific measures to combat corruption (more details on UNCAC can be found in the E4J University Module Series on Anti-Corruption).

Finally, the offence of Obstruction of Justice (Article 23, UNTOC), aims at criminalizing acts such as the use of physical force, threat or intimidation, or the promise of such conducts. There is also the offering of an undue advantage to induce false testimony (para. 1(a)) or to interfere in the official duty of a law-enforcement or justice official (para. 1(b)), considered frequent impediments and obstacles to the criminal justice system. In countries, where most of the case evidence is built on testimonies, this offence is of particular detriment to the rule of law. This is particularly the case for serious and sensitive offences like organized crime and arms trafficking.

All these offences shall be established in the domestic law of each country “independently of the transnational nature or the involvement of an organized criminal group”, except to the extent to which article 5 would require such an involvement (Article 34, para. 2, UNTOC).

The Convention provisions, including its offences, shall be applied mutatis mutandis to its supplementary Protocols, and vice versa. All offences established under the Firearms Protocol shall be regarded as established in accordance with the Convention (Article 1 FP). In practical terms this means that all the Convention offences shall be applicable also to firearms specific offences, as the ones included in the Firearms Protocol.

In article 2 of UNTOC, the Convention defines serious crime, as “any offence punishable by national law with a maximum deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a more serious penalty”. In practice, not all firearms offences are punished under national law as serious crime since many countries consider firearms offences minor misdemeanors.

According to UNTOC (Article 3 (2)), a crime is considered transnational in nature if:

Finally, the Convention does not define organized crime, but requires the involvement of an organized criminal group, intended as:

One of the major problems that countries encounter when dealing with organized crime is to overcome the many obstacles that exist when dealing with different legal systems and jurisdictions. The main scope of the Convention is therefore to foresee a set of provisions and infrastructure that would help countries to more effectively and efficiently cooperate among them in order to “prevent, investigate and prosecute” the various forms of organized crime, including the offences foreseen in the Firearms Protocol.

The E4J University Module Series on Organized Crime addresses the issues related to the general application of UNTOC in greater depth. This Module will only refer to the specific provisions of the Convention that are relevant to the issue of illicit firearms and address its application to the specific context of firearms-related criminality.

As elaborated in Module 5 on International Legal Frameworks on Firearms, the Firearms Protocol supplements UNTOC and must be read in conjunction with its parent Convention. This means, in concrete terms, that the Convention provisions should apply, mutatis mutandis, also to the Protocol and its offences (Protocol, Article 1, paras 2 and 3), and that offences established pursuant to the Protocol are to be considered offences established under the Convention. This means that States must also criminalize the Convention offences and apply them to firearms-related offences.

National transposition of international obligations into domestic law improves and strengthens the criminal justice response to illicit firearms. The establishment of specific offences related to firearms and the determination of the penalties associated with them is a prerogative for each country.

However, offences established under the Protocol and its parent Convention, are neither exclusive nor exhaustive of all potential firearms offences. In practice, many national jurisdictions include a much broader spectrum of offences under the four above examined groups of firearms offences, as the below non-exhaustive table shows:

States may choose to legislate with respect to a broader range of weapons or adopt additional or more stringent measures to those provided by the Convention and Protocol to prevent and combat illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition and related transnational organized crime. It is important to bear in mind that any investigation, prosecution or other procedures outside the scope of the Convention or Protocol would not be covered by the various requirements to provide international cooperation (UNODC, 2011).