In order to understand the phenomenon of illegal exploitation of wild flora, it is important to understand the variety of actors involved as well as the range of opportunities that exist to commit crime or engage in corruption that are embedded in each step of the supply chain.

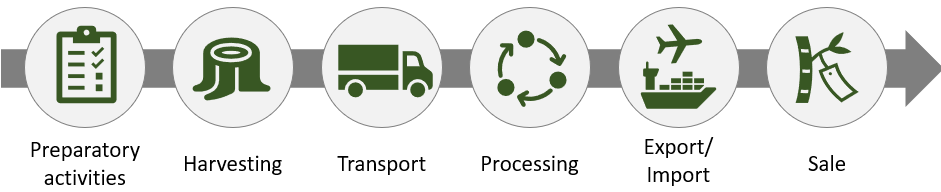

The following graphic shows the different stages of the supply chain of illegally exploited wild flora. It is important to note that figure 2 is a simplified version of the supply chain, as the specific steps will depend on the species being targeted, the location, the type of actors involved, etc. For example, when trafficking live specimens (i.e. cacti, orchids) there is no “processing” stage, as the live plants are transported directly from the harvesting point to the distributor or the consumer, whereas timber might undergo significant processing. At the same time, the supply chain is not as linear as depicted below and some steps might be repeated.

The stages of the supply chain of wild flora contain:

The illegal exploitation of wild flora includes a large spectrum of activities, with many different categories and types of actors involved. The actors engaging in burl poaching might be completely different from those engaging in charcoal or agarwood trafficking. Even when looking solely at one specific type of crime, such as illegal logging and timber trafficking, a diverse group of players and different levels of sophistication of operations can be distinguished, ranging from small-scale subsistence communities to large-scale corporations, elites and corrupt officials (Cao, 2018).

Phelps et al. (2016) distinguish between three key roles of actors along illegal wildlife supply chains: harvesters, intermediaries and consumers. For more information on the key actors, the structure of organized criminal groups as well as the involvement of corporations in wildlife crime, see ”Perpetrators and their networks” - module 1 of the UNODC Teaching Module Series on Wildlife Crime.

Along with key actors, other individuals and groups have peripheral duties that aid in the commission of crimes against wild flora, such as legal advisors, money exchangers and launderers, lawyers, notaries, document forgers, and financial counsellors (Levi et al., 2005; Kleemans, 2014; Boekhout van Solinge et al., 2016). In organized enterprises, security personnel may be hired from among policemen, military, criminals or armed groups to protect illegal operations (Boekhout van Solinge et al., 2016).

A case from the Brazilian Amazon (2008) is an example of the professionalism of some illegal timber networks and the widespread illegality in the sector. Hackers penetrated the computer system designed to monitor logging in the Brazilian state of Para. They were able to issue fake permits, which allowed loggers and logging companies to cut down and process much more timber than was officially allowed. Some 500,000 cubic meters of illegal timber was laundered by the hackers, a quantity which would require 14,000 trucks to transport it. At that time, over 300 timber companies were subject to investigations.

Each of the steps in the supply chain affords opportunities for crime and/or corruption in the exploitation of wild flora. Table 2 includes a list of examples of illicit activities, listed by the stage during which they may most likely occur. This list is not exhaustive, and some of the behaviours included may apply to more than one step (i.e. bribery, or forgery of permits and certificates).

Steps |

Crime and corruption opportunities |

|

Preparatory activities |

|

|

Harvest |

|

|

Transport |

|

|

Processing |

|

|

Import / Export |

|

|

Sale |

|

Corruption and related activities are a cross-cutting issue connected to the illegal exploitation of wild flora. While there is no universal definition of corruption, it can be broadly defined as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain” (Transparency International, n.d.). The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) recognizes corruption as an evolving phenomenon. While not providing a direct definition for corruption, the UNCAC lists agreed acts of corruption. For more on UNCAC and corruption, see Module Series on Anti-Corruption.

Corruption is an important issue in the illegal exploitation of wildlife in general, including wild flora. For an overview of the role that corruption plays in the trafficking of wildlife, and the regulations that aim to curb it, see Modules 1 and 2 of the Wildlife Crime Series.

The so-called “resource curse” is a phenomenon noted in economic and natural resources literature. It refers to the paradoxical situation in which countries that are rich in natural resources generally perform relatively poorly in economic terms. Resource-rich countries, on average, experience less economic development than countries without those resources: lower economic growth rates, lower levels of human development, and more inequality and poverty. The presence of many natural resources thus paradoxically appears to be detrimental to a country’s economic development. Corruption has been identified as the main reason why resource-rich countries often perform poorly economically. This is a particular phenomenon in the Global South.

In 2015, a panel of judges at the Jakarta Corruption Court in Indonesia sentenced a palm oil businessman to three years imprisonment and a fine of USD 7,700 for bribing a government official to obtain a land-conversion permit.

Over the course of the two-month trial, the evidence and witness testimonies confirmed that the businessman had bribed the governor to obtain land conversion permits for over 2,000 hectares, thereby violating Article 5 of the 1999 Corruption Law on bribery of state officials.

Several months later, in June 2015, the Bandung Corruption Court in West Java sentenced the government official to six years in prison and a fine amounting to USD 15,300.

In 2016, INTERPOL issued a Purple Notice concerning a newly discovered method to export illegally logged ipe trees (Tabebuia Serratiafolia). Ipe is a highly valuable timber species.

Investigations by Brazil’s Federal Police revealed that several timber companies used forged Forest Management Plans, which declared a much higher density or number of ipe trees in forest areas than can actually be found in the Amazon Rainforest. Corruption, particularly the combination of bribery with document fraud, was at the heart of the scheme. Ipe trees that were illegally logged in indigenous territories or national parks were marked as originating from legal harvest locations, effectively laundering them into the legal market.

Transparency International, a long-established NGO documenting patterns and levels of corruption worldwide, has long been monitoring corruption-related activities in the natural resource sector of Solomon Islands. Like many Pacific Islands, Solomon Islands has many natural resources, including timber, that are attractive to international trade. Many foreign-owned companies, especially from China, are involved in the exploitation of natural resources such that the financial gains are usually made abroad rather than in the countries of origin. Transparency International estimates that Pacific Island communities receive less than 12 per cent of the final value of the resources extracted.

The risk of corruption in all its forms is very high in the natural resource sector. Across the Pacific region, corporate entities as well as organised criminal groups use corrupt methods to exploit natural resources such as forests and fish stocks. Corruption also occurs in the mining sector, for instance in the exploitation of gold and manganese deposits. Common types of corruption involve active and passive bribery of officials working in forestry and fisheries departments or other environmental agencies, grand corruption involving high-level politicians and administrators, as well as private sector entities and individuals. In Solomon Islands, one of the largest exporters of tropical wood globally, many senior government leaders have held direct interests in logging concessions. There has been collusion between political leaders, public officials, and the timber industry. This is also documented in court cases implicating senior officials and politicians.

Transparency International’s uses the ‘Global Corruption Barometer’ to assess experiences with and attitudes towards corruption in the community using extensive surveys and questionnaires. In Solomon Islands, most respondents think that companies are corrupt (53 per cent) and use bribes or personal connections to secure profitable government contracts (60 per cent). Half of those surveyed (50 per cent) also believe that there is limited oversight of companies involved in the extraction of natural resources.

Transparency International also examines the measures taken by States to fight corruption and noted positively that a new Anti-Corruption Act was enacted in Solomon Islands in 2018 and that a new Act to protect whistle-blowers has also come into force. However, it also notes that key oversight bodies remain poorly resourced and filing and pursuing complaints pertaining to corruption is costly for ordinary people. Regarding the exploitation of natural resources in Solomon Islands, timber in particular, Transparency International has repeatedly stressed the need for adequate community consultation and due diligence before the government develops big projects or awards contracts and licences. This would help protect local communities from opaque deals, forced displacement, and a loss of livelihoods. The government must also ensure that safe, effective, and accessible channels are in place for communities to file complaints about abuses of power.

In 2008, a forestry officer from the Northern Region in Fiji was investigated for allegations of approving five letters of request from a logging contractor to delay the payment of outstanding royalties owed to landowners and the Government of Fiji, without the authority of the Conservator of Forests, and to continue logging and removing timber from its concessions.

The Fiji Independent Commission Against Corruption (FICAC) laid five charges of “abuse of office” in relation to these acts. The accused officer was found guilty of all five charges, and at a sentencing hearing in 2009 was fined FJD 1 500. FICAC appealed the decision based on the leniency of the fine, and at the appeal trial the fine was increased to FJD 20,000 with a default sentence of seven months imprisonment if not paid. In 2011, the High Court imposed the seven-month term of imprisonment for failure to pay the fine.

The level of planning and organization needed to commit many of the crimes against flora tends to be low when the origin and destination of the product are in geographically proximate; however, this can quickly change when operations expand. As they become more sophisticated, be it due to their size, the use of a number of middlemen or processing centres, the difficulty of concealing shipments or the need to cross international borders, among other reasons, offenders may form organized criminal groups to plan, execute, and/or launder the profits obtained. The level of organization of these groups, their operating practices, and the links to other crimes are heterogeneous and vary depending on a number of factors such as the type of product or the country in which they operate (Wyatt et al., 2020). Organized criminal groups tend to use already established routes and networks to smuggle not only a variety of species, but also other products such as weapons, drugs, and even people (Pires and Moreto, 2016; INTERPOL, 2020). For more details on the participation of organized criminal groups in wildlife trafficking, see Module 1 of the Wildlife Crime Series.

In the case of flora, the involvement of organized criminal groups in the trafficking of timber is well documented, although it depends on the type of illegal logging. Some activities under the categories of illegal forest conversion and other illegal forest activities may be considered organized crime, as they feature the involvement of corrupt officials, illegal entrepreneurs, armed groups and large corporations (Boekhout van Solinge, 2014; Boekhout van Solinge et al., 2016). Informal logging typically involves mainly small-scale producers rather than organized criminal groups (Pokorny et al., 2016).

Possible differences between the illegal timber and non-timber flora trade are that large players and networks seem to dominate the former (Dauvergne and Lister, 2011), as well as the fact that timber tends to be trafficked in huge volumes. Although the involvement of organized criminal groups in dealing in non-timber flora products is less well understood, there are some examples of the participation of these groups in the poaching and trafficking of other flora. In Madagascar, buying vanilla has been recorded as a method of laundering proceeds of timber trafficking (see Example: Violence and crime convergence of vanilla cultivation in Madagascar). While the participation of organized criminal groups in orchid trafficking has not officially been established, the volume of the trade and the fact that it moves millions of plants all over the word, through a variety of platforms, could indicate some level of organization (see also Phelps and Webb, 2015).