The digital forensics process involves the: search, acquisition, preservation, and maintenance of digital evidence; description, explanation and establishment of the origin of digital evidence and its significance; the analysis of evidence and its validity, reliability, and relevance to the case; and the reporting of evidence pertinent to the case (Maras, 2014).

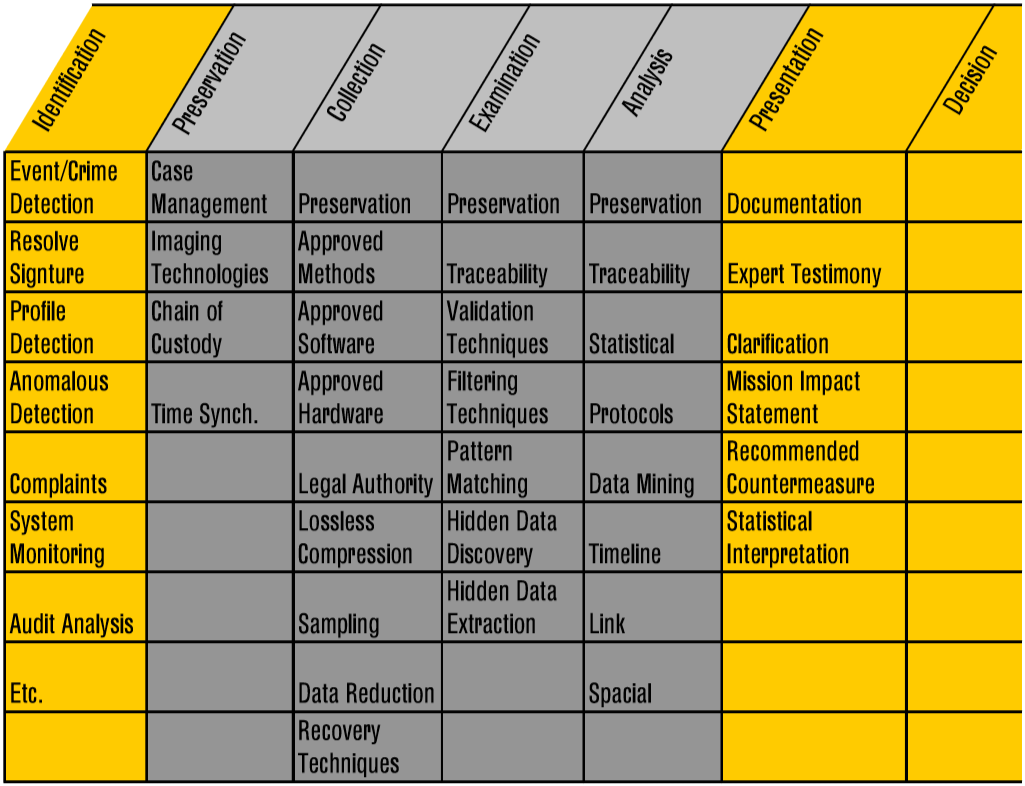

Various digital forensics methodologies have been developed and adopted. In 2001, the Digital Forensic Research Workshop, "a non-profit, volunteer organization, ….[dedicated to] sponsoring technical working groups, annual conferences and challenges to help drive the direction of research and development," developed a model based on the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation's protocol for physical crime scene searches, which includes seven phases: identification, preservation, collection, examination, analysis, presentation, and decision (Palmer, 2001, p. 14) (see Figure 1).

In 2002, another digital forensics model was proposed, which was based on the 2001 Digital Forensic Research Workshop model and the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation's crime scene search protocol (for physical crime scenes) (Reith, Carr, and Gunsch, 2002). This model ("The Abstract Digital Forensics Model") had nine phases (Baryamureeba and Tushabe, 2004, 3):

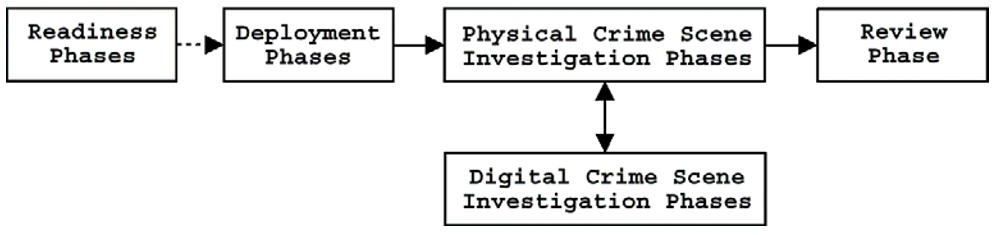

In 2003, the Integrated Digital Investigation Model (see Figure 2) was proposed, which is a more holistic investigative approach that has five basic stages, each with its own phases (Carrier and Spafford, 2003): readiness (i.e., assess ability of operations and infrastructure to support investigation); deployment (i.e., incident detected, appropriate personnel notified, and authorization for investigation is obtained - e.g., legal order for law enforcement investigations, supervisor authorization for private investigations); physical crime scene investigation (i.e., secure crime scene, identify relevant physical evidence, document crime scene, collect physical evidence at crime scene, examine this evidence, reconstruct crime scene events, and present findings in court); digital crime scene investigation (i.e., secure and identify relevant digital evidence, document the evidence, acquire, and analyse it, reconstruct events, and present findings in court); and review (i.e., once the investigation is concluded, an assessment is made to identify lessons learned).

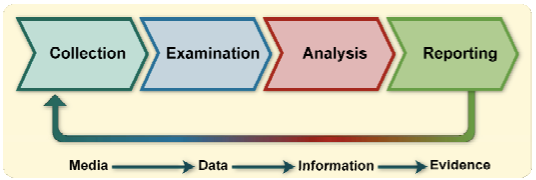

In 2006, the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology proposed a four-phase digital forensics model (see Figure 3) in its Guide to Integrating Forensic Techniques into Incident Response (SP 800-86) (Kent et al., 2006, 3-1): the collection phase, which includes the identification of evidence at the scene, and its labelling, documentation, and ultimate collection; examination phase wherein the appropriate forensic tools and techniques to be used to extract relevant digital evidence, while preserving its integrity, are determined; analysis phase whereby the evidence extracted is evaluated to determine its usefulness and applicability to the case; and the reporting phase, which includes the actions performed during the digital forensics process and the presentation of the findings.

Another investigative model was proposed by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) of the United States Department of Justice in 2001 and revised in 2008. Particularly, the NIJ's Electronic Crime Scene Investigation: A Guide for First Responders focuses on physical crime scene procedures, such as securing and evaluating the crime scene (i.e., to identify relevant devices with potential digital evidence), documenting the crime scene, collecting relevant devices, and packaging, transporting, and ultimately safeguarding devices.

The above-mentioned models are based on the assumptions that all of the phases are completed for each crime and cybercrime investigation (Rogers et al., 2006). In practice, however, this is not always the case. Because the volumes of data and the digital devices collecting, storing, and sharing data have exponentially expanded, resulting in more criminal cases involving some type of digital device, it is increasingly being considered impractical to conduct in-depth examinations of each digital device. As Casey, Ferraro, and Nguyen (2009) pointed out, "few [digital forensics laboratories] can still afford to create a forensic duplicate of every piece of media and perform an in-depth forensic examination of all data on those media… It makes little sense to wait for the review of each piece of media if only a handful of them will provide data of evidentiary significance" (p. 1353).

In view of that, digital forensics process models have been developed that take this into consideration. For instance, Rogers et. al (2006) proposed the Cyber Forensic Field Triage Process Model (CFFTPM), "an onsite or field approach" digital forensics process model "for providing the identification, analysis and interpretation of digital evidence in a short time frame, without the requirement of having to take the system(s)/media back to the lab for an in-depth examination or acquiring a complete forensic image(s)" (p. 19). Building on this model, Casey, Ferraro, and Nguyen (2009) proposed "three levels of forensic examination" that can be used in the field or in the lab:

The viability and relevance of each model and its components continues to be debated today (Valjarevic and Venter, 2015; Du, Le-Khac, and Scanlon, 2017). The reality is that each country follows its own digital forensics standards, protocols and procedures. However, differences in processes serve as an impediment to international cooperation in law enforcement investigations (see Module 7 on International Cooperation against Cybercrime).