It is useful to approach the issue from both the supply and demand sides and the roles played by criminal actors on both sides of this equation.

In the firearms context, there are debates over who is the dominant trigger factor: supply or demand. Sometimes supply factors seem more important; at other times and places demand factors dominate. In the situation of high demand and low supply, the suppliers tend to dictate the market, while in the absence of demand and stock supplies, the demand dictates the market unless the suppliers take actions to increase the demand, for example by fueling dormant conflicts. Arms control scholars have tended to work from the supply side, focusing upon the production and distribution of weapons and the ways and means they slip from legal to illegal. Schroeder et al. (2006) linked the illicit supply of firearms to shady international weapons dealers and brokers or ' rogue states'. Further research has shown, however, that patterns of illegal firearm supply reflect very closely the patterns of supply for legal small arms as well as representing enduring post-conflict legacies (Bourne, 2007).

While a good deal of research has emphasized the rational motivations of people involved in illegal firearm supply (money; power; political affinity; influence), Arsovska and Zabyelina (2014: 401) draw attention to a range of cultural and social factors shaping both supply and demand. These, they suggest, include: " patriotism (a system of values, in which love for, or devotion to, one's country and civic virtue glorifies arms possession); conflict mentality (a feeling of fear, insecurity, distrust that people often gain in the aftermath of durable conflicts and prolonged socio-economic distress); and gun culture (illustrating pride in and passion about possession and/or use of arms)".

Among the factors that can contribute to the demand for illegal firearms, the following ones appear to be more prominent (Saferworld, 2012):

In addition, gang cultures, civil conflict, racial and ethnic tensions, wider cultural endorsements (for example the glamorizing of firearms in popular culture), terrorist radicalization, and loopholes and anomalies in firearms control regimes can all accelerate demand. In turn, demand can incentivize supply.

The supply of illegal firearms differs in terms of scale and modalities - countries with a high degree of control encounter predominantly small and irregular supplies. On the other hand, countries with looser control regimes or less effective enforcement measures, such as conflict cultures and conflict states, are more likely to experience large container shipments arriving by land, sea or air (Griffiths and Wilkinson, 2007: 20-25).

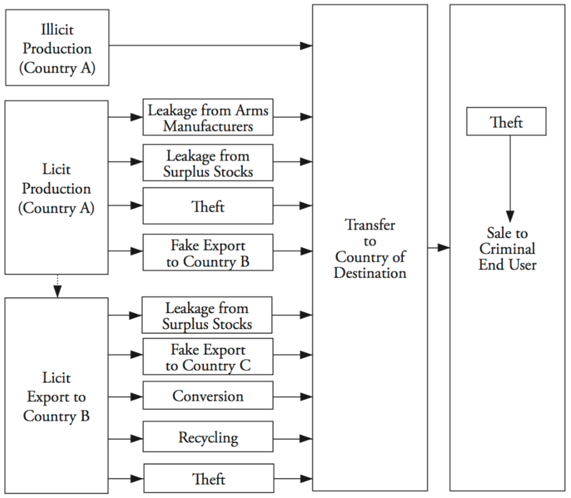

Module 1 (Introduction to Availability, Trafficking and Criminal Use of Firearms) shows how firearms are durable, long-lasting items. Virtually all firearms start life in legal production, but the steps in the life cycle of a firearm, from production to final end-use are complex and diverse, multiplying the risk that the weapons enter the illicit market. It is important, therefore, is to assess the points at which and ways that legal firearms slip into illegality. The following diagram provides an outline of where criminals and terrorists can obtain firearms illicitly:

While this diagram portrays the journeys that firearms might take from the licit to illicit market, it does so in a general sense. In real contexts, and depending upon the kinds of regulatory regimes in existence, those journeys might take very different forms while also representing some markedly different scales of illegal activity, ranging from large-scale trafficking to small-scale smuggling activities (so-called ' ant-trade'). In addition, the use of new technologies, such as 3D printing and the various forms of electronic means of communication (Facebook, Viber, Skype, internet forum boards, darknet), play an increasing role in this type of emerging small-scale illicit trade.

The cases below illustrate through the story of an illicit broker on the one hand, and the journey of a weapon on the other, the variety of typologies and contexts involving illicit arms trafficking. Discussed later in the Module will be further details on large and small-scale illegal production, trafficking and delivery.

The following case study is largely based upon the report "Guns, Planes and Ships: Identification and Disruption of Clandestine Arms Transfers", by Griffiths and Wilkinson (2007). The clandestine broker at the centre of major weapons trafficking operations to Iraq, Liberia, Sudan, Burma, Libya and Somalia was Tomislav Damnjanovic, who gained his first experience in chartering and organizing sanctions busting flights into the former Republic of Yugoslavia as that country began to fall apart, becoming 'a smugglers paradise' in the 1990s. He chartered planes 'throughout Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe, supplying everything from humanitarian aid to hand grenades'. Damnjanovic learned to operate through a network of shell companies and sub-contractors and later began to link with the Italian mafia and organized criminal groups in Switzerland smuggling drugs and contraband cigarettes into Europe. Later, in 2004, having become manager of a Serbia based, but Russian owned, air freight company he began to diversify into arms trafficking, recognizing that he would be well-positioned to exploit the developing transport market, comprising both legal and illegal shipments, shifting the region's massive stocks of surplus AK-47s and ammunition that US, Israeli, Arab and German arms brokers had begun buying up to supply the new security forces in Iraq under Pentagon contracts. And even when weapon supply eventually reached saturation points in the conflict destinations, there remained still a continuing demand for ammunition. Damnjanovic organized dozens of Ilyushin cargo aircraft flights into and out of North Africa, exploiting the cover provided by his legitimate contract credentials, financial and security connections, carrying everything from expensive consumer goods and smuggled cigarettes to Kalashnikovs and missile launchers, often shipped under the guise of humanitarian aid. On one of these occasions, whilst flying legitimate cargoes of arms into Iraq, one of Damnjanovic's planes diverted to Oman to collect an unspecified cargo. The following day the same plane was observed by United Nations personnel at Mogadishu airport in Somalia where UN investigators reported that the plane was delivering a cargo of arms and ammunition to Islamic militia groups. Damnjanovic insisted that the plane landed to refuel but the Omani authorities disputed this claim. Suspicion had first fallen upon Damnjanovic's air freight business after one of his Ilyushin planes was intercepted in Spain with an illegal cargo of millions of contraband cigarettes destined for the European Union. Documents seized when the plane was raided pointed to other aspects of Damnjanovic's illegal trafficking operations.

According to Griffiths and Wilkinson (2007: ii), the case illustrates many features of illicit firearm trading. The first is that " arms smuggling pays... if the smuggler is smart and careful and if he mixes legal arms deals with illegal ones". According to these authors, " arms smuggling pays better than narcotics over the long term because traffickers are less likely to get caught and their logistics networks can also transport legitimate goods at the same time. Drugs are more lucrative than guns in terms of shipment density versus value, but whilst dealing in heroin or cocaine is always against the law, this is not the case with small arms". There is, they argue, " no grand conspiracy, just persistent systems failure, lack of visibility or accountability and oversight". The identification, disruption or seizure of illegal arms supplies are continuously frustrated by the failings of the international aircraft regulation system, ineffective rule of law, corruption, lack of political will and poor coordination between agencies. These are the most common loopholes and opportunities exploited by the illicit arms traffickers.

Work in the United Kingdom has identified a number of diverse sources of illegal firearms, including:

To illustrate the progression of a particular firearm type from the licit to illicit markets within a series of relatively highly regulated European firearm regimes, De Vries (2011) undertook what she described as a ' script' analysis of the forward journey of a number of legally manufactured blank firing and alarm guns into criminal hands .

The journey - or script - in question comprised a series of logistical steps or 'scenes' in which a variety of actors performed particular roles. The actors in question could include: arms manufacturers, arms dealers, initial criminal purchasers, transporters, converters, 'bulk' purchasers of the converted weapons, couriers and retail sellers and end purchasers and criminal users. In this particular case, a significant connection between the actors in the central part of the supply chain was a common minority ethnic background. The guns were initially sourced from Italian and Turkish manufacturers, transferred and converted to live firing in Portugal and sold to criminals and gangsters in the Netherlands, some eventually reaching the United Kingdom. Most of the weapons that were found in the Netherlands had been converted in small-scale conversion locations in Portugal. Investigations by the Dutch police led to the identification of several groups of migrants that were situated in the Netherlands and that are were involved in different scenes of the crime script of converted firearms. Their transnational relationships facilitated their criminal activities. The fact that the weapons that were converted in Portugal show up on the Dutch criminal market was explained, in part, by the transnational relationships that exist between Cape Verdeans living in Portugal and the Cape Verdean community in the Netherlands. Cape Verdean criminals have played an important role in this case of the smuggling of converted firearms into the Netherlands. (De Vries, 2011)

Three-dimensional printed arms are an emerging source for illicit firearms supply. By 2013, the availability of 3D printing opened up a further opportunity for illicit firearm manufacture. At present, this option appears rather less practicable and scarcely economically viable as regards the production of a fully functioning firearm, but the advent of composite and inter-changeable firearm systems makes it more likely that firearm components might be 3D printed and circulated (Jenzen-Jones, 2015; Daly and Mann, 2018). Although the technology is still in its early stages, 3D printed firearms that are operational have been made and fired. Several questions remain in terms of the legality and regulations required to govern the production of this new type of firearm. Australia has introduced the first legislation on this subject in 2015 with the changes in section 51F of the 1966 Firearms Act, which foresees criminalization of the possession of a digital blueprint for the manufacture of a firearm on a 3D printer. The digital blueprint is defined as any type of digital reproduction of a technical drawing of the design of the firearm. The most progressive step is made through the definition of "possession of a digital blueprint", which foresees two hypotheses. First is the possession of a computer or data storage device, and holding or containing the blueprint or document in which the blueprint is recorded. Second is the control of the blueprint held in a computer in the possession of another person, regardless of the computer being in or outside Australian jurisdiction.

Methods of trafficking firearms are in continuous evolution and adapt very fast to law enforcement response, taking advantage among others of the new technologies including the Internet and other electronic means of communication. The use of the Internet, for example, has opened a new dimension in matching demand and supply. Moreover, its hidden side, also known as " Dark Web or darknet", opened opportunities for criminals to engage in illegal online trade of firearms and adopt crime as a service (CaaS) model as a key distribution channel (Europol, 2014). See also the UNODC Teaching Module Series on Cybercrime for additional information.

Crime-as-a-service model stands for the development of advanced tools by criminals, which are then offered up for sale. In the case of firearms, this entails the provision of guidelines on manufacturing of firearms through assembly of parts or through distribution of blueprints for printing 3D firearms. It also includes instructions on how to convert signal or gas pistols, as well as offering functioning firearms, components and ammunition. This model has a powerful effect on firearms trafficking because it lowers the bar for inexperienced actors to gain access to information on manufacturing firearms and illicit firearms. This is important in determining the profile of the suspects since this distribution channel allows easier access to illicit firearms for persons with no criminal past as well as persons engaged in poly-criminality. The online trade takes place at specific marketplaces where there is a regional focus with the emergence of language specific platforms.

The illegal trade of firearms has also used the darknet. Initial discussions on the methods for purchasing and selling firearms, parts, components, and ammunition, along with the size, scope and value of the illegal trade, the main shipping routes and most common shipping techniques, as well as the implication of this activity for law enforcement agencies have been subjects of intensive debate (Paoli et al., 2017; Paoli, 2018). Compared to other forms of firearms trafficking, the scale of trafficking through the darknet, in volume and value, is rather limited (Paoli, 2018). This illegal trade presents a challenge and has impact on firearms trafficking linked more to the broader criminal context where individuals illegally obtain small number of firearms. Due to the requirements for specific infrastructure and services, which provide the background for this type of trade, it will not have impact on firearms trafficking in the context of armed conflicts (Paoli, 2018). Nevertheless, this threat needs addressing at a political level and respective organizational, capacity building and technical measures need to be undertaken. This includes building this type of trafficking into national strategies, designating law enforcement units for its monitoring, and equipping them with relevant knowledge and equipment.

Criminals also use less sophisticated means for illicit trade online that do not necessitate venturing into various marketplaces in the " Dark Web". Facebook profiles, or Internet forums, can offer illicit firearms, and merchandise be delivered to buyers through postal services. In 2018, the Security Service of Ukraine finalized the investigation against an organized criminal group, which had specialized in procuring illegal firearms and their parts, and deactivated firearms, from the United States and the European Union. Delivery took place in parts through courier companies to Ukraine, with subsequent re-assembly or re-activation, and sales offered via specialized online forums (SBU, 2018). The operation resulted in the seizure of three machine guns, three automatic rifles, two rifles and thirty pistols. This case once again highlights the use of the darknet and other online venues mainly for negotiating the terms of the illegal trade, and sometimes for transfer of funds. However, the offence of illicit trafficking is committed through the unauthorized cross-border transfer of the firearms. All activities prior to the physical transfer across the State lines might be qualified, subject to the collected evidence, as an attempt to aid and abet firearms trafficking if domestic criminal law defines such actions as an offence. The detection and interdiction of firearms trafficked through online channels requires the monitoring of both online activities and postal deliveries.

There are some obvious differences between the actors in the legal and illicit markets for firearms. National and international laws govern the legal trade and its actors operate in compliance. Actors are identifiable and accountable for their actions and strive to maintain their reputation and integrity to ensure continuous expansion of their profits. They include:

At any of these points along the transfer chain, a firearm can exit the legal circuit and enter an illegal one, sometimes with the support of the legal actors.

Actors in the illicit market are driven by the same focus on profits while circumventing the existing control regimes. As Clegg and Crowley (22001: 2) argue, " Arms traders supplying illegitimate customers usually exploit loopholes or weaknesses in their national arms control systems and in those of third countries. Countries with weak export and import controls may be targeted, and vague definitions, poor licensing procedures, corruption, and a lack of capacity to enforce customs controls provide arms brokering and transportation agents with an opportunity to move arms along clandestine supply routes."

Licensed firearms dealers in various parts of the world also play a significant role in fostering illicit trafficking. The National Ballistics Intelligence Service reported a series of cases in the United Kingdom during early 2018, which involved registered firearms dealers converting and re-engineering obsolete and antique firearms and then manufacturing bespoke ammunition calibers for them. These were then sold on to criminal groups (NABIS, 2018).

One of the most prevalent methods of trafficking illicit weapons is to use a " straw purchaser"; that is someone eligible to purchase for someone who is not, a process in many countries against the law. It is, for example, a major cause of weapons trafficking from the United States with US residents with no criminal records relatively freely purchasing firearms legally, but them ending up in the hands of drug cartels in Mexico. Some 80% of illegal firearms recovered in Mexico and successfully submitted for tracing had originated from legal sales in the USA (Schroeder, 2013).

In some countries organized criminal groups (OCGs) engage in trafficking firearms among other illicit activities, including trafficking in human beings or drugs (for further information on the links, see the UNODC Teaching Modules Series on Organized Crime, particularly Modules 3 and 16). Arms trafficked for self-use increase their power and strength, or are used in exchange for other commodities, such as drugs. Arms trafficking may be a side product of other principal activities, taking advantage of the already existing channels and routes. Strazzari and Zampagni provide an excellent overview of the situation in Italy in this respect, describing the modus operandi of the organized criminal groups, their interactions with foreign criminal organizations and main use of illicit firearms (Duquet, 2018).

Transport companies, whether wittingly or unwittingly, are also major players in the illicit market, with supply by air to illicit end users and destinations often involving the violation of civil aviation rules (Small Arms Survey, 2010). This leads us now to consider the particular forms of illegal firearm delivery.

While small scale trafficking occurs through various concealment strategies, the options for delivering large scale transfers can be limited to relatively few choices. In addition to methods referred to already, the study by Griffiths and Wilkinson (2007) identifies three types of large-scale clandestine delivery: