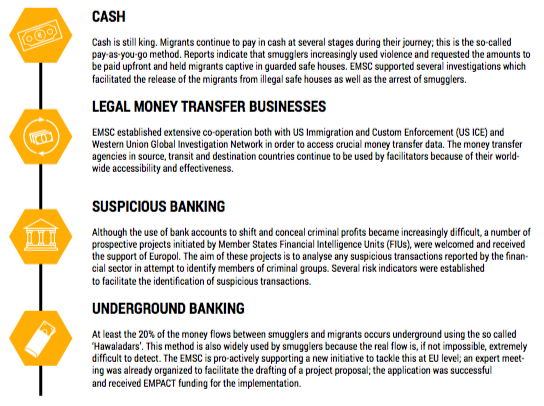

As noted earlier, in many cases financial investigations are essential to detect and punish smugglers. Hence, the critical role of FIUs in suppressing migrant smuggling. The variety of methods by which payments are made and through which money circulates in the context of migrant smuggling ventures vary considerably. Financial investigations will concern the gathering of information and collection of evidence - and respective analysis - regarding proceeds of smuggling of migrants. They will focus on evidence that reveals cash flows and money trails, for example bank accounts and wire transfers, credit card reports, money transfer slips (such as MoneyGram) and Hawala system records (see Tool 7 Law Enforcement and Prosecution, UNODC, 2010).

Challenges in financial investigations - Hawala systemIn the case of Hawala, collection of evidence can be particularly challenging. An interesting case was reported during a UNODC expert group meeting on Financial Investigations held in November 2018. An officer at the Austrian Financial Intelligence Unit presented a case of migrant smuggling in which Hawala was used to transfer more than EUR 6 million. Migrants were smuggled from Iran and Iraq to Austria and Germany. The payment was released after the migrant smuggled had reached the destination he paid for. After a few months of investigation, the law enforcement conducted five house searches and seized a considerable amount of cash and goods. They also found a notebook, used by a hawaladar, to keep track of the transactions done in this context. The same officer underlined that hawala system is still not very well known and understood although widely used, with an estimate of USD 202 billion fund transfer worldwide. Although it is not illegal per se - in some national jurisdictions the use of hawala is legal -, the hawala system is used to facilitate money flows in transnational organized crime offences, including in human trafficking and migrant smuggling. |

Migrant smuggling is a crime for profit. This is the motivation of smugglers. Following the money will likely lead to the leaders of organized criminal groups.

Accordingly, financial investigations should run parallel to smuggling investigations and be launched as early as possible. Effective financial investigations require staff with strong analytical and technical skills. National laws will necessarily need to be examined as they impact on the scope of the investigation. Rules on banking secrecy might be critical. Privacy concerns must also be examined, as there is always a risk of evidence being deemed inadmissible. A successful financial investigation will lead to the identification of proceeds of crime and their seizure, and possibly also to the identification of high-level organizers. Likewise, it will identify important assets to be confiscated, namely those used in, or which facilitate, the commission of the crime (article 12 of UNTOC).

HKSAR v L.H.K. Criminal Appeal No. 84 of 2003FACTS On 12 March 2001, police officers searched the defendant's home in Mongkok (Hong Kong, China). They were looking for the defendant's elder brother (L.H.L.2) and his girlfriend (C.S.P.) suspected of money laundering and migrant smuggling. The police found 25 Japanese passports and 97 unlawfully obtained Chinese passports as well as a false China mainland immigration stamp. It was ascertained the Japanese passports had either been lost by their owners or stolen. (…) In the defendant's room were found several bank passbooks. It was later determined that the defendant had opened one HSB account on 14 October 1998, and one HSBC foreign currency account on 23 October 1995. His wife had opened one HSBC account on 15 July 2000.Between 21 June and 25 July 2000, numerous deposits were made into these accounts. Between 21 June and 30 June 2000, there were nine cash deposits (totalling 1 786 285.50 HKD) made into the defendant's HSB account by or on behalf of his brother. On or about 5 July 2000, the defendant drew a cheque on his HSB account in the sum of 1 780 000.00 HKD, which was paid into a joint account held by his elder brother and his girlfriend. Between 14 and 25 July 2000, there were 11 cash deposits (totalling approximately 80 000.00 USD) made into the defendant's HSBC foreign currency account. Between 15 and 24 July 2000, there were eight cash deposits (totalling approximately 40 000.00 USD) made into his wife's newly opened HSBC account. That sum of 40 000 USD was transferred to the defendant's account on 26 July 2000. A sum of 122 000 USD in that account was put 'on time deposit' for one month. On 20 September 2000, the defendant transferred 120 000 USD from his HSBC Forex account to an account in the name of his brother's girlfriend at the same bank. The defendant denied any involvement in illegal activities. Upon questioning, the defendant denied knowledge regarding the fake passports. He also declared that the money in his (the defendant's) bank account was for margin trading in foreign exchange for a friend. The defendant believed his brother to be engaged in migrant smuggling activities and would have told him not to keep the passports in his flat. The defendant indicated that he had received from his brother, by express mail from overseas, 10‑20 airline tickets, which he saved for him. The defendant declared that, following a conversation with his brother, he suspected the latter to be involved with the deaths (in June 2000) of 58 irregular migrants, who had died in a container in Dover, in England, one reason being that they all came from a place near his home town in China. In addition, the defendant stated that his brother had asked him to transfer the money paid into his accounts to that of his brother's girlfriend. Accordingly, the defendant inferred his brother must have obtained that money by illegal means because his brother had told him that "there was a lot of money to be made by arranging for people 'to go to other places'". DECISION AND REASONING The defendant was convicted of dealing with property known or believed to represent the proceeds of an indictable offence (migrant smuggling). This decision was upheld on appeal. The Court deemed unrealistic the Defence's submission according to which there would be insufficient evidence to ground a conviction. This was so in view of the compelling evidence before the Court re (i) cash deposits in June and July 2000; (ii) money transfers; (iii) location of the passports, (iv) defendant's declarations to the police. Likewise, the High Court agreed with the Prosecution's argument that the defendant's use of his brother's very substantial sums of cash between June and September 2000 - given his knowledge of the brother's limited resources and what his brother had told him re financial opportunities deriving from 'helping people to go other places' - pointed directly to a link between thepassports, migrant smuggling and money laundering. Importantly, regarding the money laundering charges, the Court emphasized there is no needto prove the specific conduct of the underlying offence (in this case, migrant smuggling). Rather, only the type or category of the crime need be proved. SHERLOC Case Law Database on the Smuggling of Migrants - China |