Law enforcement is the next element of the criminal justice response; its purpose is to prevent, detect and investigate firearms offences. It is vital that States, and in particular those practitioners working in the criminal justice system, are able to respond effectively to firearms crimes, regardless of the context in which they occur.

An effective criminal justice response ensures practitioners receive tailored support and advice, for example: training to improve and apply their investigative skills, specialized training to operate equipment when marking, tracing and record-keeping, or to ensure the safe storage of seized weapons (UNODC, 2018c).

The success of the criminal justice response depends on many factors, among others the availability of resources, as well as the level of training of criminal justice agents. It is imperative that there is close cooperation between law enforcement agencies and all levels of government, along with partner organizations and agencies at national, regional and international levels to effectively and efficiently address firearms crime (INTERPOL, 2011). Improving the investigative and detective capabilities of the criminal justice system, combined with efforts to improve cooperation, contributes to an increased understanding of the role of firearms, thus helping to deter, detect, punish and prevent firearm offences.

As was seen in the previous section, firearms control must apply at all stages and throughout the lifecycle of a firearm, in order to prevent abuses and their diversion into the illicit circuit, not only when firearms are actually used in crime.

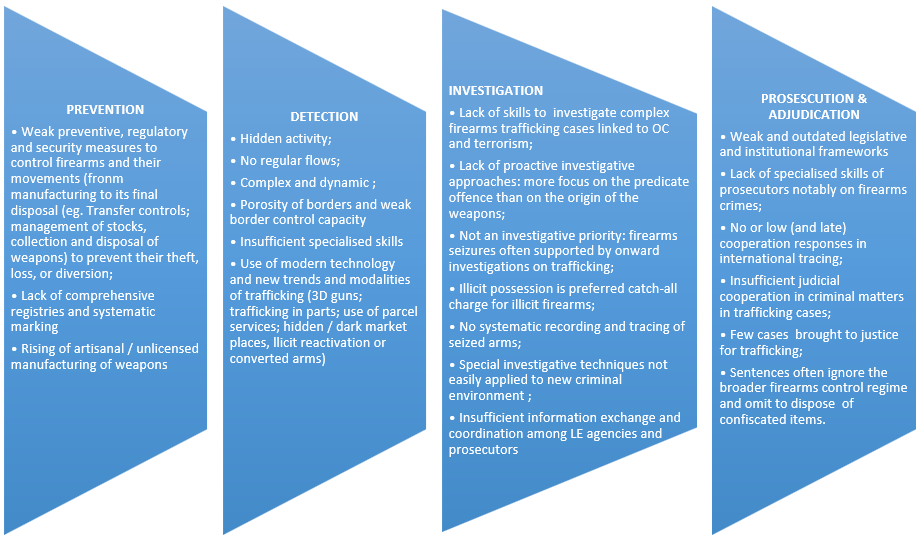

However, more than for other illicit trafficking commodities, countering illicit firearms trafficking and misuse presents numerous challenges and obstacles along the entire criminal justice chain, at both national and international levels. This partially explains the low level of cases investigated and prosecuted on the grounds of illicit trafficking, setting major challenges, as Figure 8.2 above summarizes.

Prevention focuses on ensuring compliance with existing legislation and takes many forms. In the field of firearms, preventative measures take place before and during the processes of manufacturing, possession, transfer and disposal of firearms.

During manufacturing, regular inspection of firearms are required to confirm that markings have been properly placed, the produced types and quantities are within the scope of the licence, proper record-keeping procedures are in place and all products, including firearms’ parts and components, are accounted for. These security measures are needed to prevent theft. In addition, firearms manufacturers are encouraged to develop methods that prevent the removal of markings.

There are several criminal justice measures that can be undertaken to limit unlawful possession of firearms and exercise control during a licence period. National legislation has amongst others imposed the requirement to have a clean criminal record, or to undergo a medical check to prove mental and sometimes physical health when applying for a licence to possess a firearm. Police or other services responsible for issuing licences have an obligation to maintain records of the issued licences, thus accounting for firearms in civilian possession. Law enforcement authorities also undertake regular review and monitoring of issued licences to ensure those holding firearms are still eligible, or confirmation that firearms have been returned or re-registered in the case of a licence holder’s death. Other prevention measures relating to the possession of firearms are regular checks conducted by law enforcement authorities to ensure the safe storage of firearms and ammunition.

Prevention measures during transfer of firearms in import, export, transit and trans-shipment involve background checks to ensure security during transportation, and the maintenance of thorough records of the arms transfers. Law enforcement authorities assist in the process of vetting the applicants for import-export licences and to preclude linkage to organized crime or terrorist groups. They guarantee the safety of firearms during transportation from manufacturer’s site to the national border and inspect the premises of firearms importers for compliance with safety and security regulations.

The firearm reaches the end of its life-cycle through the process of disposal through destruction or de-activation. Law enforcement authorities again provide security during the transportation of firearms to the disposal location, monitor the destruction process to assure against possible theft of firearms, their parts and components, and ensure accountability through maintaining records of the destroyed firearms. They also supervise the process of de-activation and monitor the follow-up movements, including transfers between individual and legal persons, and the whereabouts of the deactivated firearms.

Trafficking of illicit firearms is by definition a transnational offence, as it requires the movement of a firearm, their parts and component, and ammunition, “from or across the territory of one State Party to that of another” (Article 3, subparagraph (e)). Proving the illicit trafficking after the firearm has already been diverted into the hands of criminals and used in crime is often very difficult, since the nexus to the cross-border movement is often broken as the person committing another crime with the firearm is often not the same as the person doing the initial trafficking. Hence, border control must be the first level of control of illicit firearms trafficking.

Border guards and customs officials play a crucial role in detecting cross-border firearms trafficking through developing and regularly updating risk analysis products and monitoring risk indicators on firearms trafficking. They profile cargo, vehicles and passengers, selectively search them, and share data with other law enforcement authorities. Their work is further supported through the development and sharing of analytical products that alert border personnel about the modus operandi employed by firearms traffickers, as well as the profiles of the traffickers and risk indicators relevant to their country and region.

The profiling work carried out by law enforcement authorities is of crucial importance in the detection of the illicit movement of firearms, their parts and components, and ammunition. This is usually performed over cargoes, vehicles and passengers, and involves the construction of a profile, which is then applied to an individual or group using techniques of data elaboration (Ferraris et al., 2013). Profiling is used for selective control of cargo, vehicles and passengers, which can result in a thorough search, and respective seizure of illegal firearms, their parts, and/or ammunition. The risk indicators which border services use vary, and can differ between countries and regions. The most common general risk indicators for travellers/drivers are presented in Figure 8.3 below.

Law enforcement authorities share the data collected on seized firearms and apprehended traffickers with other national and international institutions for the purpose of updating profiles and establishing patterns in firearms trafficking, identifying routes, improving knowledge on concealment methods used for trafficking firearms and preventing emerging security threats.

The proliferation of illicit firearms and their availability through trafficking contribute to the capacities of terrorist groups. Indeed, links between terrorism, transnational organized crime, and illicit firearms trafficking are of increasing concern (Nakamitsu, 2017), not least because they undermine the security of the citizens, and national and regional stability. It is difficult to investigate and counter firearms trafficking because it is an intrinsically hidden and potentially global activity. Moreover, its multi-dimensional and cross-cutting nature creates complexity by drawing together a variety of criminal manifestations that support or facilitate the trafficking, or help launder the illicit incomes generated by it (Nakamitsu, 2017).

Improving the ability to investigate firearms crime has the potential to prevent and significantly reduce firearms related violence, especially if the investigation is focused not only on the firearm as evidence, but also on the firearms trafficking process. Yet, often the origin of the firearm itself is not subject to investigation, thus leaving aside valuable information that can lead to the identification of sources and routing of the firearm to the end user. This is often because firearms trafficking is rarely detected when the diversion and illicit trafficking occurs, but only once the firearms have made their way into the hands of criminals that use them to commit other crimes.

At that point, the focus of the criminal justice system is on the main offence, overshadowing the original trafficking offence, which has facilitated or made the commission of the principal offence possible. The principal offence is either considered the more serious, or the ‘easier’ one to pursue, and this risks the neglect of the wider context and the potential firearms trafficking elements of the case.

‘Use of firearm’ is ‘often identified during police investigations as an aggravating factor to a primary offence rather than a primary offence in itself’ (Hellenbach et al., 2017: 190), resulting in incomplete investigations into the supply side. Failure to identify the supplier ultimately means failure to prevent the flow and misuse of firearms (Hellenbach et al. 2017). Consequently, the extent, routes and dynamics of firearms trafficking have yet to be fully explored and addressed.

In fact, experience has shown that the link between illicit firearms and transnational organized crime is often neglected by analysts, policymakers, and legislators because the relevance of firearms for the purpose of investigation and prosecution of transnational organized crime is often underestimated or not understood. Firearms suspected of being involved in criminal activities are usually seized and confiscated from suspected offenders on the grounds of ‘illicit possession’, without considering them also as potential evidence of an illicit trafficking network (UNODC, 2015). Such isolated approaches to firearms control can jeopardise global efforts to prevent and combat transnational organized crime (UNODC, Comprehensive Training Curriculum on Firearms, Module 14).

Fighting complex crimes, such as transnational organized crime and firearms trafficking, requires broad approaches that make full use of the existing capacity of criminal justice systems in order to detect, investigate, and prosecute firearms criminality. This includes a combination of conventional reactive law enforcement (retrospective tactics), and proactive cooperative enforcement measures and judicial cooperative mechanisms that use international law and effective, on-going exchanges of information and intelligence at all levels.

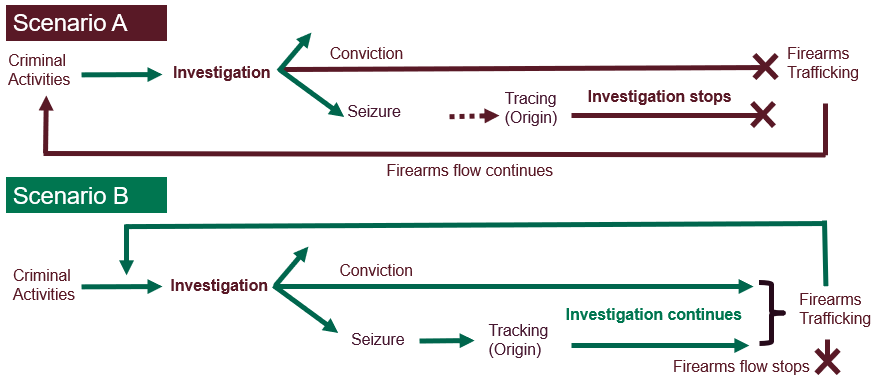

UNODC is promoting such a proactive approach to firearms investigations; one that encourages the investigation of firearm sourcing in parallel with the investigation of the main crime, and that places the firearm investigation both as a piece of evidence for the main crime, and as the object of illicit trafficking at the centre of the investigative process. Figure 8.4 presents a comparison between the two investigative approaches.

In the first scenario, the investigation is focused on the main crime, while the firearm is seized and eventually considered as an element of evidence of the principal offence. After the firearm is seized, no further tracing and onward investigation of the origin and routing of the firearm takes place. While the principal case is prosecuted and adjudicated, the firearms flows remain undisclosed and continue to supply illicit firearms.

The second scenario, promoted by UNODC, encourages opening a second investigation focused on firearms trafficking in parallel with the investigation of the main crime. In this situation the firearm is identified and traced, thus providing details on the origins, routing and persons involved in the firearms trafficking. The main crime is prosecuted and adjudicated, and, in this scenario, the firearms trafficking is also prosecuted and adjudicated, while the firearms flow is stopped. The advantage of the parallel firearms trafficking investigation is that it not only stops the illicit firearms flow and prevents criminals and terrorists from acquiring more firearms, but also contributes to a better understanding of the firearms trafficking phenomenon. The conclusions of the parallel investigation can be shared among communities of practitioners and can be used as good practices in future investigations.

This comparison emphasizes the fact that good practice involves the systematic recording and tracing of all seized firearms, and investigation into the origins of these arms.

A criminal investigation typically encompasses four stages: the initiation (also referred to as detection or triggering); the initial investigation; the follow-up investigation; and the report. Although these stages are common to all investigations, when firearms are involved, each stage presents some indicators specific to the firearms issues.

The investigation on a firearm can be initiated by direct, derived or informative triggers.

Direct investigations are triggered by events where the firearm is the main element of the primary offence. Events that trigger a direct investigation can include, without limitation, any of the main group of offences below:

Case 1: The French citizen, R.M., was accused of trafficking of illegal firearms. In the trial, the tribunal considered whether the defendant, after having bought seven shotguns in an Andorran gun shop, intended to pass them to France illegally. The Andorran police seized these firearms and a mobile phone. The defendant was sentenced to 30 months of imprisonment, the confiscation of the firearms and mobile phone, and to an accessory penalty of twenty years of expulsion from the country (Sharing Electronic Resources and Laws on Crime (SHERLOC, 2019a).

Derived or indirect investigations are triggered by events where the firearm was an accessory used for the commission of the principal crime. Events that trigger a derived or indirect investigation can include, without limitation:

Case 2: The two accused in this case were members of a street gang called the ‘Young Buck Killas', also known as ‘the YBK’. The principal aims and objectives of this gang included committing robberies and producing and trafficking drugs, mainly crack cocaine. The YBK was founded in Toronto but had extended its activities to other cities in Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. The modus operandi of the organized criminal group was to rent houses in these cities from which persons lower in the criminal hierarchy would sell crack cocaine. Members of the group transported drugs and sometimes firearms between these cities on inter-city buses (SHERLOC, 2019b).

Informative investigations are triggered by information or reports about firearms that are illicitly owned, illicitly used or are the subject of illicit transfers. Events that trigger an informative investigation can include, without limitation:

Case 3: In November 2014, law enforcement and prosecutors in Europe and the US launched Operation Onymous, an international operation aimed at taking down online illegal markets and arresting vendors and administrators of such markets. The operation was coordinated by Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre (EC3), Eurojust, the FBI, and the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) (SHERLOC, 2019c). Law enforcement agencies also made 17 arrests and seizures of $1 million in Bitcoin as well as assorted amounts of cash, drugs, weapons and computers (Afilipoaie and Shortis, 2015).

The initial investigation (also known as the ‘preliminary investigation’) is usually a fact-finding phase, often performed at the scene of a crime or incident. It is crucial to the success of the entire investigation.

Forensic experts are often called to support the proper management of the crime scene and the preservation of the evidence and its chain of custody to enable presentation in court. In addition to the general crime scene management principles – see for example, INTERPOL’s Forestry Law Enforcement Manual – Crime Scene Exploitation for Firearms and Ballistics – Guide to evidence collection and management (INTERPOL, 2018d) – there are important steps that focus specifically on firearms evidence and which include amongst others:

Where the initial investigation determines that further action is warranted, a more thorough follow-up investigation will occur, performed by a detective or other specialist, to build a stronger case including the development of a theory of how the incident occurred, and/or the identification and apprehension of the perpetrator(s).

Specifically, in connection to firearms investigations the following actions will be performed during the follow-up investigation:

This is the usually also the moment where the investigators will decide on the extent and scope of the investigation, and whether the case remains a single isolated incident or it has the potential to develop into a broader case that involves multiple cases or an international investigation, and the type of resources that it will require.

Investigation planning and management: Investigations into firearm-related crimes, especially complex and transnational cases, can require significant resources and specific investigator skills, together with the need for expert guidance and support in relation to the nature of the apparent contravention, the applicable law and relevant jurisprudence. Usually, an investigative plan is required, especially where the crimes involved are many and complex, and require international cooperation, to ensure an effective, structured approach to the full scope of the investigation.

Collection of evidence: Investigations are preliminary fact-finding exercises that primarily serve to collect and preserve evidence from crime scenes so that it can be communicated to appropriate decision-makers. There are various means by which evidence is gathered and it is important to create a record from whom the evidence was obtained and where and how it was collected. The location of the crime scene can be the place where the crime took place, or any area that contains evidence from the crime itself.

Firearms and ammunition can provide a wealth of investigative evidence that is gathered at a crime scene or in the context of searches. Specific aspects of firearms as evidence will be addressed further in subsequent parts of this Module. It is important to note that such information and evidence collection should not be limited to firearms and ammunition specific information, but should be as broad as possible and involve also information on the broader criminal context, which can provide additional leads on possible trafficking offences or links to other serious crimes.

At the conclusion of an investigation, a report should be prepared to present the facts established by the investigation process that substantiate the criminal conduct of an individual or legal entity. The report should include a description of the case, the identification details of the investigators and experts, and present all steps of the investigation. The report should reference all documentary evidence or exhibits that will sustain the facts and findings, focusing initially on the facts of the investigation and in the final section on findings and recommendations. It should be presented in an objective and non-judgmental manner, based on evidence and avoiding presumptions and speculations. The investigation should be able to respond to the basic questions: What? When? Where? Who? How and Why? It should provide the complete case picture for onward prosecution and adjudication, including the expert identification of a firearm and its ammunition, and relevant examination of its functionality.

Where no basis for an investigation is found, it is appropriate to prepare a ‘closure report’ as an alternative. A closure report should outline the facts established through the investigation process, and the reasons that the available evidence does not substantiate criminal misconduct, or the circumstances that mean continuation of the investigation is no longer possible.

While the general steps and guiding principles of all criminal investigations are similar, any investigation into the use or presence of firearms, their parts and components, or ammunition, may lead to uncovering serious and complex transnational crimes involving large-scale distribution networks. In these cases, it may be necessary to initiate multiple parallel investigations, or devise a large, single operation to develop evidence against what may be sophisticated, high-level criminals.

Typically, such investigations into firearms trafficking should transcend national borders, given the transnational nature of the crime, and involve two or more countries. Its scope should consequently not remain confined to the type of analysis that a firearm can provide as a piece of evidence for the commission of another crime. In line with the strategy adopted by UNTOC, the aim of a complex investigation into transnational organized crime should be to disrupt or dismantle major firearm trafficking networks by targeting the following levels of the organization:

The key objectives should be to target not only the material perpetrator, but also the leaders of these organizations, and to disrupt the organization by depriving them of their raw materials and assets, and any clandestine manufacturing operations that they support. This translates into the interruption of these operations and networks: