In this section, the gender aspects of the roles of offenders in the conduct of Trafficking in Persons (TIP) and Smuggling of Migrants (SOM)-related activities are addressed.

Smuggling activities are diverse and involve a wide array of actors and activities from small-scale and low-profit venture, loosely connected individuals, who sometimes work on an ad hoc basis, to full-time professionals and more sophisticated organizations, (opportunistic individuals to organized criminal networks). Some of the roles are recruiters, transporters, guides or drivers, providers of accommodation, organizer/coordinator, passport or ID counterfeiters. The smuggler does not correspond to one profile, nor to one gender (see Module 15 "Gender and Organized Crime" of the Teaching Module Series on Organized Crime).

Similarly, criminal activities related to TIP may concern the recruitment of the victims (individuals, acquaintances, employment agencies, organized groups), the exploitation per se, including the control over the victim, even the use of coercion and violence, the hiding or harbouring of victims, transportation, etc.

General stereotypes about masculinity and femininity also affect the perceptions of criminality and female involvement in crime (see Module on Gender and Organized Crime). The idea of a female offender contrasts with - or goes against - ideals and archetypes about acceptable feminine behaviour. Ideas about femininity include women being more passive, with a natural (innate) propensity for nurturing and being less aggressive. If women are involved in crimes, they are commonly viewed as holding peripheral roles, often depending on their male counterparts or acting as such because of their victimization (Russell 2013; Zhan et al. 2007; Sanchez 2016). Men can be perceived as more prone to use physical violence, as leaders or as holding higher positions in the organization of the crime (Russell 2013).

From the outset, it is important to emphasize that the use of the term offender to refer to facilitator of irregular migration, in all situations, including that of humanitarian smuggling for example, is contentious. Facilitators of irregular migration may have diverse motives, all of which are not necessarily financial. When the facilitator does not seek to obtain a profit, he or she would not be considered an offender or a smuggler within the Protocol framework. National legislation, however, may differ (UNODC, 2017).

The role of females in SOM ventures has been largely absent in research in the field (Sanchez, 2016). There is an almost exclusive focus on male smugglers.

The analysis of female offenders casts light more broadly on the gendered roles in SOM. The very few studies that have looked at female offenders in smuggling activities (Sanchez 2016; Zhan 2007) have shown their role is not confined to the margins and peripheral status. According to a 2018 UNODC study analysing 100 cases of migrant smuggling or facilitation of irregular migration, women and men carry out similar tasks. Women "recruit migrants, carry out logistical tasks such as purchasing tickets or renting locations that serve as 'safe houses' prior to the migrants' arrival, obtain fraudulent documents and collect smuggling fees" (UNODC 2018, p. 53). Previous research conducted on the United States-Mexico border came to similar findings (Sanchez 2016).

Nevertheless, there is still a gender division of roles, meaning that some tasks are predominantly performed by men and others by women. For example, tasks related to the "provision of room and board, cleaning and food preparation" are often more frequently provided by women (Sanchez, 2016: 396). Women will also assume caring roles, such as taking care of vulnerable migrants, children or the elderly (UNODC 2018, p. 53). On the other side, activities related to driving, transporting or acting as a guide are mostly done by men, which does not exclude that a few women do it as well (United States-Mexico border).

Female actors remain less visible. They are less involved in large scale operations, but rather in the transportation of individuals and or small groups. They frequently work independently or in pairs. In 15 of the 100 cases analysed in the study commissioned by UNODC, women worked with intimate partners. They also happen to work with male family members. Only in two cases, women have experienced coercion on the part of their male partner to get them involved (UNODC 2018).

As men, women get involved in smuggling activities to earn money; it is a source of income. However, available data suggest that women would tend to more often be involved in smuggling for reasons others than financial gains (such as family reunification). As noted in a study on the role of women in the Chinese network of migrant smuggling to the United States (Sheldon X. Zhang, Ko-Lim Chin and Jody Miller 2007), there are 'gendered pathways' to getting involved in smuggling activities (p. 710). In that study, most women have entered the smuggling activities because of their intimate partner being already involved in the smuggling business. Others entered smuggling activities to earn money and as a means of independence (Idem).

Minors - boys and girls alike - can also be involved in the facilitation of irregular border crossings. A 2017 study has examined the realities of 'circuit minors', meaning young people who take part in facilitation of crossing the United States-Mexico borders (DHIA/UTEP 2017). While girls are also taking part in such activities, the roles remain gendered:

While the practice is highly gendered (most documented cases involve males), young women and girls are also active in the market, although their presence is considerably less visible and in fact their roles tend to be considered peripheral or unimportant (DHIA/UTEP 2017, p.3)

Box 18 covers an account from a woman who facilitates irregular migration at the border of Costa Rica. This example shows that smugglers are not all ruthless criminals. The portray that is given in this article is one of smuggling as being a business. However, the more you read the excerpt, the more you see the nuances. The woman might earn a profit, but she sees herself as a good person, and, in her words, "…I'm just helping them get to liberty, which for them is the United States.", and when remembering a message from a migrant who thanked her, she says "I feel good, feeling that it hasn't all been about money."

The lecturer could discuss this example with the students and see if their perception of the woman who facilitated irregular migration changes during the reading.

They arrive as boxes. Doña Katia's contact in Colombia calls to say, "I've got six boxes coming to you next Tuesday," and she understands his meaning. In the business of moving people illegally across international borders, discretion is required.

Still cajas, or boxes, sounds a little cold to Katia, who prefers to talk up the human element of human smuggling. So, the Indians and Eritreans, the Bangladeshis and Haitians she collects on the border where Panama meets Costa Rica acquire a new name when they travel across the latter country in her car, then board a boat to Nicaragua and a bus to Honduras, hurdling the series of borders toward the U.S. "I call them pollitos," she says. Baby chickens.

In Paso Canoas, a shabby Costa Rican border town facing Panama, at least 14 other smugglers-sometimes called coyotes-compete for the migrant trade. Katia, a mother of two, calculates that she has sneaked between 500 and 600 people through the heart of Central America in the past 2½ years. She knows her customers not by their names but by their faces, which show up on her phone in texts sent from another smuggler preparing to hand them off: brown men, and a few women, in sheepish clusters outside the Western Union where they have retrieved cash from a relative to cover the next leg. From South Asia, the journey costs anywhere from $10,000 to three times as much. […]

At base, it's a business. And Katia, as she sometimes calls herself, offers a rare view into how it works. In a series of interviews with TIME, she laid out her smuggling operation in detail, from the bribe expected at a police checkpoint in Nicaragua to the surprisingly modest monthly profit she pockets from work that outsiders assume is part of a vastly lucrative industry dominated by hardened criminal gangs.

So, there was a logic to finding, on an overcast December afternoon in Costa Rica, a tall, brown-eyed man from Punjab standing beside the Christmas tree in Katia's living room.

The journey of Mulkit Kumar began a month earlier, in a northeastern India village that's small but hardly disconnected. To see his wife holding their baby in the house he left, the construction worker presses the video icon on his smartphone. When he decided to leave that house for good, he used that same phone to dial a number in New Delhi. "Friend of a friend," Kumar says of how he found the first smuggler. "There are a lot of people who have made the journey before."

We are all in Katia's house, a modest bungalow built with her earnings as a coyote, alive with her niece's chatter and her son's PlayStation, when her own phone rings. She yelps. It's the Delhi contact. "I already withdrew the money," she tells him. "My love," he coos in reply, in Hindi-accented Spanish.

"Yes, I'm a good person," she says. "Friday I will get the guy out, and then the following week I'll get the other guys who are coming from Ecuador."

Between them, the two smugglers arranged most of Kumar's journey, which will be financed - as most migrant travel is - by the traveler's extended family. Relocating a wage earner to a country with much higher wages and the prospect of upward mobility amounts to an investment, and a sound one. The transplant will wire home a few hundred dollars a month, likely for decades.

Kumar says his four sisters came together to cover his expenses: 140 rupees ($2) for the bus ride to Delhi and 60,000 rupees (about $950) for the airfare to Quito, the capital of Ecuador. Smugglers say that if you want to go to the U.S., start by booking a ticket to Quito. Ten years ago, the South American nation threw open its doors to the world, requiring no visitor to arrive with as a visa. And though the policy has tightened some since, the reputation endures. The border of Colombia lies just 150 miles away, and from there it's a couple days up the Central America trail to the edge of North America.

The journey is life-changing, fraught - and routine.

But traveling through the Americas is no snap. Near a poster bidding tourists Dare the Darién, an Ecuadoran migrant recounted attempting the journey four times with no success, paying $300, $200, $150 and $200, only to be sent back. He was about to try yet another coyote. "When the things are legal, you can look into the details," he explains. "But when it's illegal, it's a risk you have to take."

Things are getting tougher. […]

Sure enough, in Costa Rica, Katia keeps doing business. It's not like a year or two ago, when she might have seen as many as 35 migrants a day. Those were flush times: the U.S. had given temporary protected status to Haitians because of the 2010 earthquake and took a softer line on Cubans because of Castro. The door closed when the Obama Administration changed the Cuba policy, but the route remains popular, mostly with South Asians. Of the 235 detainees in the Panamanian camp where Hussein was briefly held, 185 were from India.

"You try to do excellent work and lower your prices, so you can keep business going," Katia says in her bungalow. She snagged the Delhi contact by undercutting his previous Central American smuggler, who charged $2,700 per migrant. "I'll give you better rates," Katia said, offering $2,300.

"He gets them from India to Ecuador, and I get them from Ecuador to Mexico," she says, and launches into a description of her enterprise. From Quito, migrants go by bus to Tulcán, the city in Ecuador nearest to the Colombia border. There her contact meets them, and arranges transport north to Capurganá. When they emerge from the Darién, they travel by taxi to Panama City, then are directed to a bus. "There's a compartment in the bus where they hide," Katia says, "and the bus brings them here."

"Here" is the strikingly informal boundary where Panama meets Costa Rica. (In some places, it's simply a median between parallel highways.) Still, she arranges crossings into waiting taxis at 3 a.m. and posts a lookout, because what she's doing is illegal, though she has a hard time regarding it as immoral. "If I was making them do something they didn't want to do, that'd be different," Katia says. "But I'm just helping them get to liberty, which for them is the United States." […]

Such stories are not rare. But researchers say brutalizing the customer does not work as a business model, especially in the age of social media. Katia, like her contact in Delhi, isn't even a full-time smuggler; each has a day job in transport. […]

Katia's monthly income from smuggling averages $800-the same as from her day job, she says. "They make what everybody else makes," says Gabriella E. Sanchez, a research fellow at the Migration Policy Centre at the European University Institute. "People don't want to hear that. This notion of organized crime has never been further than the reality of the facilitation we see around the world."

Illusions die hard, though. In her living room, Katia beams while recalling an email from a onetime customer thanking her for helping him get to the U.S., where he opened a pizza parlor. "I feel good, feeling that it hasn't all been about money," she says. But that extra $800 a month let her move into a house she built; it paid for the video console her son toggles from across the room and family trips to a water park. It also explains why she got up in the night to gather the 18 Africans whom her mendacious new drivers had dropped by the side of the road, a five hours' drive from the border with Nicaragua. Collecting them was the right thing to do, but she also needed the reference.

"Yes," she says. "They recommend me to their friend!" A satisfied smile. "Business."

To propose a nuanced picture on smugglers, the movie 'Frozen River' that talks about the involvement of two women in the irregular crossings between Canada and the United States, is also proposed in the Additional Teaching Tools. It is a movie on native women's experiences in smuggling and their criminalization.

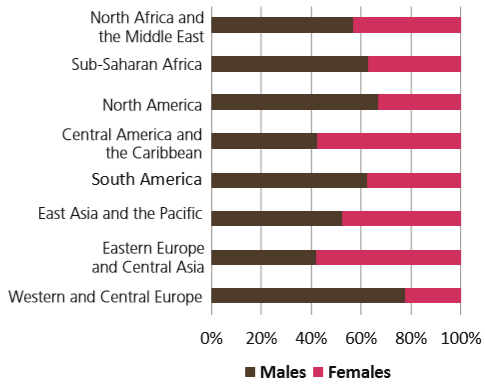

Most persons convicted for TIP offences are men. However, the number of women among traffickers is significant, representing 38 percent of all persons convicted of trafficking. According to available data on crime, female involvement in TIP is higher than for other types of crime (UNODC Global Report on TIP, 2018). Indeed, according to the United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems (2006-2009), the average share of reported female offenders for all types of crime is 12 per cent (of convictions) (cited in the UNODC Global report on Trafficking in Persons 2012, p. 30).

According to the analysis of case law and from qualitative studies, three common trends and features emerge (UNODC, 2018). First, women are commonly involved in the trafficking of other women and girls, and their involvement is often related to the recruitment, mostly for sexual exploitation. Hence, the fact of sharing the same gender can be used to facilitate and establish trust with the potential victim since a woman may be seen as less threatening (UNODC 2018).

Second, another pattern that has been documented is that of women and girls who have been themselves trafficked and later become involved in the trafficking of others (women and girls). Existing qualitative analysis of such dynamics - former victims who become perpetrators - suggests that the motivations include ending the exploitation or lessening the level of exploitation and improving their position in the relationship with the traffickers or reducing their debts towards the traffickers (see UNODC Global Report on TIP 2018, p.6; Kienast et al., 2014). In some situations, women and girls can also hold dual and conflicting roles: that of being a victim of violence at the same time as a perpetrator. Third, traffickers working as a couple, which can be used in the recruitment phases to entrust the potential victims, is another scenario that has been documented (UNODC, Global Report on TIP, 2018).

However, an analysis of court cases also illustrates that women can have central roles, and even leading roles in the planning and organization of the crimes of trafficking. Some trafficking networks were female-led. For example, in a study conducted by UNODC on 155 trafficking cases, 54 percent involved female traffickers.

An example of women playing an active role that has been studied and received quite a lot of attention, is that of the so-called Madams in the trafficking of women and girls from Nigeria to Italy or other European countries (and the term madam is also used in other regional contexts). However, here again, it is important to highlight that instances of trafficking occur within the broader phenomenon of sex work migration. Indeed, not all situations of Nigerians who migrate to work in sex work is a situation of trafficking (See Plambech, 2017). Madams can play a diversity of roles, from the recruiting phase, the organization of the migration, or being the contact person once in the country of destination who will have a role in supervision, including control and exploitative practices. Madams often were themselves sex workers, or in the case of trafficking, a trafficking victim, before taking a role in the organization.

However, male offenders remain the clear majority of traffickers. In cases of TIP for sexual exploitation, one tactic that has been documented is the feigning of a romantic relationship as a means of recruitment, building trust and an emotional connection, to then turn the relationship into one of exploitation. It generally involves a male perpetrator and a female victim (UNODC 2014, p. 32), often underage girls but also adult women. Deception is often used in cases of TIP; for instance, deception regarding the work conditions (e.g. salary, working hours) and the type of work. In the case of feigned romantic relationships, the perpetrator deceives the person by pretending to start a love/intimate relationship. It helps to win the trust, and progressively, through manipulation and coercion, exploitation for profits starts.

This type of situations, and of relationship with the exploiter, has generated a lot of interest in the literature on TIP, in particular for domestic TIP (i.e. no border was crossed). It has led scholars to warn that such emphasis fosters a narrative, an unidimensional explanation of a path leading to TIP for sexual exploitation: ruthless pimp/lover lures girls and young women. It once again tends to portray girls and women as passive victims and neglects other factors and constraints from the social environment. The trafficker does not act in a social vacuum.

One element to raise though is the relational dimension between the trafficker and the person being exploited. As stated in criminological research, the reductionist and simplistic view on the victim of trafficking, tends to obscure the complex interactions that can occur with the trafficker (Kleemans 2011). The relation aspect is also important regarding trafficking in domestic work. There might be family ties, direct or indirect, with the exploiter. There also may be a sense of gratitude if the exploiter has 'helped' the person to migrate and settle in a new place. There is often a power imbalance and dependency as a result.