In September 2006, the United Nations adopted the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy. In the resolution that adopted the strategy, the United Nations Member States resolved to “consistently, unequivocally and strongly condemn terrorism in all its forms and manifestations, committed by whomever, wherever and for whatever purposes, as it constitutes one of the most serious threats to international peace and security” (United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism, 2006).

Terrorism has been a national threat for many decades, but the 9/11 attacks of 2001 on the United States brought deeper interest and research into this topic. Although those attacks did not involve firearms, many of the more recent attacks (for example, the 2008 Mumbai hotel attack, the 2015 Port El Kantaoui attack in Tunisia, the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, and the 2017 Istanbul nightclub attack) have relied heavily, or entirely, on the use of such weapons.

It is thus of no surprise that INTERPOL (2018) identified illicit firearms trafficking as an area of concern and highlights the use of trafficked firearms by terrorist groups.

This section of the Module focuses on the use of firearms by terrorists and their links to firearms trafficking. It addresses only marginally issues around definitions of terrorism, as this is discussed in the UNODC Teaching Module Series on Counter-Terrorism. Instead, this Module’s focus is on the demand for firearms as tools for carrying out attacks by terrorist groups and as commodities for trading with other organizations.

As discussed in the UNODC Teaching Module Series on Counter-Terrorism, one of the most challenging issues associated with terrorism-related topics is the lack of a universally agreed definition of what constitutes terrorism. While, all UN Member States adopted by consensus the 2006 UN Global Counter Terrorism Strategy, it remains within the sovereign prerogative of Member States whether and how to define the term terrorism. In practice, definitions of terrorism can be found in many national legislative systems, and in academic studies, although these invariably differ and this often presents an obstacle to the way States can cooperate in the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of terrorism-related crimes.

Module 4 of the UNODC Teaching Module Series on Counter-Terrorism contains a more in-depth analysis of the complexities and implications associated with the absence of a universally agreed definition of terrorism.

For the purposes of this Module, it is noted that despite the absence of a universal definition of terrorism within the UN framework, guidance is provided by 19 UN counter-terrorism instruments, which set out the elements of specific criminal offences (for example: hijacking of aircraft; terrorist bombings; hostage-taking) deemed to constitute acts of terrorism. Moreover, article 2 of the 1999 UN Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (United Nations, 1999) provides that acts falling within those instruments annexed to the Convention, or any other acts intended to cause death or serious bodily injury to a civilian, or to any other person not taking part in the hostilities in a situation of armed conflict (when the purpose of such acts by its nature of context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a government or an international organization to do, or to abstain from doing any act), must be criminalized by States parties for terrorist financing purposes. However, none of these 19 instruments address specifically acts of terrorism committed with firearms/SALWs.

It is interesting, however, that the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) explicitly refers in its preambular paragraph 6 to the possibility of applying UNTOC to the fight against terrorism by calling upon States “to recognize the links between transnational organized criminal activities and acts of terrorism, taking into account the relevant General Assembly resolutions, and to apply the (…) Convention in combating all forms of criminal activity as provided therein” (UNODC, 2004: 3).

Under UNSCR 1267 and successor resolutions, the UN Security Council has designated certain individuals and groups associated with Al Qaida, elements of the Taliban (deemed to pose a threat to the peace and security of Afghanistan), Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or Da’esh), and Al Nusrah Front, as subject to arms and travel embargos and financial (asset-freezing) sanctions imposed by the Security Council. These must (by virtue of Chapter VII of the UN Charter) be enforced by all UN Member States.

What is apparent, however, is that despite these legislative attempts to pin down definitions, the absence of clarity in the differences between the terms ‘terrorism/terrorist groups’ and ‘organized crime/organized criminal groups’ is further complicated by the fact that there is often synergy in the tactics used and the targets chosen by both. For example, the use of force for political purpose is a recurring theme in academic definitions of terrorism, but also underpins the modus operandi of OCGs. The assassination of Italian MP Pio La Torre in 1982 by the Sicilian Mafia, and of Colombian Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla in 1984 by the Medellín drug cartel, illustrate this point; both were politically motivated, but neither were considered acts of terrorism, nor were the perpetrators regarded as a terrorist group.

Differences do become clearer in the demand and access to firearms, particularly at the level of terrorist organizations/groups. While lone wolf terrorists usually access firearms for individual attacks, either through legal or illegal means, terrorist cells and groups usually access them through illicit means. Terrorist groups (terrorist organizations, insurgents, and armed groups) generally access firearms through large-scale trafficking operations, or in some cases through illicit productions. This Module will consider these issues in more detail in the next section.

The fact that terrorist groups use firearms is indisputable. Recent events have shown, however, that groups are not wholly reliant of these types of weapons, and are sufficiently adaptable to take advantage of items which are less well-regulated and easily available. The increasing number of attacks using vehicles against pedestrians (for example: Manhattan, US; Barcelona, Spain; London, UK; Stockholm, Sweden; Nice, France) or the use of self-manufactured explosive materials (Boston, US; Colombo, Sri Lanka; Mumbai, India) are examples of this turn. Although such adaptability and flexibility must be borne in mind, this section will focus on the demand that terrorist groups have specifically for firearms.

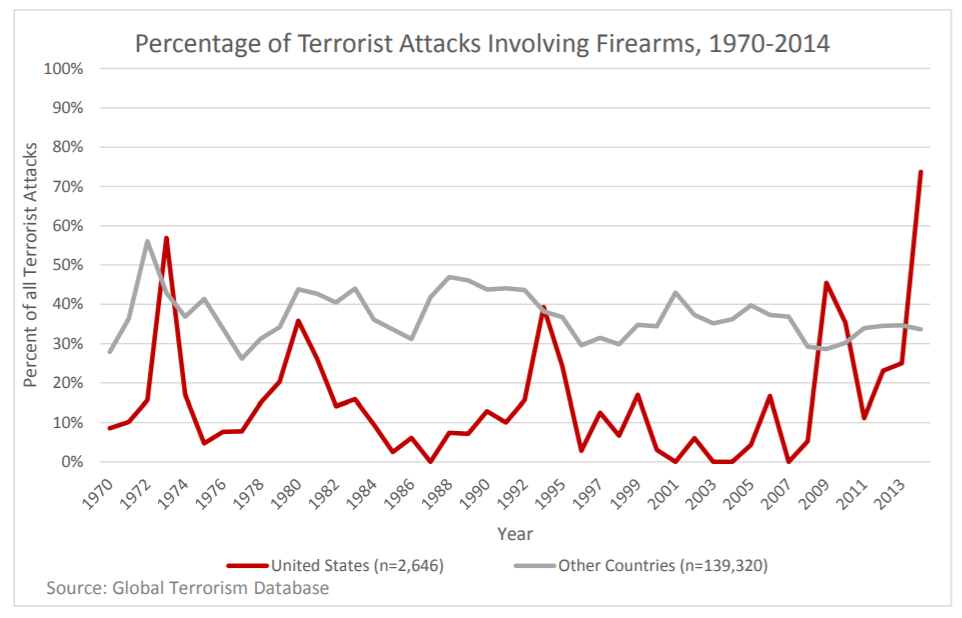

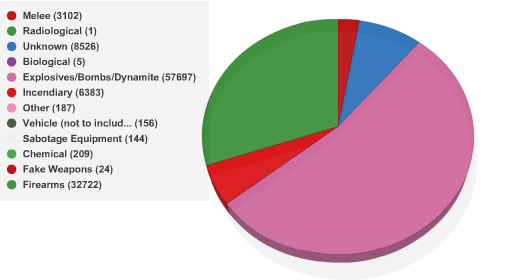

Terrorist groups predominantly use firearms for defensive or offensive reasons. Most of the literature does not support the idea that terrorist groups are involved in selling weapons to other groups; rather that they are net purchasers of weapons, often from OCGs (as elaborated in Section 5 of this Module). Tessler et al. (2017) report that in the States forming the focus of their study (mainly US, Canada, European countries, Australia and New Zealand), firearms were the third most frequently used method of attack (behind explosives and incendiary devices). However, they go on to note that “Although firearms were used in fewer than 10% of terrorist attacks between 2002 and 2016 in the examined ‘Western’ countries, they accounted for about 55% of the fatalities” (Tessler et al., 2017: E3). An earlier longer-term study by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START, 2015) showed a similar pattern of firearms use – generally below 50%, but with higher lethal consequences.

Feltes (2016: Section 3) focused specifically on al Qaeda affiliated or inspired groups reporting how “simple IED technologies and firearms seem to be the weapons of choice for these groups.”

The largest demand for firearms comes from terrorist groups focused on territorial and political control. Al Qaeda, ISIS/Daesh, Boko Haram, Ansar al-Sharia or Abu Sayyaf are just some examples of terrorist groups that require large supplies of firearms and ammunition so that they can gain and maintain control over territories. In addition, multiple insurgency groups are classed as terrorist groups at national or international level who add to the list of high demanders of illicit firearms. Unlike OCGs who deal in small quantities, the terrorists’ demand for weapons is specialized, covering a broad spectrum of arms and ammunition. It is this demand that is actually fuelling large-scale firearms trafficking.

Evidence collected by Conflict Armament Research (2014) showed that the Islamic State uses firearms and ammunition manufactured in at least 21 different countries, including China, Russia and the United States. It is obvious that transferring this large amount of firearms and ammunition is only achievable with elaborate trafficking schemes using facilitators and secure routes, strengthening the presumption that large terrorist groups source weapons through large-scale trafficking.

An alternative is the manufacturing of firearms using workshops under the control of the terrorist or insurgent groups. From Asia to America, manufacturing is a source of firearms, but only complementary to trafficking since artisanal manufacturing is unable to meet the demand in number and quality.

Nesser and Stenersen(2014)identified 17 terrorist plots with firearms in Europe between 1994 and 2013 (the majority influenced by al Qaeda), and the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) lists firearms as second most popular weapon of the worldwide network of al Qaeda – with 692 attacks and plots out of a total number of 1909 incidents affiliated with al Qaeda globally (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2018).

As can be seen in Figure 7.7, firearms represent one of the main methods of perpetration of terrorist attacks. Regardless of whether attacks are by lone wolves or terrorist cells, the use of firearms guarantees a large, controlled number of victims.

Terrorist groups use firearms to facilitate a main attack. For example, during the Berlin Christmas Market Massacre, the attacker seized a truck after using a pistol to shoot and kill the driver. He then rammed the stolen truck into the crowded Christmas market killing 12 people and wounding 49 others.

Kidnappings, trafficking in drugs, wildlife and cultural goods, attacks against financial or legal institutions, and attacks against personnel from military, governmental or international organizations are just some examples in which terrorists use firearms to commit or facilitate offences. Since large numbers of firearms are not needed to facilitate or carry out an attack, they can be procured from small-scale trafficking, artisanal manufacture and modification or reactivation.

Most of the literature does not support the idea that terrorist groups are involved in selling weapons to other groups, rather than they are net purchasers of weapons, often from OCGs – discussed in Section 5 of this Module.

A particular situation encountered, especially in post conflict Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) processes, is where cash for guns or buyback programmes tend to give a lucrative value to the firearms in possession of former combatants, being them insurgents or members of designated terrorist groups. It was argued that buyback programmes are encouraging small-scale trafficking and other associated crimes in the race of procuring more firearms to be later surrendered for cash. Corroborated with some noticeable failures in achieving the expected results, the buyback programmes as a good practice became a subject of debates, while other incentives, like education, development support or food are recommended to replace cash in DDR. (The New Humanitarian, 2011)

In Nigeria and its Northern neighbours, Boko Haram (sometimes referred to as the Islamic State in West Africa), has been operating since 2002, although an upsurge in activity started in 2009. Onuoha (2013: 6) reports that “hundreds of weapons including RPGs, rocket launchers, anti-aircraft missiles, and AK 47 rifles have been intercepted by security operatives in various locations in north-eastern Nigeria. It is widely believed that these weapons found their way to Nigeria from Libya and Mali.”

In addition, Boko Haram may also source some of its weapons from Chad and from sympathetic members of the Nigerian army (Windrem, 2014). Whereas with the “ant trade” the trading of weapons to and from OCGs is prevalent, seizures of weapons heading to Boko Haram reveal larger shipments to be the norm in the region. For example, “four Toyota Hilux vans, 10 AK-47 rifles and magazines, two G3 rifles and 10 x 4 40mm bombs, three RPG tubes, and 85 rounds of special ammunition” were seized by members of the Multi-National Joint Task Force in one haul on 4 August 2013 (Onuoha, 2013: 7).

UNODC (2011) points out that while the era of major civil wars in Africa has largely abated, reducing the demand for firearms/SALW, the firearms trafficked over that period continue to be re-circulated throughout the region, providing another potential source of weapons for Boko Haram.

Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) is a terrorist organization which primarily operates in Peru. Although the group is not as powerful as it once was, it has been operating in Peru since the 1980s. According to the Andean Air Mail and Peruvian Times (2018), it is possible that offshoots of Sendero Luminoso have evolved to become protectors of cocaine trafficking routes and the cross-border shipment of cocaine into Bolivia. Theidon (2013) notes that one of the weapons of choice of Sendero Luminoso was the tiracha, or homemade gun, which poses law enforcement problems different to that of manufactured firearms being trafficked into the country.

The Spanish Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC – Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) is the largest of Colombia’s rebel groups and according to Encyclopaedia Brittanica is estimated to have some 10,000 armed soldiers and thousands of supporters largely drawn from Colombia’s rural areas. “The general trend appears to be for guerrillas to purchase their weapons in small quantities, most of which are of the military-grade,7.62-caliber variety…..There have been signs, however, of a possible shift in FARC’s purchasing patterns toward “bulk buying” (Cragin and Hoffman, 2003: xv). In addition to firearms trafficking, FARC was sourcing weapons from its own production in illegal factories in Colombia or abroad (UNODC, 2006).

In Colombia, terrorist groups and organized criminal groups cooperate closely to control the illicit drugs business and engage in firearms trafficking. In April 2018, Colombia’s Prosecutor General declared that former FARC combatant and leader of the dissident group, Walter Arizala, alias “Guacho”,has close ties to the Mexican drug cartel Sinaloa, whose members have an established presence in Southern Colombia, and is thought to be in charge of controlling the south eastern drug route from Colombia (Fitzpatrick, 2018). In October 2018, Ecuadorian authorities started an investigation on the theft of weapons from military stocks and their possible sale by members of the army to “El Guacho” in Colombia (Antolinez, 2018).

Links between Italian ‘Ndrangheta members and ISIS groups involve the trafficking and illicit procurement of firearms as well as that of cultural goods. The Italian Mafia is thought to sell rifles and other forms of weapons to IS leaders in Libya in return for looted archaeological treasures and artefacts. According to Italian newspaper La Stampa, “After getting them from Libya, the suspected ‘Ndrangheta gangsters sell on the priceless artefacts to Russian and Asian collectors” (Quirico, 2016: 1). The article further states that the same Calabrian network, which dominates Europe’s drug trade, works with the Camorra in Naples to buy Kalashnikov type rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers smuggled out of Ukraine and Moldova by the Russian Mafia.

The weapons used in the 2015 attacks on the Charlie Hebdo magazine headquarters and Jewish supermarket in Paris have subsequently been shown to have been purchased legally in Slovakia as “deactivated” movie props. Deactivation involves the modification of a working firearm to prevent it being fired, and deactivated weapons can be then sold for use as film and theatre production props, or to private collectors, in many European countries with far fewer restrictions than working guns.

In the 2015 Jewish supermarket attack, the German magazine Der Spiegel reported the death of Yohan Cohen, a 20-year old student working in the supermarket, at the hands of terrorist Amedy Coulibaly, who had been radicalized in prison. Coulibaly “was carrying two Ceska Sa vz.58 automatic rifles. One of them was a short version, which had once been modified so that it could only fire blanks – transformed into a harmless noise-maker. But it had since been converted back into a lethal weapon. It was this Ceska that Coulibaly used to shoot Cohen – deadly shots from a weapon that should not have been available on the open market any longer” (Candea et al., 2016: 1).

The report of Project SAFTE (2018: 201-211) lists the tracing results of the firearms used in these attacks, and it is interesting to note that despite tracing requests being made for all fourteen firearms, only five were successful (the two vz.58 rifles and three of the six Tokarev TT33 pistols). This underlines the importance of accurate record keeping on arms transfers, as discussed in Module 3 (Legal Arms Market) and Module 6 (National Regulations on Firearms).

The UNODC Study on Firearms has identified deactivated weapons as posing particular challenges for law enforcement, and attraction to criminals and terrorists “because of the considerable profit to be made and a lack of the common EU rules (which facilitate the criminal activities)” (UNODC, 2015: 43).

As these examples have demonstrated, terrorist groups can obtain small arms and light weapons (SALW) using a range of methods and routes, ranging from legal purchase (and then illegal reactivation) of deactivated weapons, to bespoke weapons manufacture or recycling of weapons left over from previous conflicts.

The next section will discuss the links between organized criminal groups and terrorist groups in the illicit weapons trade.