The Protocol against Trafficking in Persons, which supplements the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), is the primary legal instrument concerning trafficking in persons. It was adopted by the General Assembly under resolution 55/25 on 15 November 2000 and came into force on 25 December 2003.

The Protocol contains a preamble and 30 articles. The preamble recognizes that "despite the existence of a variety of international instruments containing rules and practical measures to combat the exploitation of persons, especially women and children, there is no universal instrument that addresses all aspects of trafficking in persons". The Preamble also acknowledges that "effective action to prevent and combat trafficking in persons, especially women and children, requires a comprehensive international approach in the countries of origin, transit and destination that includes measures to prevent such trafficking, to punish the traffickers and to protect the victims of such trafficking, including by protecting their internationally recognized human rights".

The purposes of the Protocol are prescribed in article 2:

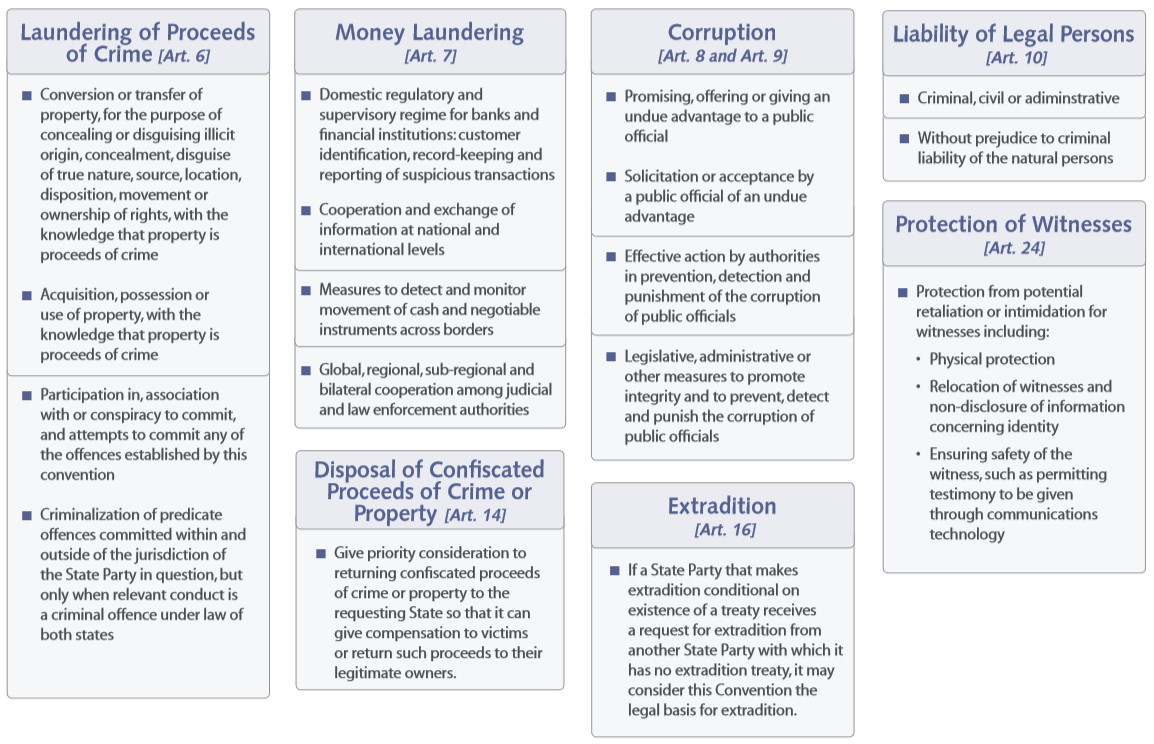

The Protocol against Trafficking in Persons supplements UNTOC (see Module 1 on the Definition of Organized Crime). Consequently, as stated in article 1 of the Protocol, both documents should be interpreted and applied together. The following provisions of UNTOC are directly relevant to application of the Protocol:

The case illustrated in Box 2 below shows the role of corruption in a case of trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

M. was a minor female from Moldova who was trafficked to the Balkans where she was sexually exploited and held in a brothel until she was rescued by a human trafficking task force operating with the assistance of the international community. M.'s trafficking had been allegedly facilitated by corruption in three different ways.

First, actual blank passports had been allegedly corruptly obtained by her traffickers from a neighbouring Balkan country and used to transfer her into the location where she was sexually exploited.

Second, even though the passports were filled out incorrectly and obviously improper, with the wrong official stamps and other glaring mistakes, and even though M. did not speak any of the local languages of where she was exploited, she was passed through several border crossings without question, allegedly through corrupt facilitation.

Third, the brothel where M. was exploited was across the street from the local police station. No action to investigate was taken; some police officers were allegedly obtaining sexual services from M. and other victims of trafficking.

M. was freed based on a national level investigation undertaken with international support without the participation of the local authorities.

Prior to the adoption of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons in 2000, other international conventions and declarations addressed some aspects of trafficking. Many of these are still relevant today. They help ground a comprehensive response to trafficking in persons, complementing and adding to the requirements of the Protocol. They are listed in Box 3 below.

However, these international instruments may be differentiated from the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons in the following ways:

Article 34(1) of UNTOC requires States parties to take all necessary measures (including legislative and administrative measures) to ensure the implementation of their obligations under the Convention. Article 34(2) requires States parties to enact legislation under their national law to criminalize the activities described in articles 5, 6, 8 and 23 of the Convention"independently of the transnational nature or the involvement of an organized criminal group".

Article 4 of the Protocol provides that "the Protocol shall apply, except as otherwise stated herein, to the prevention, investigation and prosecution of the offences established in accordance with article 6 of this Protocol, where the offences are transnational in nature and involve an organized criminal group, as well as to the protection of the rights of persons who have been the object of such offences".

The definition of trafficking in the Protocol has been widely adopted by many countries in their national laws. However, certain difficulties have persisted in interpretation of aspects of the definition (for example, the interplay between the use of prohibited "means" and victim consent as a potential defence, and what is meant by "purpose of exploitation" and "abuse of a position of vulnerability"). States must prioritize addressing and resolving these issues in their legislation and case law because characterizing certain conduct as trafficking has important consequences for both perpetrators and victims. Some support a conservative or restrictive interpretation of the concept of trafficking while others advocate for its expansion. The former position is concerned that having too wide a definition may result in the inclusion of practices not meeting the grave offence threshold of "trafficking in persons". The latter position opines that too narrow a definition may prevent investigation, prosecution and conviction for practices that should indeed fall under the definition trafficking or may exclude such practices altogether ( UNODC, 2014).

In addition to UNTOC, the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons and national legislation, a few regional initiatives were designed to address trafficking. For example, in 2005 the Council of Europe adopted the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings. Article 39 addresses the relationship between this Convention and the Protocol. It states that the Convention does not affect the rights and obligations of States under the Protocol, but is intended to enhance the protection afforded by it and further develop the standards contained within it. The 2015 ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, and the 2002 SAARC Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution provide a regional legal framework in Asia.

In regions where no specific regional legal instrument addresses trafficking in persons, other documents may be refered to. In the Arab region, the Arab Model Law on Combating Human Trafficking and the Arab Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking were both adopted in 2012. In Africa, several time-bound plans of action were adopted in the last years, such as the Ouagadougou Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Human Beings (2006) which aimed to prevent and combat trafficking between the European Union and the African Union, or the the ECOWAS Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (2002) or the SADC Strategic Plan of Action on Combatting Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (2009).

A number of internationally recognized, albeit non-binding principles and guidelines, aid interpretation of the Protocol and guide the implementation of measures to combat trafficking and protect trafficked persons. For example, in 2003 the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights released Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking, which call upon States to "adopt appropriate legislative and other measures necessary to establish, as criminal offenses, trafficking, its component acts and related conduct" in accordance with the rules stipulated in the Protocol. The Recommended Principles and Guidelines provide that "the lack of specific and/or adequate legislation on trafficking at the national level has been identified as one of the major obstacles in the fight against trafficking. There is an urgent need to harmonize legal definitions, procedures and cooperation at the national and regional levels in accordance with international standards". There are also a host of policies, guidelines and manuals published by various international entities, including UNODC, IOM, UNICEF, UNHCR, OSCE, regional initiatives, such as the Bali Process, as well as numerous non-government organizations.

As noted above, article 3(a) of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons defines trafficking in persons as follows:

Trafficking in Persons shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include at a minimum the exploitation of prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of human organs.

Although article 5 of the Protocol requires each State to enact national legislation to criminalize the conduct described in article 3, that legislation need not follow the language of the Protocol verbatim , but should be adapted in accordance with national legal systems to give effect to the concepts contained in the Protocol.

The following aspects of the definition in article 3 are worth emphazising:

Operation Golf began in the UK during 2005 when officers started examining a spectacular growth of petty crime in Central London, such as robbery, pick-pocketing and street crime. One major finding was that a lot of these crimes were being conducted by Roma children, as young as 6. In the UK, no child can be prosecuted under 10. The police found that when caught, the Roma children over 10 pretended to be younger, and provided false documents and names. When children were brought in, officers couldn't track down their parents to come and pick them up. With 60% of the children arrested, the person coming to represent them was not a family member. Excuses of parents not being able to speak English, parents being back in Romania for a funeral, etc. were often heard. The UK started working with Romania to identify the problem. There was already an investigation ongoing there into over 1,000 children who were removed from one town alone in 2005-2006. Romanian officers had already mapped who were behind these removals. They however did not know where the children had gone. 1,017 "lost" children were put on a list in Romania, labelled as "children of whom Romania was concerned that they were trafficked". Once the UK started examining this further, they found in 2007 that 200 of the children that were on this list had been reported as criminal offenders in the UK. Due to this discovery, London police then started investigating the possibility of them being trafficking victims. The results of these investigations were astonishing. Desperate Roma parents apparently "gave away" their children, after being approached by criminals offering them to take their child abroad. They were told that the child would make a lot of money abroad and would be able to send this money back to them. Parents might have even been told that the child would be begging and stealing, but in Roma culture this does not necessarily cause major objections. However, the parents would have to pay the criminals to take their child with them. Obviously they could not do so, so they went into debt bondage with major interests. After a while, the criminals would return to the parents' house and state that the child was not earning enough. They then would take more children who were also placed abroad, not necessarily together with their siblings. More loans would be agreed upon. The criminals would again return with the same message, until the entire family, including the parents would be placed abroad and turned into a "slave family", unable to pay off their debts to the criminals. All children would be separated, forced to beg and steal and hand over all their money. The elders would be forced to go out begging, stealing, and take care of many children whose parents were either still in Romania or had been taken elsewhere. In addition, the organized criminals would facilitate fraudulent claims for UK social benefits taking the proceeds to add to their wealth. Police found that the criminals behind these lucrative operations consisted of members of Roma clans, some of them independent organized groups. These clans are highly hierarchically organized, family and clan-based and with the heads of family running things from their gigantic houses back in Romania. Sometimes the clans work together, again if it is profitable and necessary, and the groups are expanding in members and territory because business is going so well. On the 1st of September 2008, a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) between Romania and the UK was formed, together with Eurojust and Europol to fight these clans and save the children from exploitation.