The Protocol against Trafficking in Persons provides a non-exhaustive list of what falls within the scope of the term "exploitation". Article 3(a) of the Protocol provides that "[e]xploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs". The lack of an agreed definition of exploitation can lead to a degree of interpretative discretion and, as a consequence, to inconsistency in national implementation. As a result, questions remain about certain aspects of the definition of exploitation and its practical application.

Note that this element of the offence requires proof that the offender acted with the purpose of exploiting the victim. It is unnecessary for the victim to have been exploited, as long as this was the offender's purpose.

When the Protocol was negotiated, there was a high level of agreement around a core set of practices to be included as forms of exploitation, such as sexual exploitation and forced labour. However, some forms proposed for inclusion were rejected, either because they were seen as already being encompassed within another form of exploitation to be listed, or because they were felt to fall outside the scope of the Protocol. For example, the term "labour exploitation" was proposed but not accepted and proposals to explicitly include a profit or benefit element to the concept of exploitation were also rejected during negotiations ( UNODC, 2015).

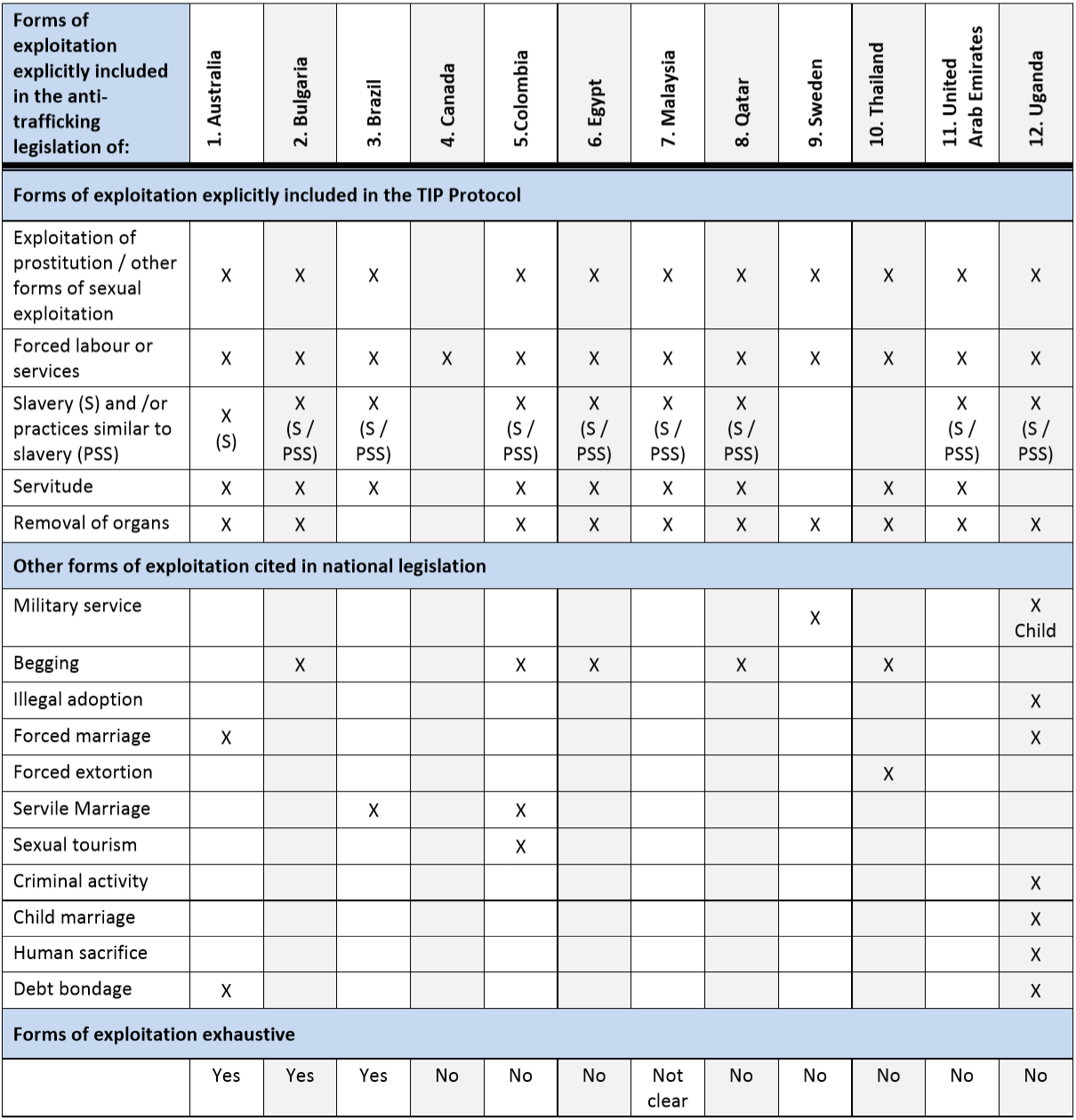

National legislation and case law is bringing some clarity and may add other forms of exploitation. The list of exploitative purposes set out in the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons is not exhaustive and may be expanded. The non-exhaustive character of the Protocol's definition is manifested in two ways: (i) through the phrase "at a minimum"; and (ii) through the inclusion of examples of exploitation that are not otherwise defined in international law. States are permitted to expand that list by either adding new concepts or by interpreting undefined concepts in a way that captures certain conduct relevant in a given country or cultural context (see examples in Box 10 below).

In terms of expansion, however, there are some limits, which may potentially include a threshold of seriousness that operates to prevent the expansion of the concept of trafficking to less grave forms of exploitation such as labour law infractions. It should be noted, however, that the Protocol does not clearly establish any such threshold ( UNODC, 2015).

The existing international legal definitions of slavery and forced labour are directly relevant to interpreting their substantive content within the context of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons:

The Travaux Préparatoires provide three Interpretative Notes relevant to the concept of exploitation: forms of sexual exploitation other than in the context of trafficking in persons are not covered by the Protocol; the removal of a child's organs for legitimate medical or therapeutic reasons cannot form an element of trafficking if a parent or guardian has validly consented; and references to slavery and similar practices may include illegal adoption in some circumstances.

Sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism is another form of exploitation. It is a phenomenon whereby a person travels abroad with the intention of engaging in sexual activity with children.

Steps have been taken both internationally and domestically to criminalize tourists travelling abroad with the intention of engaging in sex with children in countries in which children are vulnerable to sexual exploitation and legal protections are weak. Such steps include: (a) multilateral, regional and bilateral cooperation between law enforcement agencies in the country of residence of offenders and the destination country in which the offending takes place; and (b) countries criminalizing child sex offences committed by their citizens abroad, rather than relying on the destination country to arrest and prosecute them.

Article 10 of Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography provides:

An example of a national law against sex tourism is the US Prosecutorial Remedies and Other Tools to End the Exploitation of Children Today Act of 2003 (PROTECT Act).

In United States v Seljan, John W Seljan, an 85 year old retired businessman was arrested in Los Angeles airport on his way to the Philippines to have sex with two girls, ages 9 and 12. Seljan was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

According to the World Economic Forum in its 2018 publication Child sex tourism and exploitation are on the rise - Companies can help fight it , sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism is increasing worldwide. However, its rise has been particularly high in Latin American countries. One of the main reasons for this rise appears to be the countries' relatively uncomplicated and cheap accessibility to sex. Child poverty is also a contributing factor. Note that the counter-trafficking sector has shifted away from using the term "sex tourism" (see CNN Freedom Project, 31 August 2018) .

In some forms, pornography constitutes a form of exploitation within the definition of trafficking in persons. Child pornography is one example. It is defined in article 2(c) of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography as "any representation, by whatever means, of a child engaged in real or simulated explicit sexual activities or any representation of the sexual parts of a child for primarily sexual purposes". Article 3 further provides:

Each State Party shall ensure that, as a minimum, the following acts and activities are fully covered under its criminal or penal law, whether such offences are committed domestically or transnationally or on an individual or organized basis:

(…) (c) Producing, distributing, disseminating, importing, exporting, offering, selling or possessing for the above purposes child pornography as defined in Article 2.

The counter-trafficking sector has shifted away from the use of the term "child pornography" on the basis that it trivializes the issue, stigmatizes victims and makes it difficult to raise awareness or facilitate enlightened discourse. The sector thus rather refers to "child sexual abuse" and "child sexual abuse material". See Ecpat International, Advocacy and Campaigns (2016) and Interagency Working Group in Luxemburg, Terminology Guidelines for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (2016).

Other examples include violent, abusive and coercive forms of pornography. By way of example, see Box 15.

Linda Boreman, aka "Linda Lovelace"

Linda began her booming career in the porn industry in 1972 due to the coercion of her husband. She starred in one of the most popular pornographic films of the era, but it was later revealed that she was forced into appearing in this production. Later in life, Linda became an advocate for the anti-porn movement, sharing her story around the world. In the following quote, she shares the first time she participated in a pornographic shoot:

"My initiation…was a gang rape by five men… It was the turning point in my life. He threatened to shoot me with the pistol if I didn't go through with it. I had never experienced anal sex before and it ripped me apart. They treated me like an inflatable plastic doll, picking me up and moving me here and there. They spread my legs this way and that, shoving their things at me and into me, they were playing musical chairs with parts of my body. I have never been so frightened and disgraced and humiliated in my life. I felt like garbage. I engaged in sex acts for pornography against my will to avoid being killed. The lives of my family were threatened."

Removal of human organs is explicitly mentioned as an exploitative purpose in article 3 of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons. Unlike the other exploitative purposes listed in article 3 of the Protocol (slavery, servitude and sexual exploitation) the removal of organs does not constitute a practice that may be considered inherently exploitative.

The World Health Organization ( WHO) has developed guidelines that provide the main principles applicable to human cells, tissues and organ transplantation:

Boxes 17 and 18 below illustrate two cases of trafficking for organ removal and its impact on victims' mental and physical health.

"I lived in the same district as Mr. B, who was well aware that I struggled to feed my family. Mr. B approached me and told me I could donate a kidney for 1200 Euros. He also promised me two 'bigah' land in Chitwan. He said that extracting one kidney would not make a difference to my health. I believed him and in June 2010 we made a long journey to a neighbouring country. We went directly to a hospital where I was admitted and kept for 15 days undergoing medical check-ups. On the final day of my stay they removed one of my kidneys and I was immediately sent back to Nepal. I had no idea that having a kidney extracted in such a manner is a serious crime. After my return my health quickly deteriorated. I could not work and I was physically as well as mentally weak. Everything Mr. B had promised me was not provided apart from a very small sum of money. In April 2014, I came into contact with the Forum for Protection of People's Rights (PPR) and was provided with counselling and treatment support by PPR Nepal. After few legal counselling sessions by PPR's lawyer in my district, a First Incident Report was registered against Mr. B in accordance with the Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act 2007 which lead to a trial in the district court. In June 2014 the district court ruled that Mr. B should be imprisoned for three years."

The defendant met a person named Yehia who coerced him to sell his kidney for 1500 dollars. The defendant travelled to Iraq with Yehia, who confiscated the defendant's passport upon arrival, gave it to a man named Talal, and received 500 dollars in return. Talal then took the defendant to Al-Khayyal Hospital in Baghdad and performed a surgery to remove his left kidney. Once the defendant returned to Jordan, he found 500 dollars in his bank account.Later, Yehia met with the defendant and asked him to accompany two men to Iraq to sell their kidneys. The defendant accompanied the two men to Iraq, took them to Talal, and received 300 dollars in return. While the defendant was in Iraq, the 300 dollars was stolen. The defendant was forced to return to Jordan without money and had to leave his passport in Iraq. At a later date, the defendant falsely notified the Security Centre that his passport was lost. As a result, he was referred to the Anti-Corruption Directorate and was prosecuted.The acts he committed, including selling his kidney and convincing three persons to sell their kidneys for 1300 dollars, are prohibited in Articles 10 and 4/c of the Jordanian Law on the Utilization of Human Organs. In addition, leaving his passport with the driver is prohibited under Article 18/b of the Passports Law.The Court sentenced the defendant to one year in prison for each act committed under Articles 10 and 4/c of the Law on the Utilization of Human Organs. The defendant was also sentenced to 6 months in prison for violating Article 18/b of the Passports Law.

Domestic servitude is a class of labour that can be readily exploited, increasing the risk of people working in this sector becoming victims of trafficking. Domestic labour is often undervalued and invisible and it is mainly carried out by women and girls. Domestic workers are often migrants or members of disadvantaged communities, who can be particularly vulnerable to discrimination in respect of conditions of employment. In many jurisdictions, domestic workers do not have the status and are not treated in the same manner as ordinary employees in other employment sectors. The ILO adopted the Convention 189 - Domestic Workers Convention to address this situation. It is based on the premise that domestic work should be afforded the same protection as any other form of labour. The Convention provides for a bill of ten rights for domestic workers, as follows.

Two cases of trafficking for the purpose of domestic servitude are illustrated in Boxes 20 and 21 below.

Ms Cinthia Vargas recruited the victim, a minor of 12 years old, promising to bring her to Argentina to study. After transferring her illegally, without documentation, and passing her off as her daughter, the defendant exploited her, forcing her to do domestic work, treating her poorly and not paying her agreed wages. The victim had apparently lived in Bolivia with her mother and seven siblings when her mother gave her permission to go to Argentina with Ms Vargas (defendant) and her husband Fermin (defendant). The couple had two children, aged 1 and 5 years old, and the defendants required the victim to take care of them. Ms Vargas worked in a grocery store, and required the victim to take the kids to school, wash their clothes by hand, cook and clean. Fermin did things to her, hurting her, touching her.

They all lived in the same room, with five of them in the same bed. The accused treated her badly, beat her with a belt and pulled her hair. One day Fermin raped her, which prompted her to tell the neighbor, who then reported the case to the police. The victim couldn't write because she never went to school.

Ms Vargas introduced the victim to other people as her niece. According to the statement of the victim's mother, the defendants were not relatives of the victim.The Attorney General charged Ms. Vargas and Fermin as parties to the crime of Trafficking in persons of a minor (145 ter of law 26.364). Aggravating factors included the victim's intense vulnerability, the deception, violence and intimidation. The Attorney General sought 11 years imprisonment for Fermin and 10 years for Cinthia.

U.S. citizen Mabelle de la Rosa Dann recruited Peruvian victim P.C. to come to the United States as her nanny and housekeeper, promising P.C. that she would be paid $600 per month plus free room and board in exchange for working five days per week during regular business hours. But once P.C. arrived, Dann seized P.C.'s passport, and refused to pay her for two years. P.C. regularly worked from 6 a.m. until 9 p.m., and was prohibited from communicating with others or listening to Spanish language radio and television. At one point, Dann told P.C. that she owed her $13,000 and needed to work to repay the debt. Dann also asked P.C. to sign a document stating she had been paid minimum wage. This document along with P.C.'s Peruvian identification and passport were found by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in Dann's clothing drawer. At trial, Dann argued that P.C.'s testimony was tainted by her incentive to lie to obtain a T-visa and remain in the United States and that their relationship was similar to that of two female family members. The Government, in contrast, presented a case where Dann wasa woman in need of free or cheap labour, who exploited P.C. and held her in slave-like conditions. The appellate court notes that because Dann was convicted, her story has been judged as less credible by the jury. The Circuit Court discussed the forced labour conviction since Dann argued that her relationship with P.C. removed it from the forced labour statute. In doing so, the court considered the legislative history of the TVPA (2000) and noted that "legislative history suggests that Congress, in passing the act, intended to reach cases in which persons are held in a condition of servitude through nonviolent coercion." (2011 WL 2937944, *8 (C.A.9 (Cal.)) (citing the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 § 102(b)(13)). The Circuit Court also noted that "not all bad employer-employee relationships or even bad employer-immigrant nanny relationships will constitute forced labour. ... the threat of harm must be serious" and the employer must have "intended to cause the victim to believe that she would suffer serious harm - from the vantage point of the victim - if she did not continue to work." The key under section 1589, according to the court, is not just "that serious harm was threatened but that the employer intended the victim to believe that such harm would befall her." The Court considered the threats from Dann and asked whether from the perspective of P.C., these harms were sufficiently serious to compel her to remain with Dann. They answered that the threats of financial harm, reputational harm, immigration harm, and harm to Dann's children were sufficient to compel a reasonable person in P.C.'s position to remain with Dann and so Dann intended to make P.C. believe she would suffer serious harm if P.C. ceased working for Dann.

The forced enlistment or recruitment of individuals in armed conflict-related activities can also comprise a form of exploitation. Indeed, conflict may considerably increase the likelihood of exploitation of vulnerable people. For further information on the relationship between armed conflict and trafficking in persons, see Module 7.

John was taken when he was 15 years old. He was one of 700 children who were forcibly recruited by South Sudan's National Liberation Movement. "They arrested me when we were going to the garden," he told Al Jazeera. "Life in the bush was hard and if you leave, they will look for you until they find you again and they will take you back." The civil war in South Sudan is now in its fifth year. It has killed thousands and displaced millions. Monday marked International Day against the use of Child Soldiers. According to the UN, the number of children recruited in South Sudan is still rising. Sarah, who is 13, was also taken by the National Liberation Movement. "I was in the garden working and I saw these people coming and I started to run," she said. "They told me to come - why am I running? I stopped and they said to me if I run they will shoot me with the gun, and I stopped running."

Rights groups say nearly all armed groups in the world's youngest country recruited children to fight. On Thursday the National Liberation movement released more than 300 children in Yambio. Brigadier Abel Matthew of the armed group denies the children were taken against their will in the first place."They were not really forced but the conditions back then forced them and all of us together," he told Al Jazeera. Nearly 2,000 children have been demobilised in the past five years, but they are being replaced. According to UNICEF, the number of child soldiers in South Sudan has been increasing since the war began in 2013. That is despite all the warring sides repeatedly stating that they will stop recruiting children and release those already enlisted.

Many children who have been released have no idea where their families are. For others, fighting has become a way of life. "The biggest challenge is reintegration," Unicef's Mahombo Mdoe told Al Jazeera. "It's a process that takes time, two to three years for that child to go back home and resettle. We still have more kids to be released. "Our real concern is the reintegration of these children so that they don't get re-recruited again." John and Sarah say they do not want to return to the battlefield. But they also fear what lies ahead after their past experiences and wonder if they may be forced to fight again.

As they [people forced to leave their country during conflict or post-conflict situations] often leave in hurry, they take risks they would refuse to take under normal circumstances. Conflicts weaken public structures, eliminate protection initiatives and allow criminal networks to operate more freely, including across borders.

The coercion of people to undertake criminal activities can represent another form of exploitation. Forced criminality is a lucrative and low-risk enterprise for traffickers. Cases in which children are trafficked for the purpose of begging (which is an illegal activity in some countries) or pickpocketing are well known. There are examples of victims being coerced to carry out more serious crimes, for example, the manufacture and trafficking of narcotics. Victims are often forced into several types of criminal activities simultaneously.

Treating victims of trafficking as criminals deeply undermines their need for protection and, while perpetuating the crime, it may create impunity for traffickers. It also exacerbates existing fears the victims may have of law enforcement and authorities, making it less likely that they will cooperate in further investigations ( Anti-Slavery, 2014).

Cases of trafficking children for exploitation in forced begging or other forced criminal activities are often considered as public order issues or petty property crimes. Such a perception is highly risky as it increases the opportunity for victims to be considered as perpetrators, rather than victims. In response, the European Union has issued a directive which requires its Member States to give prosecutors and courts discretion not to prosecute in cases where someone has committed an offence as a result of being a victim of trafficking: European Commission, Child trafficking for exploitation in forced criminal activities and forced begging (October 2014); Article 8 of the EU Directive on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims (Directive 2011/36/EU).

It should be kept in mind that interviews with practitioners confirm that culture and national context (including religion) are often highly relevant in determining whether a particular situation is identified as a form of trafficking-related exploitation. These factors appear to be especially relevant in relation to sexual exploitation and other forms of exploitation particularly affecting women and girls. For example, in States where prostitution is considered inherently exploitative there are indications of a relatively greater willingness to view situations of prostitution as indicative or predictive of trafficking for purposes of sexual exploitation. In these States sexual exploitation may be considered "worse" than other forms of exploitation.

In some States, the concept of a "forced or servile marriage" is inimical to national culture and tradition and practitioners were clear that extreme circumstances would be required to trigger investigation of a marriage for trafficking-related exploitation. Cultural and context specific considerations can also be of significant importance in cases affecting men and boys. Cultural considerations also play a role in determining whether other forms of marriage (such as child marriage or temporary marriage) will be considered as exploitative.

Religion and ethnicity can also play a role in determining whether a particular practice meets the threshold of exploitation within the context of trafficking. For example, practitioners in one State noted that practices such as child marriage and child begging might be viewed differently depending on the ethnic background of those involved. This can result in a reverse kind of discrimination, where exploitation that would not be tolerated within the mainstream culture is viewed as somehow more acceptable if it involves particular ethnic minorities. The exploitation of migrant workers was acknowledged by some to have been "normalized" in the national culture to the point that it would not quickly be considered trafficking, particularly when compared to a situation involving a national.

With only a few exceptions, practitioners affirm the need to retain a degree of flexibility in defining and understanding trafficking-related exploitation. Many pointed to the emergence of new or hidden forms of exploitation, changes in criminal methodology and improvement in understanding of how exploitation happens as factors underlining the importance of such an approach. However, it was also noted (by noticeably fewer practitioners) that vague law is not good law: that basic principles of legality and justice require crimes to be described with certainty. The question of how these two important principles could be reconciled was not addressed. (UNODC, The Concept of 'Exploitation' in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol: Issue Paper (2015).