Smuggling of migrants, as defined in article 3 of the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants, is a transnational crime. It requires the procurement of the illegal entry of a person into a State. For a definition of the element of transnationality, please see Module 1 of the Teaching Module Series on Organized Crime.

Accordingly, to effectively prevent, combat and suppress smuggling of migrants it is critical that States adopt jurisdictional grounds or approaches that cover conduct that may have taken place beyond its territory. Without this approach, States may lack tools to bring to justice individuals who conduct migrant smuggling in international waters (see, for example, Box 24) or who organize or direct the operation from a third-country safe location.

Broadly speaking, the concept of jurisdiction refers to the power of a State to lawfully act, through the exercise of legislative, executive, or judicial action. There are several principles regarding States' jurisdiction, which reflect sovereign independence. For example, while States generally have jurisdiction over their territories and citizens, their jurisdiction in places outside their territory and over the citizens of other States may be more limited. UNTOC sets out a number of provisions regarding States' jurisdiction in relation to crimes under the Convention and its Protocols.

Article 15 of UNTOC requires States to provide for jurisdiction over crimes committed (i) within their respective territory (principle of territoriality), or (ii) on board a vessel flying the flag of the State concerned, or an aircraft registered under the laws of the State concerned, at the time of the perpetration of the crime (flag State principle). In addition, it prescribes establishment of the aut dedere aut judicare principle (the duty to extradite or prosecute). This means that, unless extradition is requested by and granted to another State, the State must initiate judicial proceedings against a person. The purpose of this principle is to avoid persons who commit crimes being unpunished, because there is no extradition request, or a request for extradition has been refused.

UNTOC leaves at the discretion of States the adoption of jurisdiction regarding crimes committed (i) abroad against one of its nationals by a foreign citizen (principle of passive personality) and (ii) abroad by one of its nationals, or a stateless person that at the time of events had his or her habitual residence in the State (principle of active personality). States are also free to adopt other grounds of jurisdiction.

Mother Vessel modus operandi[T]he smugglers have started using much larger boats, generally redeployed for many smuggling operations. Usually, their journey starts on a big vessel, up to 75 meters long, recycled from decommissioned freighters, whose AIS (Automatic Identification System, compulsory on any large boat) has been switched off. The effect is to make the boat electronically undetectable by the search and rescue authorities to gain time for the smugglers in case of escape, thus avoiding arrest. When the large vessel (the so-called "Mother Ship") is approaching the Italian borders, usually at about 100 nautical miles from the coasts, the migrants are transferred on smaller and cheaper boats, providing them with a satellite mobile-phone which can be used to call for rescue and sending coordinates. It must be stressed that this new method implies a greater threat for the migrants' safety in the last part of their journey, because they are left in open sea, on unseaworthy boats which are unable to reach the coast, so that smugglers can exploit the existing legal duty to aid people in danger at sea. When a distress call is transmitted, a merchant ship, being the nearest, is obliged by International Maritime Law to go and rescue, and then to disembark the migrants at the next port of call. European Judicial Training Network (EJTN), Smuggling of Migrants across the Mediterranean: a EU-wide legal challenge (2015) |

The exercise of jurisdiction at sea is a complex matter. It will not be extensively developed at this stage in the Module, but some brief introduction is provided.

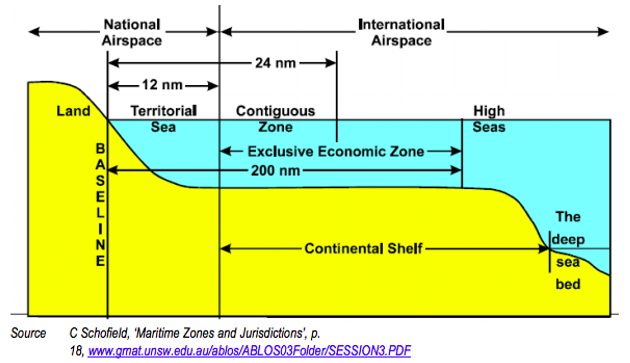

Figure 3 provides an overview of maritime zones.

Under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), States may exercise jurisdiction in the following zones, which are measured from the territorial sea baseline (TSB):

The entitlement of the coastal State to exercise its jurisdiction progressively decreases the further out from the territorial sea baseline it reaches. The following should be highlighted:

The Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants sets forth a specific framework aimed at ensuring and optimizing the exercise of enforcement jurisdiction at sea.

Article 8 Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants1. A State Party that has reasonable grounds to suspect that a vessel that is flying its flag or claiming its registry, that is without nationality or that, though flying a foreign flag or refusing to show a flag, is in reality of the nationality of the State Party concerned is engaged in the smuggling of migrants by sea may request the assistance of other States Parties in suppressing the use of the vessel for that purpose. The States Parties so requested shall render such assistance to the extent possible within their means. 2. A State Party that has reasonable grounds to suspect that a vessel exercising freedom of navigation in accordance with international law and flying the flag or displaying the marks of registry of another State Party is engaged in the smuggling of migrants by sea may so notify the flag State, request confirmation of registry and, if confirmed, request authorization from the flag State to take appropriate measures with regard to that vessel. The flag State may authorize the requesting State, inter alia: a. To board the vessel; b. To search the vessel; and c. If evidence is found that the vessel is engaged in the smuggling of migrants by sea, to take appropriate measures with respect to the vessel and persons and cargo on board, as authorized by the flag State 3. A State Party that has taken any measure in accordance with paragraph 2 of this article shall promptly inform the flag State concerned of the results of that measure. 4. A State Party shall respond expeditiously to a request from another State Party to determine whether a vessel that is claiming its registry or flying its flag is entitled to do so and to a request for authorization made in accordance with paragraph 2 of this article. 5. A flag State may, consistent with article 7 of this Protocol, subject its authorization to conditions to be agreed by it and the requesting State, including conditions relating to responsibility and the extent of effective measures to be taken. A State Party shall take no additional measures without the express authorization of the flag State, except those necessary to relieve imminent danger to the lives of persons or those which derive from relevant bilateral or multilateral agreements. 6. Each State Party shall designate an authority or, where necessary, authorities to receive and respond to requests for assistance, for confirmation of registry or of the right of a vessel to fly its flag and for authorization to take appropriate measures. Such designation shall be notified through the Secretary-General to all other States Parties within one month of the designation. 7. A State Party that has reasonable grounds to suspect that a vessel is engaged in the smuggling of migrants by sea and is without nationality or may be assimilated to a vessel without nationality may board and search the vessel. If evidence confirming the suspicion is found, that State Party shall take appropriate measures in accordance with relevant domestic and international law. |

Articles 7, 8 and 9 of the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants - dealing specifically with smuggling of migrants by sea - will be analysed in more detail in Module 3. However, given that article 8 entails provisions relating to executive jurisdiction, the following aspects should be emphasized at this stage: