On 13 June 2011, the French authorities requested the help of the Moroccan Direction Générale de la Sûreté Nationale - the countries' national security agency - to organize a controlled delivery. This operation sought to dismantle a criminal organization specialized in drug trafficking between Morocco and the Paris region, in France. The investigation established that the head of the criminal organization had appointed a French national to supervise the transport of an unknown amount of controlled drugs. The drug was concealed in an oil cargo, in an "Iveco" van. On 18 June 2011, the police forces of the Tanger-Med seaport eased the transit of the van. Once it reached Séte, in Southern France, the van was closely monitored until reaching the location of the cargo's unloading. As a result of this controlled delivery, 11 people were apprehended in several cities in France and a large quantity of cannabis resin was seized.

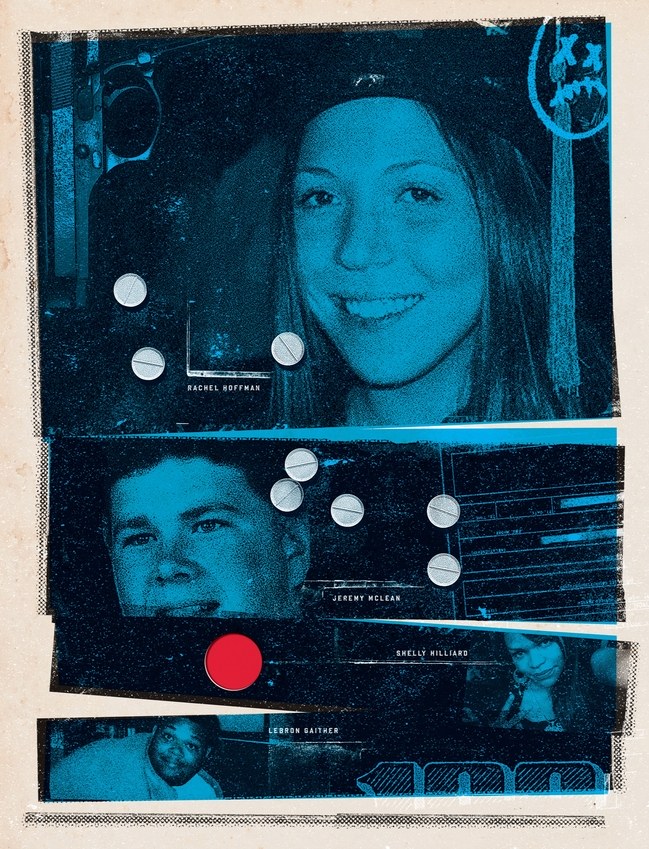

Read excerpts from the article " The Throwaways" that describes the Rachel Hoffman's case written by Sarah Stillman for the New Yorker in 2012:

On the evening of May 7, 2008, a twenty-three-year-old woman named Rachel Hoffman got into her silver Volvo sedan, put on calming jam-band music, and headed north to a public park in Tallahassee, Florida. A recent graduate of Florida State, she was dressed to blend into a crowd - bluejeans, green-and-white patterned T-shirt, black Reef flip-flops. On the passenger seat beside her was a handbag that contained thirteen thousand dollars in marked bills.

Before she reached the Georgia-peach stands and Tupelo-honey venders on North Meridian Road, she texted her boyfriend. "I just got wired up," she wrote at 6:34 p.m. "Wish me luck I'm on my way."

"Good luck babe!" he replied. "Call me and let me know what's up."

"It's about to go down," she texted back.

Behind the park's oaks and blooming crape myrtles, the sun was beginning to set. Young mothers were pushing strollers near the baseball diamonds; kids were running amok on the playground. As Hoffman spoke on her iPhone to the man she was on her way to meet, her voice was filtered through a wire that was hidden in her purse. "I'm pulling into the park with the tennis courts now," she said, sounding casual.

Perhaps what put her at ease was the knowledge that nineteen law-enforcement agents were tracking her every move, and that a Drug Enforcement Administration surveillance plane was circling overhead. In any case, Rachel Hoffman, a tall, wide-eyed redhead, was by nature laid-back and trusting. She was not a trained narcotics operative. On her Facebook page you could see her dancing at music festivals with a big, goofy smile, and the faux profile she'd made for her cat ("Favorite music: cat stevens, straycat blues, pussycat dolls").

A few weeks earlier, police officers had arrived at her apartment after someone complained about the smell of marijuana and voiced suspicion that she was selling drugs. When they asked if she had any illegal substances inside, Hoffman said yes and allowed them in to search. The cops seized slightly more than five ounces of pot and several Ecstasy and Valium pills, tucked beneath the cushions of her couch. Hoffman could face serious prison time for felony charges, including "possession of cannabis with intent to sell" and "maintaining a drug house." The officer in charge, a sandy-haired vice cop named Ryan Pender, told her that she might be able to help herself if she provided "substantial assistance" to the city's narcotics team. She believed that any charges against her could be reduced, or even dropped. (…)

Hoffman chose to cooperate. She had never fired a gun or handled a significant stash of hard drugs. Now she was on her way to conduct a major undercover deal for the Tallahassee Police Department, meeting two convicted felons alone in her car to buy two and a half ounces of cocaine, fifteen hundred Ecstasy pills, and a semi-automatic handgun.

The operation did not go as intended. By the end of the hour, police lost track of her and her car. Late that night, they arrived at her boyfriend's town house and asked him if Hoffman was inside. They wanted to know if she might have run off with the money. Her boyfriend didn't know where she was. (…)

Two days after Hoffman disappeared, her body was found in Perry, Florida, a small town some fifty miles southeast of Tallahassee, in a ravine overgrown with tangled vines. Draped in an improvised shroud made from her Grateful Dead sweatshirt and an orange-and-purple sleeping bag, Hoffman had been shot five times in the chest and head with the gun that the police had sent her to buy.

By the evening of her death, Rachel Hoffman had been working for the police department for almost three weeks. In bureaucratic terms, she was Confidential Informant No. 1129, or C.I. Hoffman. In legal parlance, she was a "cooperator", one of thousands of people who, each year, help the police build cases against others, often in exchange for a promise of leniency in the criminal-justice system.

In 2009, the so-called "Rachel's Law" was passed by the Florida State Senate, requiring law enforcement agencies to provide special training to officers who recruit confidential informants, instruct informants that reduced sentences may not be provided in exchange for their work, and permit informants to request a lawyer if they want one.

There have been allegations that police officers misuse their powers to set up and punish sex workers through entrapment. In some countries, undercover police officers are permitted to receive certain sexual services from sex workers in the course of their work to secure evidence. Several sex workers have reported that police charged them with solicitation even though the officer initiated the exchange and offered to purchase sex.

Furthermore, allegedly police officers in some countries threatened to report sex workers to their spouses, parents or children if they did not confess. Sex workers and their advocates have also reported that police mislead sex workers about the consequences of their confessions, coercing them to sign statements while withholding the fact that an admission of guilt would likely lead to imprisonment. In some cases, police seized condoms as evidence.

Read the short text " Edward Snowden: Traitor or Hero?" written by Andrew Carlson from the University of Texas at Austin:

In 2013, computer expert and former CIA systems administrator, Edward Snowden released confidential government documents to the press about the existence of government surveillance programs. According to many legal experts, and the U.S. government, his actions violated the Espionage Act of 1917, which identified the leak of State secrets as an act of treason. Yet despite the fact that he broke the law, Snowden argued that he had a moral obligation to act. He gave a justification for his "whistleblowing" by stating that he had a duty "to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them." According to Snowden, the government's violation of privacy had to be exposed regardless of legality.

Many agreed with Snowden. Jesselyn Radack of the Government Accountability Project defended his actions as ethical, arguing that he acted from a sense of public good. Radack said, "Snowden may have violated a secrecy agreement, which is not a loyalty oath but a contract, and a less important one than the social contract a democracy has with its citizenry." Others argued that even if he was legally culpable, he was not ethically culpable because the law itself was unjust and unconstitutional.

The Attorney General of the United States, Eric Holder, did not find Snowden's rationale convincing. Holder stated, "He broke the law. He caused harm to our national security and I think that he has to be held accountable for his actions."

Journalists were conflicted about the ethical implications of Snowden's actions. The editorial board of The New York Times stated, "He may have committed a crime…but he has done his country a great service." In an Op-ed in the same newspaper, Ed Morrissey argued that Snowden was not a hero, but a criminal: "by leaking information about the behavior rather than reporting it through legal channels, Snowden chose to break the law." According to Morrissey, Snowden should be prosecuted for his actions, arguing that his actions broke a law "intended to keep legitimate national-security data and assets safe from our enemies; it is intended to keep Americans safe."

Around June 2000, the FBI set up Invita, a sting operation posing as a computer security company in Seattle, Washington. Defendant Vasiliy Gorshkov and Mr. Alexey Ivanov flew from Russia to Seattle, where they met with undercover FBI agents at the Invita office. During the meeting, Gorshkov used an FBI laptop computer to demonstrate his computer hacking and computer security skills. He also accessed his computer system in Russia. After the meeting, both men were arrested.

Following the arrest and without Gorshkov's knowledge or consent, the FBI searched and seized the laptop and all the keystrokes made by Gorshkov. The FBI then obtained Gorshkov's username and password that he had used to access the Russian computer. Using the login information, the FBI logged onto the defendant's computer system in Russia and downloaded the file contents of the computer(s) without previously obtaining a warrant.

According to the indictment, Ivanov and Gorshkov had defrauded PayPal through a scheme in which stolen credit cards were used to generate cash and to pay for computer parts purchased from vendors in the United States. The FBI's undercover operation was established to entice Ivanov and his accomplices responsible for these crimes to travel to U.S. territory.

The Court found that the defendant could not have had an actual expectation of privacy in a private computer network belonging to a U.S. company, Invita, and a computer that was not his. In addition, the defendant knew that the systems administrator could and likely would monitor his activities over Invita's network.

Additionally, the court held that FBI's actions were reasonable under the exigent circumstances. A previous judgment concluded that an unlawful temporary seizure is allowed if supported by probable cause and designed to prevent the loss of evidence while police obtain a warrant in a reasonable period of time. In this case, the agents had a good reason to fear that co-conspirators would and could destroy evidence, or make it unavailable since electronic data and evidence can be moved to a different computer with ease, and access to it could be prevented with a mere change of password or pull of the power plug.

Gorshkov and Ivanov were sentenced to serve 36 months in prison on 20 counts of conspiracy, various computer crimes, and fraud. Gorshkov was also ordered to pay restitution of nearly $700,000 for the losses he caused to Speakeasy and PayPal.

Oleg Morari, a Moldovan national, was convicted of participating in the production of a false Romanian identity card in December 2008. His conviction was based on evidence obtained during an undercover operation. In January 2008, the Balti police had placed an advertisement in a newspaper concerning help in obtaining passports to which Morari had replied. Following the telephone call, he met with an undercover agent who told him that he was looking to obtain a Romanian passport. The two men agreed to keep one another informed if they found an easy way to obtain a passport.

A few weeks later the agent contacted Morari to enquire whether he had made any progress in his search. Morari informed the agent that he had found a person who could help and agreed to act as an intermediary after the agent refused to contact this person directly and proposed a deal involving one of his acquaintances (another undercover agent). Upon concluding the deal in April 2008, he was arrested by the police.

The first-instance court did not consider Morari's entrapment plea. The two higher courts which examined his appeal and appeal on points of law (in March 2009 and July 2009, respectively) examined his allegation of entrapment but dismissed it on the ground that it was Morari who had been the first to call the telephone number in the advertisement. All the courts refused to hear the undercover agents, finding that according to the law, they could be heard only if they consented to having their identities disclosed.

Relying on article 6§1 ("right to a fair trial") of the European Convention on Human Rights, Morari alleged that he had been a victim of police entrapment and that the courts had failed to examine this complaint in the proceedings against him. The European Court of Human Rights declared the application admissible and held that there was a violation of article 6§1 of the Convention. The Court held that the respondent State was to pay the applicant the following amounts: (i) EUR 3,500, plus any tax that may be chargeable, in respect of non-pecuniary damage; (ii) EUR 1,820, plus any tax that may be chargeable, in respect of costs and expenses.

In November 2014, a coordinated international operation led to the arrest of 118 individuals in connection with an online fraudulent scheme against airline companies. The operation was carried out at more than 80 airports and involved over 60 airlines and 45 countries. The investigation was coordinated by Europol, INTERPOL and AMERIPOL.

The suspects allegedly purchased plane tickets using stolen or fake credit cards generating losses of USD 1 billion. The investigation revealed that the fraudulent scheme was in several cases connected to other crimes, such as drug and human trafficking.

The airline and credit card companies involved participated actively in meetings with law enforcement at Europol's European Cybercrime Centre (EC3). The companies provided investigators with information contained in their databases. This partnership allowed law enforcement to identify 281 suspicious transactions.

An extensive international network allowed investigators to trace the suspects. The International Air Transport Association provided information on individuals using fraudulently obtained tickets. INTERPOL played a crucial role in identifying wanted persons and stolen documents. Europol officers were active at several European airports as well as in Singapore and Bogota.

Regional perspective: Pacific Islands RegionCase Study 8 (Specialized Enforcement Units' Coordination, Fiji)Three citizens of Bulgaria, who entered Fiji posing as tourists in November 2017, were arrested and convicted a few weeks after for their involvement in an automated teller machines (ATM) scam. The coordinated action of several Fiji's specialized enforcement units was essential to the speedy resolution of the case. On November 8, 2017, Mr. Velikov and Mr. Petrov arrived in Lautoka, Fiji from Auckland, New Zealand. A Customs officer at the airport, noting they were acting suspiciously, questioned them and found them in possession of extensive electronic equipment. They were let into the country, but the officer alerted the Transnational Crime Unit (TCU) for surveillance. The following day, Mr. Minchev also arrived from Auckland. Customs officers opened his luggage and found various electronic equipment together with different types of credit cards, sim cards, magnetic cards, and paper sand, among other things. Customs officers photographed the contents of the bag and released it to him. He joined Velikov and Petrov for breakfast, checking in the same hotel. Afterward, the three took turns placing skimming devices in the ATMs around the Lautoka, Nadi and Namaka corridor. An electronic skimming device attached to the card slot was found in the Bred Bank ATM on the 11 th and immediately reported to the police. On November 12, Mr. Minchev and Mr. Petrov were arrested. On the next day, alerted police officers prevented Mr. Velikov to board a Korean Airlines flight, frustrating his intent to run away. The Cyber Crime Unit of the Police Department examined all devices and found unauthorized PINs of Bred Bank's customers in Minchev's laptop. The defendants were charged with one count of possession of skimming device with intent to dishonestly obtain personal financial information, one count of unauthorized access to restricted data, and one count of attempt of unauthorized access of restricted data. They pled guilty and were sentenced to 12 months and six days in prison. Case-related filesSpecial feature

Discussion questions

Case Study 9 (Controlled Buys, Palau)The Supreme Court of Palau decided Buck v Republic of Palau on December 10, 2018. In the case, Arnold Buck appealed his conviction to fifty-seven years of imprisonment on drug-related charges on the grounds of entrapment and failure to disclose Brady evidence in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Palau Constitution and the rules of Criminal Procedure. Mr. Buck's charges arose from three controlled buys of methamphetamine that occurred in 2016. The sentence explains that "controlled buy" is the term used by Belau Drug Enforcement Task Force officers to describe the procedure by which a confidential informant purchases an illegal controlled substance from individuals under police investigation using marked bills. Two confidential informants were involved in the operations that ended with Mr. Buck's convictions, and both were given incentives to participate: one of them was promised an immunity agreement, and the other received monetary compensation. Both men testified at Mr. Buck's trial. While it was unclear what information was provided to the defense regarding the immunity agreement, it was undisputed that the prosecution failed to disclose the payments received by the confidential informant in exchange for cooperation. This information was revealed mid-trial during the defense's cross-examination of a Task Force officer. The defense moved to request a judgement of acquittal for all charges, arguing that Mr. Bucks had been improperly pre-targeted for a controlled buy and that the prosecution failed to disclose the payments. The Trial Division denied the motions; a strong conviction followed. The Supreme Court considered that entrapment, as an affirmative defense, cannot be raised on appeal and affirmed Mr. Bucks' convictions on the charges not related to the operation in which the confidential informant was paid. Subsequently, in a thorough analysis of the Brady doctrine (which states the prosecution's Due Process obligation to disclose evidence favourable to the defense), the Court considered that the prosecution's suppression of the payments indeed violated Mr. Bucks' constitutional rights, since "being paid to produce evidence" opens avenues "into the legitimacy of the investigation and possible defense strategies." The Court vacated the sentence on the charges related to the testimony of this confidential informant and remanded the case for consistent proceedings. Case-related files

Special features

Discussion questions

Exercise 1 (Undercover Operations)In the Marsters landmark case analysed in the previous Module-jurisdiction the Cook Islands-the sentencing judge pondered the nature of undercover operations conducted by the police which had been questioned by the defendant. Read and discuss the following extract of the sentence, and argue why going undercover is a technique utilized by law enforcement agencies combating organized crime: "[53] Before I come to dealing with each of you individually I must make comment on things that counsel has raised on your behalf. I have already dealt with his view of Cook Islands sentencing standards. He also made comment relating to the nature of the operation by the Police. It involved, as I have said, eighteen police from New Zealand. Of significance, at least one of those was what is termed 'undercover', and Mr George [defendants' lawyer, added] on your behalf has complained about these tactics - "they are new, they are strange, and they are socially repugnant" [emphasis added] were his words. [54] Those who are apprehended by these operations might not appreciate them. That is understandable because they get caught. But there is nothing inherently, in my view at least, strange or socially repugnant about someone being embedded into an operation such as this." Case-related files |

Regional perspective: Eastern and Southern AfricaCase Study 10 (What constitutes entrapment? - South Africa)Mr. Akash Lachman was convicted on a charge of corruption by a regional Court of South Africa. The South African Eastern Cape High Court upheld his conviction. The essence of the charge was that, whilst employed as an auditor in the East London office of the South African Revenue Service (SARS), Lachman corruptly attempted to solicit a bribe from Victim One as a reward for assisting the latter to make his tax problems ‘go away’. Firstly, Lachman telephonically requested Victim One to provide specific tax information. The two later met at the SARS offices and, soon after that, Victim One started receiving anonymous SMSs through which he was asked to pay a hefty amount of money to make the tax issues disappear. In three weeks, Victim One received more than 200 messages from the same phone number. In one of the messages, Victim One was requested to drop the money at the SARS offices in an envelope addressed to Ms. Fellows, the team leader of the audit section. Victim One reached out to his lawyer as well as a private investigator, and reported the matter to the police. The Organized Crime Unit of the South African Police Service advised him to play along and deliver the envelope, setting up a covert operation. Victim One did so, accompanied by undercover police officers who arrested Lachman at the premises when he came to claim the envelope. Lachman was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. He challenged his conviction claiming that he was unlawfully entrapped, the evidence was inadmissible, and that his search had been unlawful too. The South African Supreme Court of Appeal took the opportunity to clarify what is “a trap”, referring to the dictum by Holmes JA in the case S v Malinga & others, where a trap was described as: […] a person who, with a view to securing the conviction of another, proposes certain criminal conduct to him, and himself ostensibly takes part therein. In other words he creates the occasion for someone else to commit the offence. The Court also recalled the High Court reasoning in the distinction of three different scenarios: 1) The first scenario is when the trap creates the opportunity to commit a crime for someone who, but for the trap, would not have committed the crime; 2) A second scenario occurs where the trap merely creates such an opportunity for someone who wanted to commit the particular offence and would have done so in any event, even without the trap’s influence; 3) A third category is when the accused is the initiator of the incriminating transaction and instigates the trap to conclude the transaction with him or her and the trap merely ostensibly participates therein, and in that sense creates the opportunity for the commission of the crime. The accused, in such a case, commits the crime without any influence from the trap. The Supreme Court of Appeal equated the police operation in the case to a “controlled delivery” and ruled that it fell within the third category. The appeal was dismissed. Case-related files

Significant features

Discussion questions

[32] This scenario is analogous to the situation where a kidnapper demands a ransom from the kidnapped victim’s family. If the family should inform the police of the prearranged time and venue for delivery of the ransom, could it ever be suggested that the police used the victim’s family as a trap if the police should turn up to witness the delivery of the ransom and to arrest the culprit? The answer must surely be no. What other situations could you think to exemplify the typology provided by the Court?

Case study 11 (The Akasha Brothers - Kenya, United States)Baktash Akasha Abdalla and his brother, Ibrahim Akasha Abdalla, were the leader and deputy of a sophisticated international drug trafficking network, responsible for tons of narcotics shipments throughout the world. For over twenty years, they manufactured and distributed drugs and engaged in acts of violence toward those who posed a threat to their enterprise. When the brothers encountered legal interference, they bribed Kenyan officials —including judges, prosecutors, and police officers—to avoid extradition to the United States. The brothers, along with two associates, were arrested in Mombasa by Kenyan Anti-Narcotics Unit officers in 2014, after providing 99 kilograms of heroin and two kilograms of methamphetamine to confidential sources posing as representatives of a South American drug cartel at the direction of the USA Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Following the arrests and pending extradition proceedings, the Akasha brothers continued criminal operations, using profits to bribe Kenyan officials. In 2017 the brothers were expelled from Kenya and DEA agents took them to the United States for prosecution. In October 2018, Baktash and Ibrahim Akasha pled guilty in a United States Federal Court to conspiring to import and importing heroin and methamphetamine, conspiring to use and carry machineguns and destructive devices in connection with their drug-trafficking crimes, and obstructing justice. In August 2019, Baktash was convicted to 25 years in prison and ordered to pay a $100,000 fine. In 2020, his brother Ibrahim received a sentence of 23 years in prison. Case-related files

Significant features

Discussion questions

|