This section discusses approaches that incentivize conservation and reduce wildlife trafficking. Eco-tourism and trophy hunting are the most well-known approaches. Yet, the sustainability of such approaches is under scrutiny after climate change related disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic have left many operations that rely on international travel in tatters. There are other approaches and models that provide indirect and structural incentives for communities to support conservation while providing for sustainable livelihoods. Roe and colleagues provide a typology according to which they group community conservation and sustainable livelihood approaches. In borrowing from their typology, the following models are discussed in this section: approaches that directly and indirectly incentivize conservation and models that incentivize alternative livelihoods.

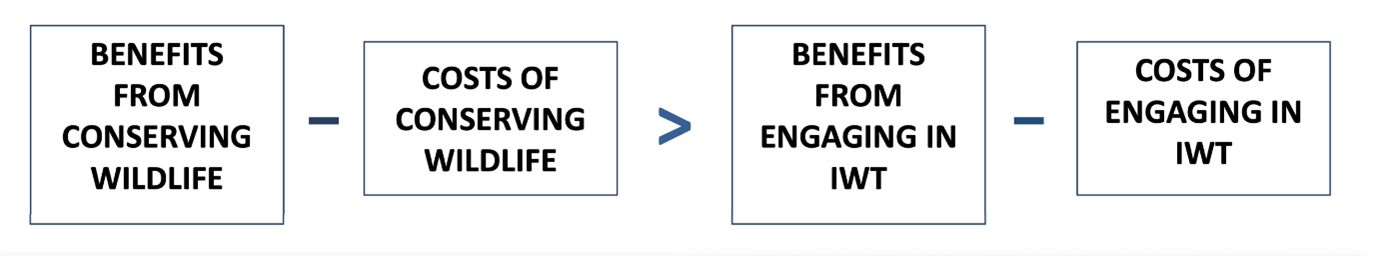

Beyond involving communities as crime preventers and crime fighters in law enforcement efforts as discussed above, another key strategy is to increase the incentives for IPLCs to actively engage in conservation. According to the Poachers to Protectors basic equation framework, community-centred conservation is about increasing the benefits from conservation. This framework of Local Communities as First Line of Defence (FLoD) in combating wildlife trafficking (known in the equation as “Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT)”) offers pathways aimed at meaningful engagement of IPLCs. The theory of change is based on a simple equation:

Much of the policy and practice work in this area is aimed at rehabilitating displaced or evicted communities and former poachers. Many projects focus on alternative sustainable livelihoods, compensations and to some extent, albeit rare, ownership or rights over land and resources. Based on these variables, the way forward is rather complex and might not always be in sync with communities’ organic needs, wants, or historical practices. For example, compensation, which has emerged as a prospective strategy for mitigating the negative impacts of conservation projects on rural communities, has a high potential for abuse, and can also give rise to concerns about environmental and social justice if not properly addressed.

Eco-tourism and trophy hunting are the best-known and most popular approaches to directly incentivize conservation by communities. While both have been on the receiving end of criticism, including due to the carbon footprint of international travel, the underlying logic is to render wildlife valuable to community landowners and users. The revenue is usually self-generated at local level through the sustainable use of protected species. While the approaches are usually not reliant on external funding (other than consumers paying for tourism and hunts), they do depend on access to external markets, technical skills and advice and partnerships with external organizations. Tourism, however, is highly sensitive to external shocks, e.g. disease outbreaks (Ebola, COVID-19, etc.), terrorist attacks, internal strife or the holding of elections. In addition, corruption, elite capture, nepotism, discrimination on grounds of class, gender, race, caste and ethnicity are factors that appear in these approaches that can have negative implications for IPLCs.

Community participation in conservation initiatives has taken many forms, ranging from comprehensive community-centred approaches where management responsibilities and property rights are devolved to communities to short-term interventions with little measurable impact. The Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) in Zimbabwe and community conservancies in Namibia are amongst the most famous CBNRM initiatives. While the former provided the blueprint for similar programmes across southern Africa, the latter has been lauded as one of the most successful models of community-based conservation worldwide. Both interventions are discussed below.

The CAMPFIRE programme was conceived shortly after Zimbabwe attained independence in 1980. Black people had lost land and property rights during the colonial regime. In the post-independence era, land reform emerged as a major political and economic issue. Within this context, the overarching goal of CAMPFIRE was to share the benefits generated by the wildlife economy with local communities, in the process ensuring that wildlife conservation remained a viable income-generating option. It was envisaged that benefit-sharing would be achieved by devolving property rights and management to rural district councils (RDCs) and not the communities themselves. Foreign donor agencies provided start-up capital for basic infrastructure, project development and administration and continued to do so until the country’s economic disintegration in the early 2000s.

RDCs, on behalf of communities on communal land, are granted the authority to market access to wildlife in their district to safari operators. In turn, safari operators sell hunting and photographic safaris to mostly-foreign sport hunters and eco-tourists. The RDCs are required to pay the communities a dividend of no less than 50 percent of the income from these sources.

CAMPFIRE stood out in its time due to a combination of factors:

CAMPFIRE has had successes and challenges. The direct benefits derived from sustainable wildlife use, which includes safari hunting, game cropping, photographic safari drives and other ecotourism ventures. Although communities receive a share of these revenues, they have no equity in wildlife utilization (Murombedzi 1999: 289). International and local tourism companies, hunting operators and ancillary services are the main beneficiaries.

CAMPFIRE generated more than US$20 million in transfers to the participating communities between 1989 and 2001 (Gandiwa, Machena, and Mwakiwa 2017), with revenue from safari hunting and ecotourism being the main income streams. The amount disbursed to communities was 52 percent of the total income earned. Sports hunters and eco-tourists would buy game and trophy hunts; the RDCs, in turn, would then pay out dividends to communities based on an agreed formula. There were, however, underpayments and delays in processing payments (CAMPFIRE n.d.). By 2017 there were 120 Campfire Committees, potentially reaching 200 000 households in 58 districts, working in association with Ward Committees and traditional authorities. Of those 58 districts, 15 are considered to have sufficient wildlife to generate financial benefit to communities.

When the United States banned the importation of elephant and lion trophies in 2014, there was an immediate impact on income generation at CAMPFIRE sites. In 2013, annual revenue was US$2.3 million, and by 2016-17, this had dropped to US$1.7 million (Gandiwa, Machena, and Mwakiwa 2017).

Outside the cash benefits, there were other benefits such as employment opportunities and bushmeat provision, subsidised tillage, and drought relief and some indirect benefits such as infrastructural facilities. Tchakatumba and colleagues note that the percentage of households that never benefited from CAMPFIRE employment opportunities - either on full- or part-time basis - was high, while little had been done for building or maintaining clinics, roads, and boreholes.

Where information is available, the impact on wildlife (primarily measured by reference to elephants, the dominant ‘charismatic’ hunted species across the CAMPFIRE areas) is patchy. Wildlife habitats are well maintained in CAMPFIRE areas and this has created conditions for increased wildlife populations outside protected areas (Gandiwa, Machena, and Mwakiwa 2017). Where resources have been sufficient and focused on collaboration with safari operators, there have been notable gains: in Dande, poaching of elephants declined from 40 in 2010 to 5 in 2017. In the Hwange district, however, uncontrolled migration of elephants through the 18 wards of the communal area had caused serious conflict with humans (CAMPFIRE n.d.).

Namibia is known for its community conservancies, which employ, among others, former poachers and community members as wildlife guardians. These community conservancies are self-governing democratic entities, run by local people, with fixed boundaries that are agreed on with adjacent conservancies, communities or landowners (Namibian Association of Community Based Natural Resource Management 2020). The Namibian case provides useful insights as to what works and what does not work in terms of the marketization of conservation. All of the features listed above in relation to the original CAMPFIRE model could be repeated word for word to describe the Namibian Communal Conservancies. Also analogous is their very wide geographic spread across the country and the economic centrality, in both the Zimbabwean and Namibian models, of ‘charismatic’ large African mammals (‘big game’).

In Namibia, all communal land is owned by the state, but the Communal Land Reform Act 5 of 2002 allows for group tenure rights by registration; traditional authorities, where operative, also have a recognized role. Deriving from this legislation, Communal Conservancies and Community Forests are self-governing entities. The Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) is responsible for broad oversight and has Standard Operation Procedures on the essentials of governance, with key compliance requirements. With the facilitation and assistance of Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO) and regional staff from conservation support organisations, the MET carries out annual audits to assess conservancy governance and financial and natural resource management performance. Funding derives from donations (mostly international), fees from joint venture tourism and ‘conservation hunting’ and payments from ecological services (PES). Of the 87 conservancies, 56 have ‘conservation hunting’ concessions. The aim is for all 87 conservancies to become financially sustainable and effectively self-governing. Nearly half were regarded as financially sustainable before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-21, but there are others with relatively poor natural resources that will probably need long-term support.

The Community Conservation Trust Fund was established and registered in 2017. It was designed to be an endowment fund, assisting where necessary with operating costs and minimum support packages. The funds in the Trust come from investments and continued donor support based upon conservation performance. As conservancies mature, they are investing more in alternative livelihoods and education.

The impacts on wildlife have been notable. Elephants have increased from roughly 7,500 in 1995 to more than 20,000 individuals by 2016 (Republic of Namibia 2016). Lions have expanded their range from Etosha National Park westwards to the Skeleton Coast and are increasing in the north-eastern regions. Namibia also boasts the largest population of free-ranging black rhino in the world. After an increase in elephant and rhino poaching between 2014 and 2016, rhino poaching decreased from 100 (2015) to 49 in 2019. There have been livestock attacks (mostly by hyena and cheetahs) and crop damage (by elephants) but affected parties have been compensated from a national fund and individual conservancies. More than 212,000 people were living in the 87 conservancies by 2020. They were benefitting from:

Total cash and indirect benefits increased from less than NAD 1 million (1998) to NAD 147 million (2018).

Namibia’s conservancy programme is not without its challenges, however. For one, it is alleged that accountability and transparency among some conservancy committees are not always present. A form of elitism is also preventing bottom-up consultations on important decisions in some conservancies, on the basis of who has an influential voice (Beckert 2013: 89-90). In other instances, old elite interests – legitimate or otherwise – that were threatened by the establishment of conservancies and the empowerment of local people, have opposed and derailed efforts (IRNDC 2011). In some instances, input and advice from community elders and traditional leaders have not been taken onboard. There has been a high turnover in conservancy committees, with some members not originating from or living in the conservancies they represent. Allegations of nepotism and corruption have also arisen. Furthermore, some conservancies are on marginal land that has limited or no potential for tourism or other uses, and these offer little prospect for income generation. There have also been reports that benefits from the conservancy programme do not always reach the most needy and marginalized, namely women, youth and the elderly. Overall, taking into account such challenges, the Namibian conservancies appear to be working sustainably in the interests of both wildlife and humans.

Formed in 1991, the International Gorilla Conservation Programme’s aim is to ensure conservation of mountain gorillas and their habitat in Rwanda, Uganda and Democratic Republic of Congo. It has the twin objectives of reducing threats to mountain gorillas and their forest habitat by creating widespread support for conservation among local communities, interest groups and the general public, as well as improving the protection of gorillas and their habitat by encouraging the relevant authorities to adopt a consistent, collaborative approach to conservation policy. By improving livelihoods, encouraging sustainable use of resources and tackling other local issues via a range of community initiatives, the programme aims to influence attitudes to conservation at all levels and reduce the threats facing the parks, forests and wildlife.

Case study based on http://igcp.org/about/

The Maasai Wilderness Trust is a US-based NGO. Kuku Group Ranch is Maasai-owned, one of a number of ‘group ranches’ in the area between Maasai Mara and Amboseli National Parks in Kenya, a major wild-life corridor as well as an area of traditional Maasai cattle-farming. The Ranch is a partnership between professional conservationists and Maasai leaders. In this model, government is supportive but at a distance, apart from the regular provision of schools and clinics. Two forms of local governance – professional/commercial and traditional – exist within the same physical area on the basis of a clear understanding of their respective roles.

It provides some direct formal employment; develops locally based livelihoods, particularly for women; improves local health and education and effectively manages natural resources, including sought-after wildlife. The revenue stream from an eco-lodge partly supports a variety of initiatives. There is a grassland restoration programme and some alternative sources of income: a grass-seed bank, beading, and beekeeping and honey production. There has been a 50 percent decrease in wildlife poaching since 2015 in the Ranch area.

With regards to impacts on people, more than 300 people have found employment; over 9,000 school children are supported; more than 17,000 patients treated; traditional grazing practices and grasslands improved and verified compensation paid for stock losses to predators.

Natural resource development can impact wildlife populations (through encroachment, pollution and culling) and the livelihood strategies of IPLCs. Although portrayed as offering opportunities for socio-economic development and social upward mobility to IPLCs, large-scale mining or oil and gas development projects seldom offer transformative effects to locals. While there may be short-term gains, such as contractual labour opportunities, IPLCs may be left with long-terms negative environmental impacts including air, water and soil pollution and depleted wildlife numbers. Such projects may also involve encroachment into wilderness areas and landscape fragmentation, not only by way of exploration but also through infrastructure developments such as railways and roads. While these developments can facilitate transportation and connection between rural areas and urban centres, they also affect wildlife, which can be relegated to smaller areas for habitat or away from usual feeding and breeding grounds. These impacts on wildlife can also affect IPLCs, who may rely on wildlife for their livelihoods. Infrastructure development can also provide easier access to would-be poachers and traffickers.

Once numbering in the millions, barren-ground caribou populations have dropped by over 70 percent since the early 2000s (Parlee, Sandlos, and Natcher 2018). Caribou play an important role in arctic/subarctic ecosystems, and, in northern Canadian Indigenous cultures, also in economies and health. The efforts to stop the barren-ground caribou population decline have mostly focused on supressing subsistence harvesting by Indigenous peoples (Parlee, Sandlos and Netcher 2018). Using 13 years of harvest data and qualitative research on adaptive practices, Parlee, Sandlos and Natcher (2018) show that subsistence harvesting was not a threat to the sustainability of barren-ground caribou. Rather, the data show that Indigenous communities have developed social rules that prevent unsustainable use, such as by reducing the harvest of caribou in favour of other species during a period of caribou decline.

The study by Parlee et al. (2018) also shows that mining activities have a significant impact on caribou numbers and livelihoods of IPLCs. Mining activities create habitat fragmentation affecting migration routes and create stresses of noise, dust and habitat degradation (Parlee, Sandlos and Netcher 2018). Indigenous groups recognised the harmful consequences of mining activities and took legal action against the Yukon (provincial) government when it made a decision to increase mining in the largely undisturbed Porcupine caribou range despite the Peel Watershed Planning Commission’s recommendation to protect 80 percent of the area from development (Hong 2007; Parlee, Sandlos and Netcher 2018). The case made it all the way to the Canadian Supreme Court, where the court ruled that the Yukon government did not have authority to make changes to the recommendation plan of the Commission (Hong 2017).

The Irulas have been praised as ‘the skilled snake catchers’ of India (Venkatraman 2018). Historically, the Irulas were hunting snakes and rats at farmers’ requests; however, due to modernisation, declining snake populations and a ban on hunting and sale of snake skins by the Government of India in 1970s, the Irulas had to adapt. Some members of the Irula tribe use their expert knowledge and understanding of snakes to, for example, work for the Irula Snake-Catchers Cooperative to capture poisonous snakes to create anti-venom (Venkatraman 2018). Six companies produce around 1.5 million anti-venom vials a year, the majority of which is created from the venom gathered by the Irulas (Sampathkumar 2018). It has been argued that presence of the Cooperative ‘provided legitimacy’ to Indigenous knowledge and skillsets, because as ‘hunter-gatherers’ the Irulas were considered poachers by local government officials’ (Sampathkumar 2018). Two members of the Irula tribe were also invited to help catch pythons in Florida (USA), which are a threat to biodiversity in the Florida Everglades National Park (Biswas 2017). Over the course of two months, they captured 34 pythons (Sampathkumar 2018), emphasizing how their traditional skills can be useful in other settings.

Bans might seem like an obvious answer to poaching and illegal wildlife trade; however, they do not account for unique local circumstances (Duffy 2010). Additionally, they can further sustain inequalities between the traditional countries of supply and demand (Duffy 2010; Hübschle, Mackenzie, and Yates 2020). Perhaps the most prominent example of this is the CITES ban on trading in ivory. Prominent Western NGOs and states campaigned to ban the trade in ivory and save elephants, but in the process of doing so simplified the issue and did not adequately portray the complex issues that local communities face living with elephants (Duffy 2010). Southern African states resisted the ban and argued that the trade in ivory could actually save the elephants, generate revenues for conservation and facilitate CBNRM programmes (Duffy 2010). CITES banned the international commercial trade in ivory in 1989, and has been criticized for reflecting the preferences of ‘powerful elite factions in the northern hemisphere’ that do not bear the cost of living with or nearby the wildlife (Hübschle, Mackenzie, and Yates 2020: 429).

The ivory ban sparked a larger debate in the late 1990s and early 2000s of which conservation paradigm – sustainable use or preservation – CITES should follow (Hübschle, Mackenzie, and Yates 2020). Many countries in southern Africa support the sustainable use of wildlife in conservation projects, as this would provide incentives for local stakeholders to protect wildlife. Still, in its listings, CITES mostly focuses on the level of imperilment of endangered species at global level rather than population numbers in individual states. Individual countries might be teeming with wildlife, but trade might still be banned because species conservation is doing less well in other jurisdictions (Hübschle, Mackenzie, and Yates 2020).

What trade should be allowed is a key question in conservation circles. Commercial breeding has been suggested as one way to keep pressure off the animal populations in the wild. In order to achieve good outcomes for endangered species conservation, a specific set of criteria needs to be met (Tensen 2016). A ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution is unlikely to stop illegal wildlife trade as local contexts matter. Below are several case studies that show successful wildlife trade projects that led to a reduction of illegal wildlife trade while supporting IPLCs.

The vicuña species were once on the brink of extinction due to overhunting. Nowadays, they are thriving once again in the Andean region (Kasterine and Lichtenstein 2018). The Vicuña Convention of 1969 prohibited vicuña hunting and introduced a CITES trade ban on the export of vicuña pelts (which was lifted in 1994). Despite the ban, the Peruvian government shifted from a prohibition-based system to trade system in 1980. Changes were made to the local vicuña management policy and local communities were given rights to shear the fibre of vicuñas (Kasterine and Lichtenstein 2018). Following strict guidelines, local communities started to capture and shear vicuñas for buyers. Vicuña fibre is a valuable commodity and occupies ‘an exclusive position in the luxury fashion market’ (Kasterine and Lichtenstein 2018: 7). This resulted in ‘a dramatic recovery’ in species numbers due to communities now having ‘an economic stake’ in the vicuñas’ survival (Kasterine and Lichtenstein, 2018: ix). For instance, it was estimated that Peru had 10,000 vicuñas in 1969; in 1981 the numbers had increased to 61,900 and to 208,899 by 2012 (Kasterine and Lichtenstein 2018). Between 2013 and 2017, Peru also reported a 29 percent increase in the collected fibre. Although many challenges still remain, including some poaching, the impact of climate change and the deterioration of grasslands due to overgrazing by domestic animals (Kasterine and Lichtenstein 2018), overall ‘poaching levels dropped dramatically’ due to local management initiatives and trade regulations’ (Lichtenstein 2015: 39).

The American crocodile has been the subject of overexploitation for its skin and meat. The effects of overexploitation were felt severely in Colombia. Between 1928 and 1932, an estimated 700,000 to 800,000 crocodiles were slaughtered to meet the demand for skin. Consequently, the most conspicuous species in Colombia’s mangrove ecosystems, the American crocodile was almost eliminated from its natural habitat, which was (and continues to be) degraded and destroyed by coastal development, making natural recovery of the species difficult. Populations became restricted to small, isolated pockets of suitable habitat, such as within the mangrove ecosystems in the upper and middle reaches of the Magdalena River and the Bay of Cispatá, which is a protected area that provides ideal habitat for the American crocodile.

To protect the species, the American crocodile was included in CITES Appendix I and the Colombian government banned hunting. Illegal trade in crocodilian skin and meat continued, however. To address the issue of population decimation, new conservation initiatives and incentives were proposed including the establishment of the ASOCAIMAN cooperative. The cooperative manages the local population of American crocodile in Bay of Cispatá, Colombia via egg harvesting and re-release of juveniles (Roe and Booker 2019). It was hoped that these activities would contribute towards moving the species from CITES Appendix I to Appendix II and potentially resuming trade in crocodile skins (Roe and Booker 2019).

Support for community development and empowerment lies at the heart of the initiative. As part of this initiative, a group of 15 “caimaneros” or former crocodile hunters were trained to become skilled managers of the crocodile and effective conservationists, which has also decreased incidents of poaching. There has been an almost 200 percent increase of the crocodile population in the Bay of Cispatá and 9000 American crocodiles have been released into the wild. Due to the success of the ASOCAIMAN initiative, in 2016 the Cispatá population of American crocodile was moved to CITES Appendix II.

Rising demand for luxury wildlife products such as caviar is one of the main drivers of the illegal wildlife trade in pickled sturgeon roe. All 27 species of sturgeon are included in the IUCN Red List (Musing et al. 2018). There have been calls to completely ban the caviar trade to facilitate the recovery of the species; however, the trade is an important income for certain areas, such as the Caspian Sea region, and a complete ban would punish legitimate producers (Duffy 2010). Trade of sturgeons and associated products has been regulated under CITES since 1998 and several countries, such as Romania, have introduced a ban on sturgeon fishing (EUMOFA 2018).

Through several regulatory changes, the caviar industry has changed and moved from wild-caught to captive-bred caviar. Nowadays, it has been estimated that nearly all (EUMOFA 2018) or 95 percent of all legal caviar trade (Musing et al. 2018) comes from farmed sturgeon. This shift to farmed sturgeon and caviar production has been seen as ‘having brought illegal caviar trade under control in the EU’ (Dickson 2020). Nevertheless, the move to captive-bred caviar has created other challenges, such as a caviar grey market in Europe where captive-bred caviar production has been exploited to facilitate illicit caviar trade and has caused a loss of livelihood for sturgeon fishing communities in Europe (Dickinson, 2020).

Operating primarily in Indonesian Borneo (West Kalimantan), Yayasam Planet Indonesia is a village-led conservation project facilitated by a US-based NGO. Started in 2014, the project combines the sustainable management of endangered species (orangutan, a variety of birds, rare woods) with agricultural and fisheries management and carbon sequestration through forest conservation.

Two-thirds of Indonesia’s poor live in or around forest; deforestation and impoverished soil impacts local livelihoods as well as globally important biodiversity. A 2012 Constitutional Court decision, and subsequent ministerial regulations in late 2014, oblige local governments to reallocate 12.7 million hectares of state forest to poor indigenous communities. The programme takes a ‘rights-based approach to conservation’, noting that ‘local problems need the expertise of local people’. The objective of the programme is ‘to manage local biodiversity while improving human well-being:’ this includes developing sustainable agriculture programmes in the buffer zone (organic farming, reforestation, sustainable fisheries management) in order to provide effective alternatives to forest clearing, soil degradation, exhaustion of valuable timber, trade in orangutans and other wildlife. The local governance vehicle for this process is ‘Conservation Cooperatives’, voluntary self-governing structures. These cooperatives are the access point for:

There is also an education programme, including adult literacy and the support of local state schools, and a health programme in cooperation with state-supported clinics. In collaboration with NGOs Oceanwise and Blue Forest, the model has been extended to include a local fishing community and the linked conservation of coastal mangrove swamps.

Case study based on https://www.planetindonesia.org

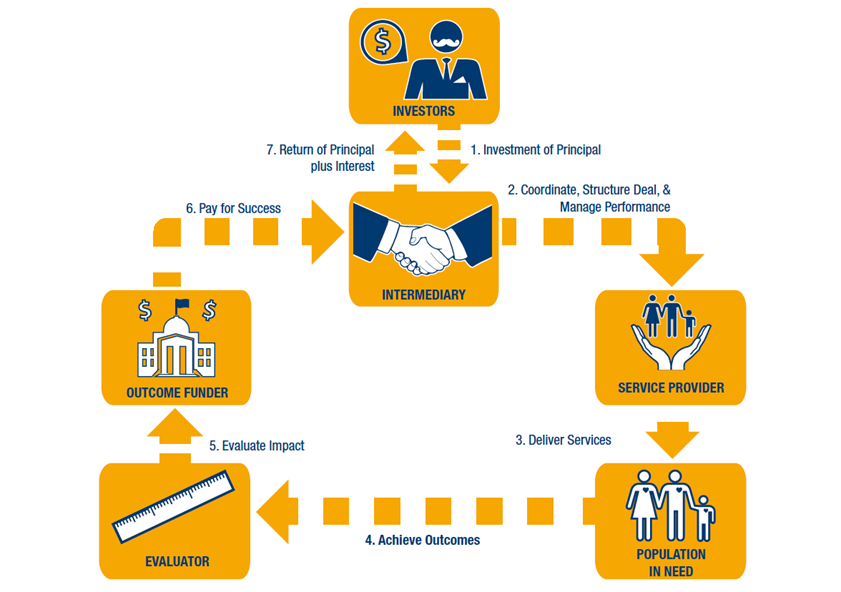

The notion of introducing Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) to protect wildlife and provide income to communities has been a matter of debate for several years. SIBs and the related development bonds expose private investors to social projects. Also known as ‘pay for success financing’, Gustaffson-Wright and colleagues (2015: 2) define SIBs as a “financing mechanism that harnesses private capital for social services and encourages outcome achievement by making repayment contingent upon success.” The financing mechanism has become popular in development circles as it provides an additional vehicle for public-private partnerships through which more money is channelled into social programming. Due to its outcome-based orientation, data collection and impact measurement are integral to project development and implementation (Malan, n.d.). Associated with highly contentious and somewhat complicated areas of social policy such as offender rehabilitation, early childhood development and youth programmes and homelessness, SIBs have been suggested as a possible community incentive scheme for wildlife conservation.

The rationale behind SIBs is akin to payment-by-results schemes associated with target-based performance management. The linking of contracts to specific outcomes encourages goal clarity and provides organisational leaders with the leverage required to focus on key areas of activity (see Figure 6). Impact investment focuses on outcomes, which is a move away from traditional financing which focuses on service delivery; it has been suggested that impact investment motivates people on the ground to achieve the results (Crone 2020).

The financialization of social services raises important questions as to whether private returns might trump social outcomes. This includes questions as to which populations are most likely to benefit from SIBs, the transaction costs associated with programme design, budget liability and risk and the potential stifling of programme innovation to ensure continued private returns (Warner 2013). The same critique applies to the payment for ecosystem services paradigm. It is important to be aware of a possible conflict of interest: do market forces and profit motivation allow room for benign and altruistic social outcomes in an uncertain economic environment? And should public service provision be exposed to the vagaries of the market? (McHugh et al. 2013).

It has been argued that SIBs might provide new and additional resources to finance social services in local communities living near protected areas. As shown in the earlier case studies, any projects at grassroots level need to give a voice to those most affected or targeted by projects and interventions. Natasha Anderson (IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group Meeting 2013) suggests rhino production incentives for communities based on the balance between rhino births and deaths. If there were minimal rhino deaths in the target area protected by a specific community – e.g. only one mortality for ten new-born rhinos – then social incentives such as schools or cash money could be made available to communities. The incentive structure would work on a sliding scale : the more rhino deaths, the less funding available for the chosen social goal set by the community. The approach is not fool-proof and questions of conflict-of-interest and the monetization and financialization of conservation outcomes arise. Moreover, there may well be issues around the long-term sustainability and success rate of SIBs.

The Rhino Impact Investment (RII) Project is an initiative of United for Wildlife, a partnership between seven of the world’s leading wildlife charities and The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. It is a pay-for-results approach to conservation, as noted above, moving from traditional sources of funding to ‘an outcomes-based financing mechanism’ (Withers et al. 2018). The funds are directed towards selected sites in Kenya and South Africa and a set of key performance indicators, such as net rhino growth rate, are used to assess the conservation outcome (Withers et al. 2018). The USD 50 million Rhino Impact Bond is looking to increase the global black rhino population by ten percent (Srivastava 2019). Based on the conservation outcome, the outcomes-payer will pay the investor the original investment plus or minus a percentage according to conservation outcome (Withers et al. 2018).

A buffer zone serves the purpose of enhancing the insulation of protected areas “from potentially damaging external influences, and particularly those caused by inappropriate forms of land use” (Bennett and Mulongoy 2006: 7). The buffer zone of a protected area may be situated around the periphery of a protected area or it may connect two or more protected areas. The concept of buffer zones in conservation was initially proposed in the 1930s but became an integral part of the management approach in UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere Programme in the 1970s (UNESCO 1974). The Biosphere concept encapsulated a two-tier hierarchy for buffering protected areas: a “buffer zone” where land use would be limited to activities that were compatible with the core conservation area and a “transition zone” where sustainable use areas could be developed (Bennett and Mulongoy 2006).

The main objective of a buffer zone is to provide an additional layer of protection to a World Heritage site. In the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention of 2005, the inclusion of a buffer zone into a nomination of a site to the World Heritage List is strongly recommended but not mandatory (International Expert Meeting on World Heritage and buffer zones 2008). While ecological and biological concerns have driven the design for buffer zones, they are presented as a means to strengthen local land and resource claims (Neumann 1997). Buffer zones are also seen as a way to bolster indigenous land ownership and natural resource user rights. Although local participation and benefit sharing is encouraged on paper in buffer zones, the approach has faced many challenges as its design and function in practice are not straight-forward.

Buffer zones may home protected species, so restrictions on human activities still apply and human-wildlife-conflicts may still occur, which imposes costs on landowners and users (Bennett and Mulongoy 2006). Critics argue that buffer zones were similar to fortress-style conservation practices, as reports of forced relocation, restriction on access to resources, abuses of power by conservation authorities and increased government surveillance were the order of the early days (Neumann 1997). Moreover, it was external NGO advisers and scientists, not the affected local communities or indigenous peoples, who would often decide which forms of land use were deemed acceptable in buffer-zones.

The early history of the management of protected areas in Nepal was based on the principles of fortress conservation, including the forceful eviction of indigenous peoples and protectionist conservation management policies. A 2009 study commissioned by Transparency International Nepal found a legacy of antagonism between people living near parks and the park authorities (Bhuju, Aryal, and Aryal 2009). Against this backdrop of community-conservation tensions and in the aftermath of the civil war, Nepalese conservation authorities reached out to local communities to get them actively involved in wildlife protection.

Community forestry is a participatory forest management system in Nepal that was started in the late 1970s. It provides rural communities with control over management and protection of forest resources. The ‘fences and fines’ approach to conservation management was supplemented with incentive measures, such as legally sanctioned removal of thatching grass, the creation of buffer zones and revenue-sharing schemes (Shova and Hubacek 2011).

Nepal’s Buffer Zone Management Regulation of 1996 granted rights to local communities to manage and use natural resources within those zones. Local people were able to choose which development activities to become involved in through a buffer-zone management committee, which consisted of elected representatives of the community (Bhattarai et al. 2017). Nepal’s policies emphasize the importance of implementing a process that allows communities to choose activities according to their priorities rather than defining outcomes (Allendorf and Gurung 2016). Development activities in buffer zones were mostly focused on infrastructure development such as the construction of buildings, roads, communication (telephone installation), irrigation and water infrastructure and ablution facilities (Allendorf and Gurung 2016). In 2009, an instrument that provided for the payment of compensation to communities for livestock losses was also established. Conservation agencies have worked with local communities on innovative measures to reduce the incidence of human-wildlife conflict, including the construction of trenches, electric fencing and watchtowers, and the supply of torches and binoculars (Aryal et al. 2017). In addition, the park authorities share about a third of the park’s revenue with communities that live adjacent to protected areas.

These various measures for achieving a rapprochement between the local communities and the authorities seem to have achieved some success. A study comparing local residents’ perceptions of benefits and losses associated with protected areas in India and Nepal found they were more favourably inclined to protected areas in Nepal. The researchers attributed the greater enthusiasm to Nepal’s status as a wildlife tourism destination and its track record of successfully involving local communities through benefit sharing (Karanth and Nepal 2012). At the same time, however, Nepal has also adopted tougher penalties for wildlife crimes. Wildlife authorities are afforded special judicial powers, including the right to issue fines and detain those suspected of wildlife crime (Aryal et al. 2017). Other studies have cast doubt as to whether law-enforcement agencies and security personnel have contributed much to lowering poaching levels in Nepal (Dongol and Heinen 2012). Either way, the country’s renewed focus on involving local communities in conservation management, enforcement and revenue sharing is laudable and appears to have made some measurable difference.

While there are certainly global lessons to be learnt from the Nepalese case, it should not be construed as a perfect model for conservation, especially since grand and petty forms of corruption are pervasive and the country’s human rights record is less than desirable. What is remarkable about the Nepalese conservation regime, however, is that the conservation authority is open to learning and incorporating new ideas.

Alternative livelihood projects aim to reduce activities that have a negative impact on the environment by substituting them with other activities that provide equivalent, if not higher, benefits (Wright et al. 2016). Additionally, these alternatives can involve activities that do not involve exploitation of biodiversity (LeClerq et al. 2019). There is not a single, common definition of what an “alternative livelihood” project is, however. Generally, their main objective is to achieve biodiversity conservation by providing a less harmful alternative to a livelihood that is damaging ‘a biodiversity target;’ this is done by either providing an alternative resource to the one that is being used or by providing an alternative occupation or method of resource utilization that is less damaging (Roe et al. 2015).

Despite these efforts, studies have shown that there is insufficient evidence of how successful alternative livelihood projects are in terms of conservation. Wicander and Coad (2018: 451) used 19 case studies to assess the effectiveness of alternative livelihood projects created to substitute for hunting wild meat in West and Central Africa, and found that projects’ “outcome monitoring was lacking or that data had not been analysed” due to time and budget constraints. Similarly, study by Roe et al. (2015) looked at 106 projects, of which only 22 had provided a measure of conservation effectiveness. The Roe study was motivated by a concern that considerable amounts of conservation funding are allocated to alternative livelihood projects despite there being little evidence of conservation impacts (Roe et al. 2015: Discussion).

Additionally, there have been studies exploring how well local populations understand the conservation objectives of alternative livelihood programmes. A study conducted in Bardia National Park, Nepal, found that local people who participated in alternative livelihood training that was focused on sewing and tailoring in addition to alternative forest use, but were not inherently connected to conservation, tended not to internalize the conservation objective of the training (LeClerq et al. 2019). The study also noted that people involved in alternative livelihood activities which were not directly related to a biodiversity target did not perceive a connection between the training and the use of a specific resource (LeClerq et al. 2019). This disconnect can potentially affect the long-term success of alternative livelihood programmes. This study suggests that it is important that alternative activities and incentive-based programme benefits are consciously linked by local residents to conservation objectives to ensure a long-term commitment to conservation (Nepal and Spiteri 2011; LeClerq et al. 2019).

Almost 50 percent of the world’s cocaine supply derives from coca bushes that grow in protected areas or indigenous territories in Colombia (GPDPD.org), and coca cultivation has been linked to increasing deforestation (Dávalos et al. 2011). Drivers of deforestation in Colombia include armed conflict driving growers away from their existing crops; higher income from coca attracting new growers and encouraging existing growers to expand; eradication and law enforcement force growers to move to other areas; and eradication efforts, which may contribute to deforestation directly (Dávalos et al. 2011). Germany’s Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) together with partner countries such as Thailand, Colombia and Peru, advocates for an alternative pathway to tackle the international drug problem and linked deforestation by advocating for creation of alternative development opportunities (BMZ.de). For many families and communities in Colombia’s coca-growing regions, coca cultivation is the main – and sometimes only - opportunity to generate income. These regions often lack security, infrastructure and healthcare (GPDPD.org).

In alternative development projects, small-scale farmers are trained in the cultivation of sustainable alternatives such as coffee or cocoa that are adapted to local conditions, and farmers are supported in the commercialisation of their products. Legal alternatives also include ecotourism and improving the framework conditions for rural development. This includes lowering the barriers-to-entry and expanding access to markets for legal products, promoting access to land titles and rural infrastructure and improving public services.

In partnership with BMZ and in collaboration with the Colombian Ministry of Environment, UNODC and other partners have implemented alternative development projects in three coca cultivating regions in Colombia (GPDPD.org). Working together to protect designated areas, plant new timber and fruit trees, which will create a source of sustainable income in the future, small-scale farmers are already generating income from the sustainable use of local fruits such as açaí or cocoa (GPDPD.org).

Carbon credits are a new concept in alternative livelihoods. The idea is for companies to offset their greenhouse gas emissions by buying and trading carbon credits. Companies are allotted a specific number of units of greenhouse emissions. Once a company exceeds its annual carbon budget, it needs carbon offsets to reduce its volume of emissions. If the company will exceed its allotment of emissions, it can ask another company to emit less so that the total amount of carbon in the atmosphere is still offset or reduced. Carbon credits derive from reduced emissions, removed emissions (e.g. carbon capture and planting forests) or avoided emissions (e.g. refraining from cutting down rain forests). “Carbon trading” and “carbon credits” have been the subject of much critique, not only by climate activists but by some scholars who regard it as a way for corporations to keep to ‘business as usual’ while providing a ‘green’ way to carry on emitting greenhouse gases.

Beyond corporations, the carbon trade exchange can also happen between countries. The UN-backed initiative “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation, plus the sustainable management of forests, and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks” (REDD+) is a framework through which countries can pay other countries not to cut down their forests through direct payments or carbon credits (Bertazzo 2019).

The usefulness of REDD+ as a conservation tool is not universally agreed. Some scholars regard REDD+ as a continuation of colonial conservation practices involving alienation of land, the restructuring of rules and authority in the access, use and management of resources (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones 2012). Others (Cavanagh, Vedeld, and Trædal 2015) point to ‘leakage’ effects on adjacent jurisdictions and deleterious effects on forest-dependent communities. In some cases, the territorialization of individual REDD+ projects and other voluntary carbon offset forestry schemes have resulted in the expansion of forest reserves and eviction of IPLCs across East Africa (Cavanagh, Vedeld, and Trædal 2015: 79). In some instances, illegal and informal trade exchanges in forest products are conflated (e.g. with the charcoal trade, which is different from the trade in timber). State actors are provided with incentives that threaten to further marginalize forest-dwelling communities instead of including and uplifting them (Cavanagh, Vedeld, and Trædal 2015). Meanwhile, conservation actors have often portrayed REDD+ as an opportunity to fund forest conservation around the globe. For example, the Nature Conservancy is supporting a REDD+ project in the Yaeda Valley, Tanzania, which is a home to Hadza hunter-gatherers. In 2019, the project earned USD 95,000 for the Hadza communities, which was used to ensure that the forests are protected and to improve communities’ lives through training game scouts, job creation and improving healthcare (Phakathi 2020).

REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation, plus the sustainable management of forests, and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks) is an effort to mitigate climate change. More specifically, REDD+ is an initiative seeking to design procedures to ‘compensate developing countries for reducing forest-related carbon emissions’ (Barr and Sayer 2012: 9). There are some features of REDD+ implementation that are problematic, such as property rights and resource control are, and have generated some debate thus far (Asiyanbi 2016: 146). There are many case studies highlighting these issues from multiple countries, including Brazil, Bolivia, Uganda, Nigeria and elsewhere (Lang, n.d.).

For instance, in Nigeria REDD+ is applied as a ‘total forest management strategy’ on a state level (Asiyanbi 2016: 147). In preparation of its implementation, a pilot state, Cross River State, stopped timber-based revenue targets, banned logging and created a militarized anti-deforestation Task Force to enforce this ban (Asiyanbi 2016). This can be seen as part of protectionist approach, called by Leach and Scoones (2015) as ‘fortress carbon.’ Asiyanbi (2016: 147) uses the term carbonised exclusion in his study to describe the implementation of carbon forestry policies in Nigeria that justify a political economy that is constituted around “a militarized protectionism that curtails local access to resources while perpetuating elite capital accumulation and forest decline.” It is also important to note that restrictions do not only apply to timber forest products but also to non-timber forest products. Although REDD+ does not seek to account for carbon in non-timber forest products, the logistics behind a total ban on logging has meant that in Cross River, the anti-deforestation task force has extended the ban to include a range of non-timber products such as rattan, chewing stick and firewood (Asiyanbi 2016). This has a knock-on effect on local communities’ livelihoods and businesses in these products.

Payments for ecosystems services (PES) is an incentive-based mechanism that offers benefits to farmers or landowners in exchange for managing their land to provide some sort of ecological service. These may include watershed protection and forest conservation, carbon sequestration and landscape integrity. Recipients of PES are rewarded with subsidies or market payments in an attempt to mimic market processes so that participation is beneficial for buyers and suppliers alike (Scheufele, Bennett and Kyophilavong 2018).

In developing countries, PES is often used as integral part of the support to the enforcement of the preexisting system of protected areas. In this context, the application of PES generally involves a restriction of traditional forest and wildlife use. The possible consequences of such changes, particularly with regards to conservation, have been poorly documented (Chervier, Le Velly, and Ezzine-de-Blas 2017). Countries such as Costa Rica, Mexico and China have started large-scale projects that provide payments to landowners for carrying out specific land use practices that have the potential to increase biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration and prevent erosion (Jack, Kousky and Sims 2008). In Europe, studies have been carried out on establishing PES schemes for enhanced biodiversity conservation. For instance, the Lonjsko Polje area in Croatia has been earmarked for a PES scheme in order to avoid abandonment of the land and maintain biodiversity (Kazakova et al. 2007). As a conservation strategy, PES emphasizes delivering socio-economic outcomes such as reducing inequality and marginalization of IPLCs; however, the achievement of those outcomes varies (Gaworecki and Burivalova 2017).

The Nakau Programme is the Pacific region’s first ‘Payment for Ecosystem Services’. The Nakau Programme is part of the REDD+ scheme (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation), a mechanism created under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Nakau Programme, which took five years to develop, meets international standards set by the Vivo Foundation (a standard that supports communities and smallholders in addressing climate change) and received funding from the European Union and the Asian Development Bank. It aims to give indigenous communities money for protecting forests as they would receive for cutting them down, with the ultimate goal of transforming the economic incentives that drive deforestation.

A notable example of payments for conservation is the landowning communities in the Drawa (Fiji) rainforests, located in the Wailevu-Deketi highlands. The Drawa Forest Conservation Project is an improved forest management project established with the primary goal to transition from commercial logging to a protected forest. This project accords protection to 4,120ha of tropical rainforest on the island of Vanua Levu and offsets 18,800 tons of carbon annually. The Drawa rainforests have a high endemism and provide habitat to endangered species such as Fiji ground frog (Platymantis vitiana). In 2018 Drawa became the first community in Fiji to receive carbon payments through the voluntary carbon market

Most forests in Fiji are on native land owned by communities with tenure rights that are held largely with clans. Although there are examples in Fiji of local communities setting up conservation areas to protect their forest resources, many are under pressure to issue leases to logging or mining companies for much-needed income. With inadequate legislation and government resources to secure the long-term protection of natural forests, conservation practitioners are looking at alternative models for establishing forest conservation areas in Fiji. One such model is the application of a forest payment for ecosystem services (PES) scheme to deliver both ecological and socioeconomic outcomes for local communities. PES schemes have been applied in Melanesia (e.g. Fiji, Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea) for forest ecosystems, but are poorly documented.

A study authored by Sangeeta Mangubhai and Ruci Lumelume entitled ‘Achieving forest conservation in Fiji through payment for ecosystem services schemes’ provides a case study from KIlaka village in Fiji. Here, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) has worked with traditional landowners to secure a 99-year conservation lease for 402 ha of pristine native forest in Vanua Levu. The lease, which was brokered through the government iTaukei Land Trust Board, provides an alternative source of income to logging and mining. The management plan which is nested within a larger ecosystem-based management plan for the district, sets out the co-management arrangements between the community and WCS, with the day-to-day management of the forest, enforcement, monitoring, and evaluation led by the traditional landowning clan. This PES model and co-management arrangement has potential for replication to other priority forest areas to meet Fiji’s obligations under the Convention on Biological Diversity, but at an estimated financial cost ranging from USD 69.0–287.8 million. (Mangubhai and Lumelume, 2019)

Fiji also recently became the first small island developing state to sign a landmark Emission Reductions Payment Agreement (ERPA) with the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) for up to USD 12.5 million in results-based payments. These payments will be awarded for enhancing carbon sequestration and reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. This presents an opportunity to incentivise indigenous communities to further forest (and hence biodiversity) conservation.

A study by Annabelle J Bladon et al published in 2016 suggests the application of payment for ecosystem services (PES) to tuna fisheries would be ideal in terms of their lucrative markets, but also particularly challenging in terms of the highly migratory nature of tuna. The Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) form a subregional alliance between eight adjacent Pacific Island states for the management of a purse seine skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) fishery. Although the institutional and political complexities of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) tuna fisheries might preclude them from suitability for PES on first assessment, the PNA has created an environment in which PES could be feasible. For this, Bladon et al provide the following background and justifications:

Demand for one or more ecosystem service where supply is threatened: Tuna has high economic value, and demand is therefore great from consumers, international retailers, producers and the economies of dependent Pacific States. PNA skipjack is considered to be sustainably managed, and the free-school skipjack fishery has gained certification by the Marine Stewardship Council scheme. However, those fleets that still target skipjack near fish aggregating devices catch undersize tuna and contribute to the overfishing of other species such as bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus). A PES targeting skipjack production and/or by-catch reduction might generate additional benefits over those delivered by current PNA management. Payments to PNA skipjack fleets channelled from various potential sources, including longline fleets that target bigeye, could incentivize free-school purse seining.

Availability of suitable baseline data and robust science: Good stock assessments and data on skipjack and bigeye movements are available, and relatively advanced spatial ecosystem and population dynamics models can also be used for the investigation of tuna management scenarios and interspecies interactions in the Pacific.

Clarity and security of property rights: WCPO tuna fisheries fall under the jurisdictions of multiple states that hold property rights within their exclusive economic zones (EEZs), and fishing operations range from coastal artisanal fleets to industrial purse seine and longline fleets on the high seas. The variable movements of tuna therefore complicate the identification of buyers and providers and may create a free-rider problem; one buyer might end up paying for conservation measures while a distant actor reaps the benefits. However, the PNA states have asserted their property rights to control 70% of WCPO and 50% of global skipjack tuna catch and established high-seas closures in the areas between their EEZs. The PNA also operates a vessel day scheme for purse seiners, a rights-based transferable effort scheme where PNA members are allocated fishing days which they can trade between themselves and allocate to distant water fleets at their discretion. The strengthening of rights that this entails would make it possible to clearly identify providers in a PES regime.

Capacity for hybrid multi-level governance: PNA was established following mutual concerns of the participating states over sustainability and economic opportunity, and there has since been a paradigm shift in the way they view and manage their resources. In addition to political will from individual states, the PNA forms an institutional basis for the implementation of a PES scheme, although the complexity of creating such a large-scale and international PES should not be underestimated. PNA resources are not constrained solely within the PNA states and fall under the jurisdictions of multiple overlapping regional management and advisory bodies, including the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), PNA and TVM (Te Vaka Moana). A multi-level governance framework for the integration of each of these bodies would be desirable, but mutual economic and ecological objectives would first need to be identified.

Capacity for MCS: PNA terms of licence enforce strict management rules with 100% observer coverage, and the vessel day scheme provides a mandatory real-time vessel monitoring system, which might allow payments to be conditional on actions or outcomes. Enforcement is difficult on the high seas, but PNA has also established high-seas closures in areas between EEZs, reducing IUU and therefore the risk of free-riding.

Potential for financial sustainability: PNA management is currently funded through fixed conservation levies from fishing vessels, and although these levies are not currently conditional on meeting any specific ecosystem objectives or MSC standards, this could provide the basis for a sustainable PES. Furthermore, there is already strong supply chain and market interest in the sustainability of the fishery; through the market access enabled by its joint venture with import and branding agency Pacifical, the PNA generates a 20% premium on free-school skipjack products via MSC certification and labelling, the majority of which is channelled back to industry. Its co-branding programme with Pacifical also allows traceability of a can of tuna back to the vessels and factory involved in its production – a system that has created an unprecedented level of transparency within the supply chain and that could allow corporate responsibility to be apportioned accordingly.

Verdict: This case-study fully satisfies five of six preconditions. The only theoretical barrier to PES is the complexity of WCPO tuna governance; increased levels of coordination between PNA and other governance bodies may not be a realistic expectation.

Non-wildlife based alternative livelihoods can also play an important role in biodiversity conservation. This entails incentivizing wildlife-friendly agriculture through better prices, market access or other benefits for producers. Small-scale farmers receive assistance or counsel on managing grazing livestock or fields in sustainable way, which is sometimes linked with certification and labeling (Roe et al. 2020).

Microcredit is a common form of microfinance that involves lending small amounts to individuals to help them become self-employed or grow a small business. These borrowers tend to be low-income individuals from less developed countries. Also known as “microlending” or “microloans,” most microcredit schemes rely on a group borrowing model first developed by Nobel Prize winner Muhammed Yunus and his Grameen Bank (Hayes 2020). Microcredits are regarded as important tools to reduce poverty and empower communities in different regions of the world (Ahmad and Rahman 2017). Ahmad and Rahman (2017) studied effects of micro credit programming on fuel wood conservation in Chitral Gol National Park region in Pakistan. In Pakistan, the forest cover is being reduced due to heavy reliance on using forest products as fuel. Consumption is higher in rural areas where there are no cheap fuel alternatives. The micro credit programme was provided for local communities to adopt alternative livelihoods or purchase alternative fuels. This led to the reduction of the quantity of fuel wood collected. In Ahmad and Rahman’s study, microcredit recipients consumed significantly less fuel wood than those who did not. Still, Ahmad and Rahman identified a marked gender bias as very few women benefited from the microcredit programme, and loans were given to those already employed rather than those who were looking for a capital to start up a business (Ahmad and Rahman 2017).

Another micro-credit initiative is Community Conservation Banks (COCOBA). Initiated in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania in 2009 by the Frankfurt Zoological Society, COCOBA aims to address the economic causes of poaching as well as improve livelihoods of communities in the surrounding areas of the park (Kaaya and Chapman 2017). The overarching aim of COCOBA is “to strengthen conservation through sustainable poverty reduction efforts” (Sulle 2012: 13). This is done through the provision of low-interest loans that individuals can use to establish environmentally friendly businesses. Although community conservation banking, like other microcredit institutions, aims to reduce poverty, it differs from others as it includes environmental conservation as part of its objectives; for example, poachers must stop all types of poaching if they wish to join the conservation banking programme (Kaaya and Chapman 2017). Kaaya and Chapman interviewed people from villages bordering Serengeti National Park about the impacts of COCOBA and the role it plays in local livelihoods. The majority (90 percent) of the respondents participating in income-generating actions pointed out that COCOBA had helped to improve local people’s livelihoods and with that, there were reduced incentives for poaching (Kaaya and Chapman 2017). Almost all participating former poachers stated that it was ‘more beneficial’ to participate in COCOBA supported activities such as animal husbandry and vegetable farming than in bushmeat poaching, as it is also “more sustainable and safer” (Kaaya and Chapman 2017: 469). Like other initiatives, the microcredit approach is not without its discontents (see class exercise).

Acknowledging the challenging financial situations of many women, especially in rural communities such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, Lewa Wildlife Conservancy launched a Women’s Micro-Enterprise (WME) programme in 2001, and the first credits were rolled out in 2003. By using microcredits, women are able to start up their own small businesses in agriculture and other sectors and contribute further to their and their families’ livelihoods. Some 1,800 women have benefited from the micro-enterprise programme; in 2017, 11 million Kenyan Shillings were disbursed to women with a repayment rate of 90 percent being maintained through the programme.

More information on the project can be found here.

Community-based conservation has received a fair amount of criticism which can roughly be divided into critiques relating to governance and regulation deficits, problems with benefit distribution, unequal power relationships including elite capture and the marginalization or exclusion of women and youth from programming.

Corruption poses a significant risk not only to natural resource management but to conservation in general. The monetary values involved in natural resource exploitation are appealing for both corruptors and the corrupted alike. It is important to note that corruption is often rooted in existing inequalities, power relationships and bureaucratic structures (Dutta 2020b). Corruption places limitations on the genuine devolution of rights over wildlife to local people, and a common cause of failure of community projects relates to the unwillingness of powerful actors to let go of control and authority over natural resources (Cooney et al. 2018a). Corruption is not only an issue for community-based conservation but affects the broader wildlife trade including legal, illegal and informal trade exchanges. (More information on wildlife trafficking and corruption can be found in Williams et all 2016, as well as in Module 2 of the Wildlife Crime Series; see also University Module Series on Anti-Corruption).

Community-based wildlife reforms have been encouraged and supported by foreign donors and international conservation organizations (Nelson and Agrawal 2008). While these efforts are laudable and reflect the nature of the need for cooperation and support across the global commons, there is a need for careful management of financial support provided by donor agencies to avoid a culture of aid dependency. Donor support should be balanced against the ultimate objectives of any community conservation project and its long-term feasibility so that the support does not end prematurely before the initiative has become self-sustaining (Cooney et al. 2018: 35). IPLCs should be included in discussions of how to prevent illegal wildlife trade so that responses to these crimes are appropriate in the local context and do not encourage “a culture of passive reliance on an externally provided financial benefit” (Cooney et al. 2018: 40).

Building on donor reliance, some donor funded projects may focus on the outputs of community conservation projects rather than on the needs of local and national stakeholders. By doing so, “the ownership of community conservation has tended to remain external to national conservation agencies” (Barrow, Gichohi and Inflied 2000: 139). Some conservation initiatives are perceived as ‘donor projects’ that were conceived in boardrooms of conservation NGOs and donors in northern or urban centers far away from the places where the projects are implemented (Barrow, Gichohi and Inflied 2000). Additionally, there is concern that if national conservation agencies fail to take a leading role in community conservation projects, such projects may not be supported by IPLCs or ‘labelled as ‘donor driven’ programmes’ (Barrow, Gichohi and Inflied 2000: 140), which can limit their sustainability or desirability by the very populations they aim to help.

Women and girls are frequently left out of interventions and assessments of their role in wildlife trafficking supply chains and responses (Agu and Gore 2020). This does not augur well for any community conservation and trafficking interventions and contradicts the tenets of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Achieving equity in patriarchal societies is not an easy feat. For instance, a study undertaken by Baynes and co-authors (2019) on forest and livelihood restoration projects in Papua New Guinea and the Philippines shows that women are traditionally excluded from the land management decisions. Additionally, the level of marginalization can differ between women. Nightingale’s (2002) research on community forestry in Nepal found that caste is an important variable that can limit women’s participation in user-group committee meetings. (Nightingale 2002).