The illicit trafficking and misuse of firearms has far reaching consequences both on security and development. Module 10, Impact of Firearms on Society and Development, is entirely dedicated to this topic.

One of the most obvious and tangible consequences of the misuse of firearms is the amount of gun-related injuries and deaths, but the impact of firearms goes much beyond this initial consequence. 'Armed violence' is the term widely used in this context and refers broadly to "the use or threatened use of weapons to inflict death, injury or psychosocial harm" (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2009: 13; 2011: ii). Armed violence is not limited to the use of firearms, but to any weapon. It emerged in the 1990s in the context of international efforts aimed at reducing the human suffering associated with the use of arms. This has been the constant Leitmotif of the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, a diplomatic initiative launched in 2006 and endorsed since by over hundred countries, aimed at addressing the interrelations between armed violence and development (Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2006).

When the issue of armed violence emerged, available data was at best ad-hoc and in many cases inaccurate and misleading. Today, besides the Geneva Declaration Secretariat, other international and regional organizations, including the UNODC ( Statistics and Data Portal) and the World Health Organization (WHO), regularly collect data on homicides and violent deaths, contributing to the global understanding of trends and patterns in armed violence.

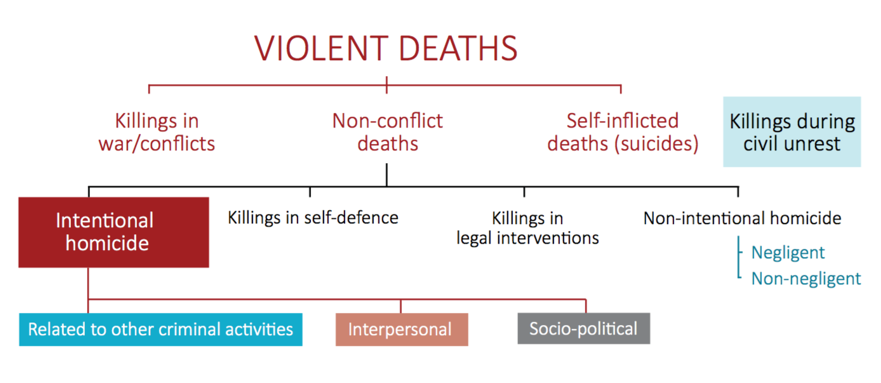

The standard approach to measuring the impact of armed violence is through its most common proxy of 'violent deaths' , which separates out conflict deaths, non-conflict deaths and suicides or self-inflicted deaths. For example, the violence in Syria and Yemen led to an increase in conflict deaths. On the other hand, non-conflict deaths would include all forms of intentional and non-intentional homicide. The Global Study on Homicide 2013 by UNODC (Dawson-Faber, 2014) used the following typology.

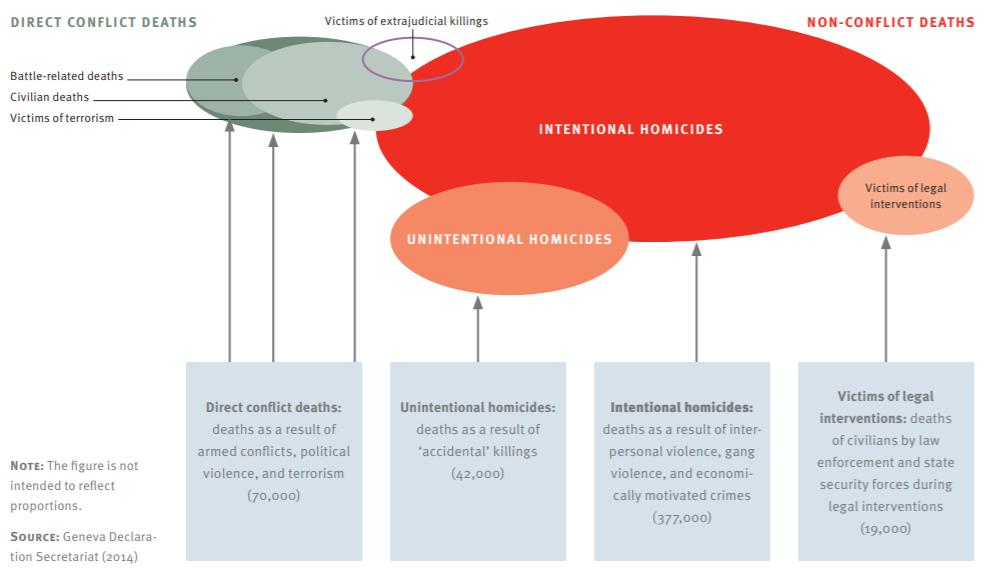

A different approach has been followed by the Geneva Declaration Secretariat (2011) in its second edition of "The Global Burden of Armed Violence", which moved away from the classical distinction between 'conflict' and 'non-conflict' violence and proposed a unified means of recording and reporting armed violence. This approach takes various interrelationships between diverse levels of lethal violence into account, and the way they are accounted for. It has remained the basis for measuring violence by the Geneva Declaration Secretariat in its subsequent editions.

The underlying assumption of this 'unified ' approach is that it is virtually impossible to classify contemporary violence in mutually exclusive categories due to the blurred lines between political, interpersonal, criminal, and organized violence. Deaths may be recorded under different categories - or not at all - depending on the national context (McEvoy and Hideg, 2017).

No matter how represented and accounted for, a common finding of predominant research into armed violence points to the fact that the vast majority of the killings worldwide are produced outside of armed conflict settings.

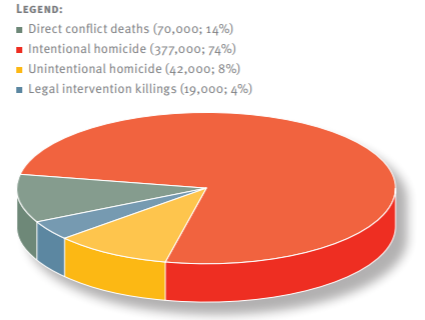

In its 2015 edition, the Geneva Declaration revealed that 74% of the recorded intentional homicides were attributable to interpersonal violence, gang violence, and economically motivated crimes (377,000). Direct conflict deaths (70,000) accounted for 14%, an increase on previous years largely due to armed conflict in Libya and Syria. For the period 2007-12, the average global rate of violent deaths stood at 7.4 persons killed per 100,000 of population (Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2015).

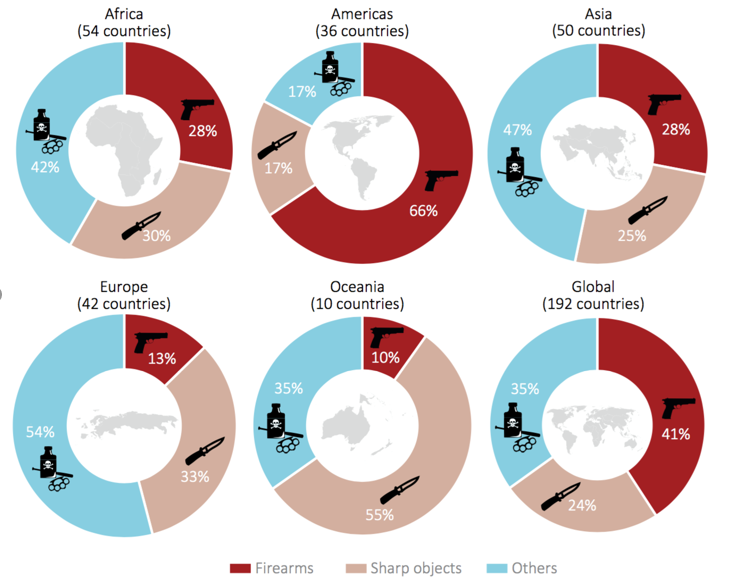

According to this study, firearms represent a constant element responsible for a large majority of the violent deaths, with major differences across world regions (firearms were used in 46.3 per cent of all homicides and in an estimated 32.3 per cent of direct conflict deaths. This accounted for an average of 44.1 per cent of all violent deaths, or an annual average of nearly 197,000 deaths for the period 2007-12) (Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2015). Similar findings have also emerged from the UNODC Global Homicide Study (see below).

Firearms are present in any type of armed conflict regardless of its geographical location. The use of firearms/SALW in conflicts was documented as early as 1997 in the report of the United Nations Small Arms Panel, which also proposed the first definition of SALW (see the definitions in this Module). A cursory look at the arms being used in contemporary conflicts reveals the same findings. A 2015 report on weapons used by ISIS illustrates the geographical and technical variability of firearms used in conflicts (Sputnik News, 2015).

The presence of firearms, especially military-grade weapons (for further explanation see Module 2) in a conflict zone has a significant impact on the conflict. First, it leads to an increase in lethal and destructive outcomes, and overall costs of the conflict. Many local conflicts use basic weapons like single-shot rifles, but as more sophisticated and powerful weapons are sent to the conflicts, there are several consequences: casualties increase; medical costs increase; development programmes are affected; and once the parties to the conflict are better armed, they are less likely to negotiate a ceasefire, emboldened by more lethal weapons under their control. Second, there is generally an increase of criminal acts in the conflict area. Armed robberies, domestic violence, hijacking and kidnappings, terrorism, slavery, trafficking of humans and goods, endangered species poaching, stealing of livestock - all tend to increase as more firearms become available in conflict areas. Once proliferated, firearms are much harder to get under control, even when peace is negotiated, and criminal acts continue even after the conflict has ceased (Laurance and Meek, 1996).

It is not only arms availability that creates these effects; the root causes of human suffering seen in these conflicts is more complex, but the role of firearms should not be ignored. In its September 1997 report the United Nations Small Arms Panel of Experts stated that:

"accumulations of small arms and light weapons by themselves do not cause the conflicts in which they are used [...]. These conflicts have underlying causes which arise from a number of accumulated and complex political, commercial, socio-economic, ethnic, cultural and ideological factors. Such conflicts will not be finally resolved without addressing the root causes." (United Nations General Assembly, 1997: 10).

The remainder of the United Nations Small Arms Panel report, and a host of other places in the international community, focus on the actual tools of violence, which bring meaning to the adjectives "deadly" and "mass" being used to define conflict.

While there is considerable debate as to the causal role that firearms play in explaining armed violence, there is little doubt that the access to, and the availability of, firearms in the hands of criminal or terrorist groups, local gangs, or politically motivated groups are driving factors in the exacerbation of violence. Many say that it is the local culture and context that determine the damage from firearms. Peter Squires (2014) puts it another way:

"Arms researchers and NGO development workers and project evaluators in different countries on different continents are often quick to point out the importance of local cultures, histories, resources, circumstances, politics, factions and disputes that different one chronic and hyper-violent conflict complex from another….whatever the reason for the poverty, state failure, corruption or compromised governance suffered by any region, the arrival and dispersal of tens of thousands of assault rifles is pretty much guaranteed to trample all over local specificities and change things….The key point is that, whatever was unique or different about a region prior to its weaponization is now likely to be less important than the fact that the area is awash with, for example, AK-47s. "

The distinction in conflict and non-conflict violence is typical of the development perspective, as reflected in large part of the dominant research in this field. However, from a crime prevention and criminal justice perspective, most forms of armed violence generated in a non-conflict situation refer in fact to acts of crime. The most often used indicators to track trends in crime-related armed violence are the homicide rate, measured in number of homicides per 100,000, and the number of people killed with a firearm; standard indicators used in developing and developed countries.

Reducing the number of homicides is also one of the most common measurable outcome variables in many armed violence reduction programs or policies of international organizations or government agencies aiming to reduce the levels of violence. The reason for this is obvious: the moral aspect of killing with homicide being seen in majority of societies as the most severe crime that can affect that society. But the count of humans dying also has broader implications: the number of deaths from firearms, if increasing, would indicate greater fear in the regions where these are occurring. It could also indicate more revenge killings, an increase in domestic violence, and a decrease in ordinary citizens ' willingness to participate in programs designed to lower the killings. Further on in this Module, some of these aspects will be discussed. But the first key message from this Module is that violent deaths, especially intentional homicides with firearms, are a valid proxy indicator for other negative effects that are rather difficult to quantify; for example, local and regional security, social implications, and local impact on politics or economy.

In its 2013 Global Study on Homicide, the UNODC disaggregated homicide data by weapon used (firearm, knife, other) and by region. In line with other research findings quoted above, the UN study revealed that globally 41% of homicides were committed with firearms. The regional disaggregation indicated that the highest level of death by a firearm occurred in the American region (66%), with the lowest levels in Oceania (11%) and Europe (13%).

As McEvoy and Hideg (2017: 49) note, firearms play a significant role in the commission of homicides: "Globally, firearms were used in 44 per cent of all homicides in 2016. In 2004, they were used in about 40 per cent of all homicides. Available data suggests that global fatalities from firearms rose from about 171,000 in 2004 to 210,000 in 2016. "

This increase is in line with wider trends in total homicide rates, which grew from 5.11 to 5.15 per 100,000 of the population in 2015-16. Reviewing where these events are taking place, the authors suggest that firearms-related deaths often happen in conflict regions, with 41% firearms deaths occurring in conflict zones. However, when looking at all firearms fatalities across the world, the clear majority of the fatalities are not conflict deaths, with over 80% being non-conflict intentional homicides. Conflict deaths account for a further 15% and because of a legal intervention, non-intentional homicides a further 4%. Hence, even in conflict zones, many firearms related deaths are not directly related to conflict.

The direct costs associated with fatalities and injuries are manifold. At the macro-level, there are financial costs to the State, such as health and social care costs, the costs to the criminal justice and penal systems, and the economic impact of lost productivity. Furthermore, the perception that a country or region is unsafe because of armed violence also has a significant impact on investments, tourism and other business sectors.

The negative impact of violence and insecurity on tourism and travel has been estimated at USD 2.7 billion in losses over the first six months of 2014 in Thailand and USD 2.5 billion from 2011 to 2013 in Egypt ( Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2015). Specific examples include the terrorist attack on the beaches of Tunisia in 2015, in which a firearm was used to murder 38 tourists. The decrease in tourism significantly affected the country 's finances in the aftermath of the attack due to the significant percentage contribution of this industry to the GDP of the country. Accordingly, there was a reduction in economic growth for the country from 3% to 0.5% that year (Kim, 2015). The costs following the Paris attacks in 2015 in which 130 people lost their lives, most of whom were killed by firearms, was measured not only in terms of the impact on the tourist industry, but also in terms of the increased investment in security, as well as the health and social care costs ( Walker, 2015).

At the meso-level, there are costs to communities, both in terms of financial costs, and the impact on feelings of safety and security, and costs to other organizations such as insurance companies. In the case of the terrorist attacks noted above, there were also costs to local businesses including restaurants and hotels. Many businesses were forced to close due to the loss of income following these events.

McCollister et al. (2010: 1) outline the costs of violent crime in the US, estimating an overall financial cost of $194 billion:

"Crime generates substantial costs to society at individual, community, and national levels. In the United States, more than 23 million criminal offenses were committed in 2007, resulting in approximately $15 billion in economic losses to the victims and $179 billion in government expenditures on police protection, judicial and legal activities, and corrections. Programs that directly or indirectly prevent crime can therefore generate substantial economic benefits by reducing crime-related costs incurred by victims, communities, and the criminal justice system."

Finally, at the micro-level, there is impact resulting from the personal tragedies behind each statistic: from the emotional and financial impact on bereaved families to the psychosocial impact for those left with life-changing injuries. One example of this is the impact that violent crime has on child witnesses. Collins and Swoveland (2014) note the emotional effects of stress experienced by children and young people from trauma arising from exposure to violence, and how their emotions may be internalized and lead to later aggression and further violence. Hence, such exposure can have lifelong effects with generational consequences and so a long-term approach to dealing with these issues is therefore paramount.

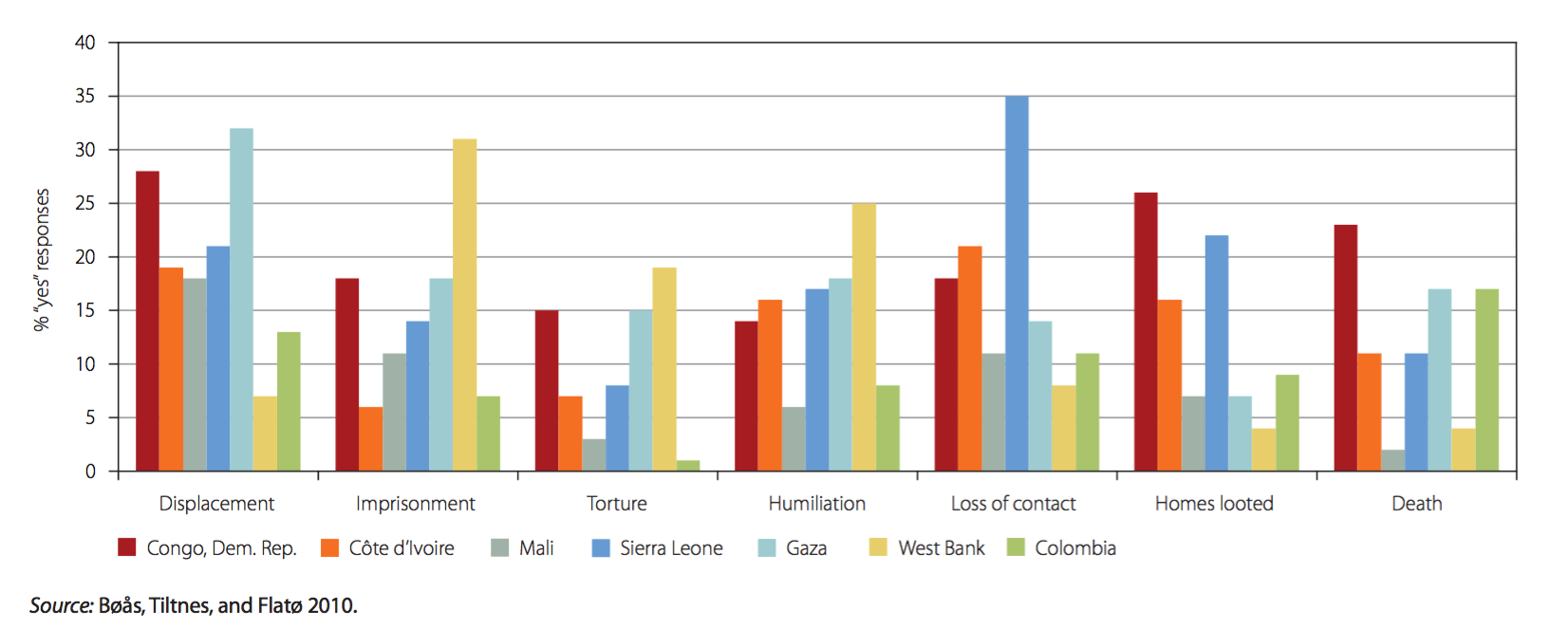

In 2011, the World Bank 's Annual World Development Report entitled ' Conflict, Security and Development ' addressed the human costs of the violence brought about in most cases by the widespread proliferation of weapons or 'weaponization' of societies, in or recovering from conflict. The authors note the effects of violence on human security and dignity, and freedom from violence and fear is a basic human right (The World Bank, 2011). To provide empirical evidence of the human costs, the study conducted a survey of people in seven conflict areas- Democratic Republic of Congo, Cote D'Ivoire, Mali, Sierra Leone, Gaza, West Bank and Colombia.

This study emphasizes the pain and suffering caused by violence and insecurity as well as negative impact on people 's behavior and economic activities. In conflict situations, the destruction of physical capital and infrastructure - roads, buildings, clinics, schools - and loss of human capital through displacement and migration, represent serious development costs. Even in non-conflict settings where criminal or interpersonal violence does not cause widespread physical destruction, it is important not to understate the threat to State capacity, the business environment, and social development posed by chronically high levels of violence, organized crime, and the corruption that often follows it ( Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2015).