This section presents a global overview of Trafficking in persons (TIP) and Smuggling of Migrants (SOM) while acknowledging the limitations and shortcomings of such an exercise. It is crucial to emphasize that data on these crimes must be used with caution. The numbers provided are based mostly on the UNODC Global TIP reports (especially 2016) and the first UNODC Global Study on SOM (2018). The numbers and statistics on TIP gathered in the UNODC Global report, for example, correspond to detected and identified cases of trafficking, victims, and offenders. As such, it does not represent estimates of the scope or the scale of TIP worldwide. On the topic, you can also consult the UNODC research brief on Multiple Systems Estimation (2016). On the methodology used in these documents, see UNODC's Global TIP Report 2016, Annex I, and Global SOM Study. There are still numerous gender gaps in the data and knowledge available. Regarding SOM, there is scarcely disaggregated data by age and sex. Regarding TIP, there is no mention of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) persons.

Among the first questions raised when discussing TIP or SOM are the extent of these phenomena. How many victims of trafficking are there worldwide? Who are the victims? Who are the traffickers? How many migrants cross the borders with the help of smugglers? Who are the smugglers? These are legitimate and important questions for any social inquiry. However, data collection on these issues is difficult, and available data can hardly provide us with an accurate picture of the realities of TIP and SOM.

First, data collection is determined by definitions (who to count in) and, both in the field of trafficking and SOM studies, there are debates and contentions. The migrant smuggling figures are often conflated with irregular migration data. There are also different legal definitions in national legislation, as well as variations concerning the interpretation of the offence.

Second, being two types of crimes, TIP and SOM are related with illegality and thus hard to observe. Reported crimes represent only a fraction of the scale of crime occurrence in societies. In addition, differences across countries may reflect not only differences in legal definitions, but also the capacity of criminal justice systems to identify and investigate. In turn, detection by law enforcement is influenced by political priorities (e.g. to deter sex work, to deter irregular migration) and levels of awareness, which will impact on the resources and efforts being mobilized to, pro-actively or not, facilitate the identification of trafficking victims for example. As an illustration, in a given country, if an increase is reported in the number of identified cases of labour trafficking, it may reflect more awareness towards the issue, rather than a rise in its occurrence.

The latest UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (2018) covers 142 countries and to a great extent, data come from national authorities (with few exceptions when the data are from international organizations).

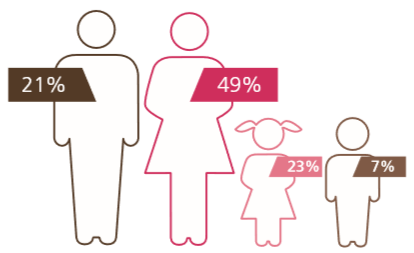

According to the data collected in the UNODC Global Report on TIP (2018), 72 percent of identified victims of TIP are women and girls, respectively 49 percent are women and 23 percent are girls. The main form of trafficking affecting them is sexual exploitation, which has remained constant over time, although there are some regional differences. Since UNODC started collecting data on TIP in 2003, females have always represented the majority of victims. However, there has been a decrease in the number of women, alongside an increase in the number of girls, as well as an increase in the number of male victims.

Children form, after women, the second most important groups of detected victims of trafficking, with 30 percent in 2018 (boys and girls).

The data gathered in the UNODC Global report suggest that in certain regions, children represent a much higher proportion of detected victims, such as in Sub-Sahara Africa, where children represent more than 50 per cent of trafficking victims. However, the issue of definitions may impact on data collection. As outlined by scholars, children mobility and child labour migration are often framed and understood as being a form of trafficking. This framing may obscure and neglect the complex realities of youth mobility for labour under different structural constraints (Huijsmans and Baker, 2012; Okyere, 2012; Howard 2014, 2017; Howard and Boyden 2013).

Trafficking for sexual exploitation and for forced labour are the most common types of trafficking being reported and identified. There is a sharp gender differentiation between the two - when looking at global data. Global data suggest that 82 percent of men are trafficked for forced labour, and 10 percent for sexual exploitation (UNODC Global Report on TIP 2018), and in the case of women in 83 percent of cases it is for sexual exploitation (UNODC Global Report on TIP). However, women and girls are also victims of other types of trafficking: sham or forced marriages, begging, forced labour in different sectors (domestic work, agriculture, catering, garment factories, cleaning industries), as well as organ removal. Women and girls also often suffer sexual violence as part of the exploitation. However, it is important to re-emphasize that if trafficking is still more readily associated with sexual exploitation, then more efforts and attention will be dedicated to identifying such cases, and TIP for sexual exploitation might therefore be over-represented.

Trafficking for forced labour encompasses different labor sectors: domestic work, agriculture, fishing industry, catering services and restaurants and hotels, construction, cleaning industry, etc. There are gender differences between different labour sectors, given the gender division of labour. Some labour sectors still today comprise more men (such as construction) or women (such as domestic and care work).

For example, trafficking in domestic work is known to affect predominantly women and girls. Domestic work is a highly gendered labour sector. The International Labour Organization (ILO, 2013) estimates that 83 percent of domestic workers worldwide are women and girls (and there are an estimated 52,6 percent million domestic workers). Literature on domestic work has demonstrated that it is a sector particularly at risk of exploitation (the topic of domestic work will be further discussed in this Module, in the section on 'TIP and migration').

Another form of trafficking that affects disproportionally (almost exclusively) women and girls is trafficking for forced marriage. However, there is no consensus on whether forced marriage would classify as a form of trafficking (it is not included as a form of trafficking in all national legislation). Hence, data on the topic must be used with caution. According to the data collected in the Global Report on TIP, different situations may be included under this form of trafficking: organized fraud schemes related to irregular migration, practices of child marriages or marriage without the woman's consent, and even the trade of women for marriage (UNODC Global Report on TIP, 2016 and 2018). These practices have been reported worldwide and are not limited to a few countries. It is important to note that sham marriage does not equate with forced marriage and trafficking. Sham marriages are marriages where the purpose of the marriage is not to live in marriage with the other person but to serve a different purpose, such as migration into a country.

While it is crucial to acknowledge situations in which women and girls are forced into marriages that may be violent and abusive, it is equally essential not to reinforce the image of women as being solely passive victims. Women (as well as men) may willingly engage into sham marriage for several reasons, including as a mean to facilitate their mobility. See for example the work of Kyunghee Kook on the experiences of North Korean escapees toward China. In her article "I want to be trafficked, so I can migrate: Cross-border movement of North Koreans into China through brokerage and smuggling networks", the author explores North Korean escapees' migration to China, their motivations to leave and the blurred linkages between trafficking and smuggling. (Kook 2018).

Child labour may be found in numerous sectors, mines, construction, fishing industry, or domestic work. Children can also be exploited through forced begging. Involving both boys and girls, this type of exploitation has also been reported and studied in various parts of the world, such as the exploitation of the Talibé in Senegal (HRW 2017), as well as in India, Albania and Greece (just to name a few) (see Save the Children 2007; Anti-Slavery International 2009).

In the United States, Human Rights Watch has published a report on the working conditions of children in the tobacco industry. The report " Tobacco's Hidden Children: Hazardous Child Labor in US Tobacco Farming" documents, among other things, long working hours without overtime pay, health problems related to nicotine exposure (poisoning) as well as work safety issues (see HRW 2014). These are only a few examples.

Some examples of TIP from different countries are presented below to show the distinct types of TIP. Lecturers are also encouraged to use the UNODC SHERLOC Case Law database to select other cases of trafficking in the country and region of their choice.

The first two examples involve men as victims in two different labor sectors and regions.

The example in Box 9 is the first successful conviction of trafficking for forced labour in Canada, which involved the exploitation of migrant workers in the construction sector by members of a same family (R. v. Domotor case).

All the accused were immigrants from Hungary and related to one another by birth or marriage.

All the alleged victims were Hungarian nationals (of Roma background) recruited in Hungary. None of the victims spoke any English.

The victims had all been relieved of all their travel documents by their Canadian hosts and were taken to various banks to open bank accounts and to obtain access and debit cards. These items were confiscated from them. They were then prompted to file refugee status claims based on fraudulent accounts of having been persecuted in Hungary because of their ethnicity. They were then taken to local social services agencies to apply for monetary assistance. Money received from this source was retained by the accused. They were employed as laborer in construction businesses operated by some of the accused and not compensated or minimally compensated for their labour. Although the victims were housed and fed, it appears that they were subjected to intimidation and that their ability to move within the community was controlled. They were threatened with physical violence and death, as were their relatives in Hungary. Several of the recruits were told to participate in the theft of mail from Canada Post mailboxes. The objective was to obtain checks from the mail, negotiate them by depositing them to bank accounts, and later withdrawing the cash. It is estimated they obtained CAD1,000,000 using this method.

The accused profited from this human trafficking enterprise through the unpaid labour of the recruits, by retaining social assistance payments intended for others, and very substantially through the theft of checks from the mail.

Another example of trafficking for forced labour involving men concerns the fishing industry. Recently, more attention has been given to trafficking in the fishing industry, notably in South-East Asia. While far from being the only country where exploitative practices occur in this labor sector, the following example concerns Thailand. The case example is taken from Human Rights Watch, providing insights from the workers' experiences. HRW has produced a report as well as a video (see Additional Teaching Tools).

In 2011, Saw Win, 57, migrated to Thailand to find a job, hoping to earn money to send to his family in Burma. He told Human Rights Watch that he traveled with a broker he had met in the town of Kawthaung at the southern tip of Burma, who said he would get him across the border and secure a food processing job that would pay 150 baht (US$4.50) a day. However, once he reached the Thai side of the border, Saw Win was put in the cargo bed of a truck, sandwiched between other undocumented migrants. It was difficult to breathe, especially when smugglers covered them with tarpaulin to hide them from police checkpoints. […]

When Saw Win arrived in Kantang, a port town in Trang province on Thailand's southwest coast, he was confined to a room with 40 other men. In the morning, the men were separated and sold to different brokers controlling migrant crews working at the town's various fishing piers. Saw Win said he worked on a trawler with no pay for three months.

He assumed he would be set free when the boat returned to port, but the broker's men were waiting at the pier and locked him away again, this time for three days. Saw Win's broker then sold him to a boat in Songkhla, on Thailand's southeast coast. A carrier boat transported him into the South China Sea where he was forced to board a purse seiner fishing illegally for mackerel in Indonesian waters […] "Payment" was meager amounts of food, withheld if the skipper did not think the crew had worked hard enough. Some men became malnourished and seriously ill, contracting diseases like scabies. […]

Saw Win was eventually sold at sea to another Thai purse seine boat. By now valued as a more experienced crew member, he was physically abused less than others. […]

One night, Saw Win decided to jump overboard near the Malaysian coast. Luckily, another passing Thai purse seiner plucked him from the water and concealed him on the boat.

Soon afterward, he set foot in Malaysia, his first time on land in almost two years. Saw Win eventually returned to his home in Burma, but he had lost several years of earnings, and local wages were too low to support his family. He returned to Thailand, this time bringing several family members with him. […]

Saw Win said he wished that more established Burmese migrants in Thailand would stop acting as brokers and profiting from abuse of fellow Burmese; that the fishing industry would stop relying on underground brokers profiting off the mistreatment of migrants; and that the Thai government would start listening to the organizations acting on behalf of the rights of workers.

The following example concerns domestic work and involve young women who were under 18 years old when the exploitative situation started. The case stresses different elements of vulnerability that can be taken into consideration: the youthful age of the victims, the family ties with the perpetrator or the informality of the first arrangement, and the fact of being a newly arrived migrant.

The case will be used in one of the exercises for this Module to identify, through a gender and intersectional approach, key factors that have increased the vulnerability to TIP, such as:

The applicants, two sisters, are French nationals, who were born in 1978 and 1984 respectively in Burundi. They left that country following the 1993 civil war, during which their parents were killed. They arrived in France in 1994 and 1995 respectively, through the intermediary of their aunt and uncle (Mr. and Mrs. M.), Burundi nationals living in France. The latter had been entrusted with guardianship and custody of the applicants and their younger sisters at a family meeting in Burundi. Mr. and Mrs. M. lived in a detached house in Ville d'Avray with their seven children, one of whom was disabled. The applicants were accommodated in the basement of the house and alleged that they were obliged to carry out all household and domestic chores, without remuneration or any days off. C.N. claimed that she had also been required to take care of Mr. and Mrs. M.'s disabled son, including occasionally at night. The applicants allege that they lived in unhygienic conditions (no bathroom, makeshift toilets), were not allowed to share family meals and were subjected to daily physical and verbal harassment.

Relying on Article 3 (prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment), V. alleged that she had been subjected to ill-treatment. Under Article 4 (prohibition of slavery and forced labour), the applicants submitted that they had been held in servitude and required to perform forced or compulsory labour. Lastly, relying on Article 13 (right to an effective remedy), they also claimed that no effective investigation had been carried out in response to their allegations.

The Court held that France was to pay C.N. 30 000 euros (EUR) to cover all heads of damage.

In the case of SOM, the Global Study on SOM (2018) relies on a review of existing data, also, and provides some estimates.

Data on SOM are limited. At a global level, there is no statistical analysis on smuggling of the same extent than what we can access on TIP. The Global Study on SOM (UNODC 2018) is based on the review of available data worldwide (mostly coming from national authorities and international organizations) and provides some estimates about the number of migrants using smuggling services in different regions. Specific migration routes are identified as smuggling corridors.

For example, the estimates presented in the UNODC Global Study situate at 375,000 the number of smuggled migrants on the three Mediterranean routes (East route - toward Greece, West route - toward Italy, and Central route towards Spain), and the number of those traveling along Sub-Saharan countries to North Africa at 480,000. In the case of North America, the number is in the 735,000 and 820,000 range, and 550,000 from neighbouring countries to Thailand (UNODC 2018).

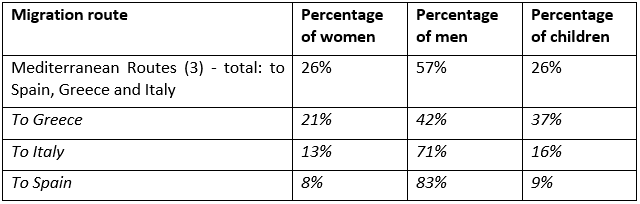

None of these are precise figures. Furthermore, there are scant data disaggregated by sex and age. When available, data indicate that most migrants tend to be young men. The gender composition of irregular migrant flows may vary according to trends of mobilities in a given region or for a given nationality. On certain routes, there are more women, more unaccompanied minors or more family units (UNODC 2018). For example, the differences between the data on irregular migrant flows to Greece, Spain, and Italy, in table 1 below reflect that on the Eastern route toward Greece, the majority were Syrians migrating in families (74 percent, p. 37). On the Central Mediterranean route, toward Italy, and the Western route to Spain, most migrants were young men.

Similarly, from the Horn of Africa to Yemen, available data suggest that males represent 83 per cent of smuggled migrants (UNODC 2018), and from Central America to the United States the estimate is about 75-80 percent (UNODC 2018).

Among migrants using smuggling services, there are children who may travel with their families and many others who are unaccompanied or separated children. The presence of children in situations of irregular migration poses challenges to the protection of their rights and their well-being. Numbers indicate that most minors who migrate unaccompanied are boys between the ages of 14 and 18 (UNODC 2018). However, empirical data suggest that on many occasions, children may travel in the care of friends, distant relatives and smugglers themselves, who are paid a fee in exchange for caring/protection.

In the European context and the smuggling flows through the Mediterranean, the number of children refugees and migrants, notably unaccompanied, have reached unprecedented levels. In 2016 alone, the number of unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) who arrived in Greece, Italy, Bulgaria and Spain was 34,000. Italy has received the highest number of UASC, namely 25,846 in 2016, and 15,779 in 2017, representing respectively 14 per cent and 13 percent of the total number of migrants arriving via the sea. While Greece has received a far larger number of child migrants and refugees, for a total of 63,920 in 2016, the majority (92 percent) were accompanied (UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM, 2017). In Italy, it is the opposite, whereas 91 percent of children who arrived by sea in 2016 were unaccompanied (UNHCR, Italy - Unaccompanied and Separated Children (UASC) Dashboard January - December 2016). The majority of UASC arriving in Italy are boys, aged between 15 and 18 years old (between 92 and 93 percent) (UNHCR/UNICEF/IOM, 2017). The Central Mediterranean route to Italy (mostly departing from Libya) has been characterized by the widespread violence used against migrants in Libya. Children and, even more so unaccompanied children are at increased risk of exploitation and abuse. The results from a survey conducted with children and women refugees and other migrants in Libya (122 participants) indicate that three-quarters of the children refugees and migrants had experienced violence, harassment or aggression at the hands of adults, and almost half reported sexual violence or abuse during the journey (UNICEF 2017). According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), on the central Mediterranean route, on average, children report more often indicators of exploitative practices (96% of children versus 76% of adults), which suggests that they are much more vulnerable to experiencing violence along their journey (IOM 2017a: 4).

While smuggling is not always associated with violent practices, it is acknowledged that migrants face many risks and are more vulnerable to violence and robbery (UNODC 2018). Violence can be perpetrated by smugglers and/or other criminal gangs along the smuggling routes. Different forms of severe violence have been reported, such as extortion for ransom, forced confinement, forced labour to repay the debt, killings and many other forms of abuses. Sexual violence (including sexual assault and/or intimidation) is also common.

Gender-based violence (GBV) is among the root causes of Trafficking in Persons (TIP), as well as part of the realities and experiences of TIP and Smuggling of Migrants (SOM). It is an important aspect to understand when considering the gender dimensions of TIP and SOM.

The terms gender-based violence (GBV) and violence against women are often used interchangeably. However, GBV is broader and includes all types of violence perpetrated based on gender norms and unequal power relationships. The focus on the violence against women does not exclude the fact that men and boys can also be victims of violence. However, it is still women and girls who are disproportionally affected by violence because of their gender, and unequal power relationships (see also Module Series on Integrity and Ethics, Module 9 on Gender Dimensions of Ethics). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) persons are also victims of violence on grounds of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or sex characteristics.

GBV is an umbrella term for any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person's will and that is based on socially ascribed (gender) differences between females and males. The nature and extent of specific types of GBV vary across cultures, countries and regions. Examples include sexual violence, including sexual exploitation/abuse and forced prostitution; domestic violence; trafficking; forced/early marriage; harmful traditional practices such as female genital mutilation; honour killings; and widow inheritance.

From the definition above, it is evident that the sexual orientation and gender identity dimensions are not included. Below is a definition used by UNHCR, which provides a broader frame in terms of gender power inequalities at the roots of GBV.

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) refers to any act that is perpetrated against a person's will and is based on gender norms and unequal power relationships. It encompasses threats of violence and coercion. It can be physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual in nature, and can take the form of a denial of resources or access to services.

Along irregular migration corridors, sexual violence (including sexual assault and/or intimidation) is common. Sexual violence against women and girls has been reported widely in different regions of the world: from Africa to Europe, to South Africa, to the Middle East, in the Americas and within the European Union (See UNODC Global Study on SOM, 2018). However, while less visibility is given to it, and scarce data is available, sexual violence is also used against men, not solely against women, along all migration corridors.

Regarding TIP, sexual violence is part of TIP for sexual exploitation or the exploitation of the prostitution of others. While most identified victims of TIP for sexual exploitation are females, victims can also include men and boys, and LGBTI persons. In addition, victims of other forms of exploitation, such as forced labour, can also suffer sexual violence at the hand of their exploiters.

For example, a study on the conditions of migrant women working in agriculture and the vulnerabilities to trafficking in Italy has documented instances of sexual blackmailing being used by employers against the women working in the greenhouses (in the region of Ragusa, Sicily). Employers used different forms of pressure to obtain sexual favours, such as the risk for the migrant worker to lose her job if she did not go along with the requests:

As the president of Proxima told us, most of the cases of concern involve women who live on area farms with their children. For example, Luana, one of the women helped by Proxima, used to work and live on a small farm near Vittoria with her young daughter and son. Every day, the employer took her children to the area school, which was far from the farm. In exchange for this 'favour', he asked Luana to have sex with him. In order to protect her children and keep her job and accommodation, she accepted this situation. (Palumbo and Sciurba 2015)

Another example concerns a case of a successful conviction on charges of trafficking which also included sexual violence, and consequently a conviction on charges of rape.

Key facts

A Moroccan girl migrated to Belgium to live with a Belgian man and help with domestic chores. The man used the false promises of marriage and that the adolescent girl could pursue her education. Once in Belgium, the girl was compelled to have sexual intercourse with the man, as well as perform domestic work for him and the mother, without receiving any pay. She was also physically abused both by the men. The girl was a minor when the situation was initiated.

Legal Reasoning

With respect to the claim of human trafficking, the Court found that the defendant had taken advantage of the victim's vulnerable position, since she was staying illegally in the country and she was a child. The Court also relied on the reports of a psychologist and a forensic psychiatrist to come to these conclusions. The fact that the defendant hit the victim and lied to her and her family about his intentions to marry the victim, were also considered to be aggravated circumstances. The victim's testimony where she stated that she was not forced to work, but simply did it out of boredom, did not alter the findings of the Court. Finally, the defendant's argument that the victim's mother had agreed to him taking the victim to Belgium, and that the victim's sister and her husband had passively cooperated, was considered irrelevant by the Court, since these actors were deceived by the defendant.

Regarding the second charge of engaging in sexual relations with a minor, the Court found these allegations to be proven based on the statements made by the victim. The lack of a DNA-investigation was not considered relevant in that sense.

When determining the appropriate sentence for the defendant, the Court considered the fact that the defendant is a lawyer and considered that he had seriously breached the oath he took as a lawyer.

See the special issue on GBV at work, on the Beyond Trafficking and Slavery Blog to find other examples.