The Small Arms Survey Trade Update 2017 uses as its base United Nations Comtrade data from the years up to 2014. As the update clarifies, States voluntarily supply data to Comtrade, and thus " While UN Comtrade captures much international commercial activity, it does not capture all small arms transfers as many states do not report them to United Nations Comtrade, or do so only partially" (Holtom and Pavesi, 2017: 14). Other data used in this section comes from SIPRI, which has an international focus, as well as from the Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT), which has a United Kingdom/European Union focus.

The Small Arms Survey has produced a useful list of some of the largest companies producing SALW and a non-exhaustive list of their SALW products, and this has been incorporated into Table 3.2, along with the country in which the company is primarily located, which did not feature in the original list. Some of the companies (e.g. Anschütz and Heckler & Koch) focus primarily on firearms and firearms related accessories, while others (e.g. NORINCO and Saab) have sections of the company that focus on firearms but have considerable business in other fields. The table below sets out information about some of the companies engaged in this industry. The Small Arms Survey's study provides additional details.

|

Company |

Country |

Products |

|

Germany |

Hunting and sporting rifles | |

|

USA |

Pistols, submachine guns, assault rifles, grenade launchers and mortars, cartridge-based ammunition and rifle grenades | |

|

Italy |

Hunting and sporting rifles, defence pistols, shotguns and carbines | |

|

Czech Republic |

Hunting rifles, pistols, submachine guns and carbines | |

|

UK |

Pyrotechnics, medium and large calibre ammunition, 40mm grenades | |

|

Germany |

Recoilless shoulder-fired anti-armour weapons | |

|

Belgium |

Handguns, rifles, shotguns, machine guns, ammunition and less-lethal launchers | |

|

USA |

Small and medium calibre ammunition, mortars | |

|

Austria |

Handguns | |

|

Germany |

Handguns, rifles, submachine guns, machine guns, and grenade launchers | |

|

India |

Handguns, rifles, submachine guns, machine guns, mortars, medium calibre firearms and recoilless guns | |

|

Brazil |

Pistols, rifles, light weapon ammunition and mortar shells | |

|

Israel |

Pistols, submachine guns, carbines, rifles, and machine guns | |

|

Norway |

Small calibre ammunition, fuses and pyrotechnics, shoulder-launched anti-armour and bunker-defeat systems | |

|

France |

Medium calibre ammunition, pyrotechnics | |

|

China |

Pistols, assault rifles, small arms ammunition | |

|

Pakistan |

Infantry rifles and machine guns, small arms ammunition, mortar bombs and pyrotechnics | |

|

USA |

Shotguns, handguns, rifles, small arms ammunition | |

|

Sweden |

MANPADS, shoulder-fired anti-armour weapons | |

|

USA |

Handguns, shotguns, rifles | |

|

Singapore |

Assault rifles, machine guns, 40 mm grenade launchers and ammunition, small arms ammunition | |

|

Serbia |

Hunting and sporting rifles, assault rifles, machine guns and grenade launchers |

In addition to these major producers, there are countless smaller producers, distributed across the world.

The Small Arms Survey also outlines the major manufacturing States for firearms, saying that the "[m]ain producing countries include all the top exporters (USD 100 million or more in a single calendar year) as well as several countries with significant industrial capacities that meet the needs of the domestic market" (Jenzen-Jones, 2014: 3). The value of the domestic market has yet to be estimated.

The Small Arms Survey Trade Update 2017, published in 2018, gives a good indication of the major exporting states for SALW, and when combined with data from SIPRI gives a good overall picture of which States are the source of the majority of weapons.

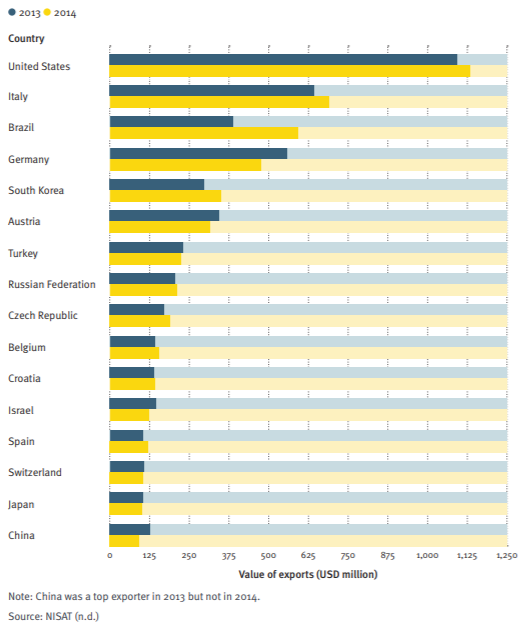

Earlier in the Module, Figure 3.2 showed that the top ten exporting states were responsible for almost all of the global exports of arms during the Cold War era. Although the players may have changed slightly since the Cold War, the SIPRI data for 2017 still shows that the top ten exporters continue to be responsible for 92 per cent of global arms exports (SIPRI, 2017). Holtom and Pavesi (2017) narrow the trade down from all arms to just small arms and light weapons, and their data is reproduced in Figure 3.4 below. The data they use is slightly older than that used by SIPRI but, nonetheless, show interestingly that the key exporting States change, and the dominance of the arms trade in general is not wholly reflected in the SALW trade.

The United States tops both the SIPRI list for total arms exports and Holtom and Pavesi's list for SALW exports in 2017. Russia, however, slips from second place in terms of total arms exports to eighth for SALW, while Brazil climbs from 24 th place in total arms exports to third for SALW in 2017. A further interesting point is the presence of Croatia on the SALW list, in eleventh place. It does not appear at all on the SIPRI list, but neighbouring Serbia, Hungary, and Bosnia-Herzegovina do all appear (in 37 th, 44 th and 45 th places respectively). Module 8 (Firearms, Terrorism and Organized Crime) gives examples of weapons exported from this region which were used by criminal groups.

After the presentation of the main sources of the world's firearms, it is imperative to consider the destination of those weapons. This section of the Module will not focus on the illicit movement of weapons, but will look instead at their stated intended, legal destination.

One way for the exporting State to try and ensure that the transfer of firearms is legitimate is through End-Use Certificates (EUCs). The EUC is a document supplied to the exporting country from an institution of the importing country, which describes who is the recipient of the goods and sometimes can identify for what purpose they will be used. However, any certification scheme is potentially open to misuse and there are various examples where the lack of stringent pre- and post-licence controls has resulted in diversion of firearms into the illicit market (Greene and Kirkham, 2007). It is clear, therefore, that when exercising their export controls, States should not simply rely on EUCs but establish a comprehensive system of post-licence and post-shipment verification.

Greene and Kirkham (2007: 5) suggest a series of minimum standards, which they argue all States should put in place to stop the diversion of legitimate weapons to illegitimate users. Their proposals include:

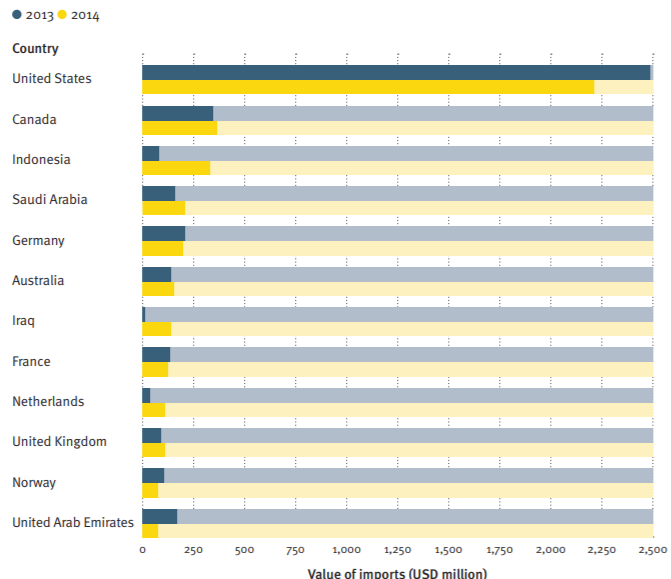

Holtom and Pavesi list the top twelve importers of only SALW for 2014 reproduced below as Figure 3.5. Again, the difference between this list and the SIPRI list for all arms imports is stark. The United States and Canada, which top the SALW import list, move down to 16 th and 21 st place respectively in relation to arms in general. By contrast, of the top twelve states for overall arms imports, only four appear on the top list of SALW importers (Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Australia and the United Arab Emirates).

The United States is clearly the largest importer of SALW by a considerable margin (roughly seven times greater value than Canada), and this is unsurprising when two separate estimates are combined. In his research, Karp (2007: 39) establishes that the civilian ownership worldwide is approximately 650 million, which represents 75 per cent of the known total, and his additional research published in the Small Arms Survey reveals that circa 270 million of these firearms are in the in the United States (Karp, 2011). Module 6 (National Regulations on Firearms) and Module 7 (Firearms, Terrorism and International Organized Crime) deal with the perceived need for civilian gun ownership (which includes individuals, criminals and organisations).

Given the focus of concern on export controls, and of the potential misuse of EUCs, it is worth considering briefly the issue of corruption in States with large SALW imports. For more information on the impact of corruption, please refer to the Module Series on Anti-Corruption.

The Small Arms Survey has a Transparency Barometer, which attempts to provide an assessment of how much information is shared publicly by major exporters. Comparing this list to Holtom and Pavesi, Saudi Arabia and Israel, for example, score respectively 0.5 and 0.75 out of twenty-five (and are thus not at all transparent), while Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have the highest transparency scores (20.25, 19.5 and 19.25 out of 25). The United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) emphasizes that transparency in armaments is a key confidence-building measure, which may encourage restraint in the transfer or production of arms and can contribute to preventative diplomacy. While the comparison of importing states and transparency is no more than one indicator of potential for misuse, it is interesting to see the correlation, and makes clear the need for a regulatory framework for the legitimate arms trade.

One of the important aspects in making sure that legitimately produced firearms and SALW remain in the hands of those who are entitled to possess them is knowledge of who is in control of a weapon at any time. As long ago as 1969, albeit in a national rather than international context, it was suggested that " the danger of transfer of firearms from legitimate to illegitimate users might be somewhat abated by a registration or transfer notice system" (Newton and Zimring, 1968: 127).

A well-regulated international arms trade has the potential to reduce the quantity of firearms that are diverted into illicit hands, and thus to assist in the efforts to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 16 "Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) lists small arms and light weapons as areas of concern under Rule of law, justice, security and human rights, and also covers conflict prevention as another area in which it can assist States. At the international level, the 1924 Covenant of the League of Nations was already concerned with reducing levels of State arsenals. Its Article 8 includes two parts, which are of immediate relevance to this Module:

Paragraph 1: "The Members of the League recognise that the maintenance of peace requires the reduction of national armaments to the lowest point consistent with national safety and the enforcement by common action of international obligations" and

Paragraph 4: "The Members of the League agree that the manufacture by private enterprise of munitions and implements of war is open to grave objections…"

Paragraph 1 has clear links to the discussions in Section 2 about the balance that States seek to strike between security and the ability to carry out their obligations. There is also a link between Paragraph 4 and the discussion in Section 1 about the private manufacture of weapons during the First World War. In the United Kingdom, the Royal Commission on the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Arms reported in 1936 on the practicability and desirability " of a prohibition of private manufacture of and trade in arms and munitions of war, and the institution of a State monopoly of such manufacture and trade" (National Archives, 1936).

The United Nations replaced the League of Nations, but Articles 1(1) and 2(3) of the Charter of the United Nations reflect Article 8:

"To take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace" (Article 1(1)), and

"All Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered" (Article 2(3)).

After the end of the Second World War, the international community formed several inter-governmental organizations in addition to the United Nations, designed to bring order to the international economic system. The so-called Bretton Woods agreements resulted in the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), now known as the World Bank. A need arose for an organization, which could streamline international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers, e.g. quotas and tariffs. The first stage of this was the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947, and lasted for close to 50 years until the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1993.

Article XXI of GATT, Security Exceptions, stated that: "Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed

There was some clarification as to what amounted to a State's " essential security interests", triggered by an unsuccessful complaint by Czechoslovakia in 1949. The discussion around that complaint clarified that "every country must be the judge in the last resort on questions relating to its own security. On the other hand, the contracting parties should be cautious not to take any step which might have the effect of undermining the General Agreement" (Summary Record of the Twenty-Second Session, 1949: 3). When the WTO replaced GATT, Annex 1A of the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization incorporated the 1994 text.

The provisions of Article XXI mean that States can make a judgement call about what they disclose in terms of their arms deals with other States, which allows considerable scope for secrecy in arms deals. SIPRI, CAAT, the Small Arms Survey, and other organizations maintain registers of international arms transfers, but they all rely on public domain data, which means there are inevitable transfers unrecorded.

In addition to general trade agreements, there were some specific limitations placed on the arms trade, albeit with limited geographical scope. The Coordinating Committee on Export Controls (CoCOM) was set up in the aftermath of the Second World War by the Allies as a way of stopping the arms trade with countries in the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) bloc (originally the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Romania, and later Cuba, East Germany, Mongolia and Vietnam). As Lipson (1993: 33) points out, " it did not last long after the end of the Cold War" and was phased out in 1993, being replaced in 1996 with the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual Use Goods and Technologies.

The Wassenaar Arrangement is described as " the first post-Cold War export control regime" (Lipson, 1999: 33) but its reach has always been limited by its admission criteria in Appendix 4:

When deciding on the eligibility of a state for participation, the following factors, inter alia, will be taken into consideration as an index of its ability to contribute to the purposes of the new Arrangement:

Small arms, light weapons and MANPADS are included in Appendix 3 and all are broadly categorized rather than tightly defined. Unlike CoCOM, which was focused on restricting arms transfers to the Soviet Union and its allies, Kimball (2017: 1) points out that the Wassenaar Arrangement is " not targeted at any region or group of states, but rather at "states of concern" to members. Wassenaar members also lack veto authority over other member's proposed exports, a power that COCOM members exercised."

Section 1 of the Initial Elements of the Wassenaar Arrangement shows that the purpose of the group was " to contribute to regional and international security and stability, by promoting transparency and greater responsibility in transfers of conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies, thus preventing destabilising accumulations." The links between this purpose and SDG 16, as discussed earlier in this Module, are evident. All these measures are supra-national, but none has global application. Wollcott (2014: 1) identifies the 1991 United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) as being " the key international mechanism to promote predictability and transparency in the conventional arms trade."

In 2001, the United Nations Conference on the Illicit Traffic in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects led to the adoption of the Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat, and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons, in All Its Aspects. Generally referred to as the PoA, this had the advantage over the UNROCA insofar as it specifically focused on SALW, and is a crucial element of international regulation, but is only indicative of State intentions and not binding.

Woolcott (2014: 2) argued that many States became concerned that "…. the international trade in bananas was more tightly regulated under international law than conventional arms." Thus, in December 2006, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 61/89 asking the Secretary General to seek the views of Member States on the feasibility, scope and draft parameters for a comprehensive, legally binding instrument establishing common international standards for the import, export and transfer of conventional arms. Module 5 (International Legal Frameworks) deals with the specific details of the Arms Trade Treaty in more depth, and Module 6 (National Regulations on Firearms) covers some examples of national implementation of the provisions of the Treaty, but Woolcott (2014: 3-5) provides a useful two-page step-by-step run through the stages in the development of the ATT.