In addition to the categories of firearms listed in this Module, this category encompasses various types of firearms which may overlap with those mentioned but are deserving their own classification.

Firearms in this last generic category may borrow characteristics from the commonly accepted category, but their modality of production and/or modification makes them very difficult to be identified and traced. Weapons in this category also represent a legal challenge, either not being legally covered, especially in what concerns new technologies, or their transfer and possession is at the edge of the law or takes advantage of the existing legal loopholes.

An area of concern highlighted by both the Small Arms Survey (2018) and the UNODC Study on Firearms (2015), was that of 'craft weapons'. Essentially, the practice consists of weapons and ammunition being fabricated by hand in relatively small quantities. Artisanal in nature, they can range from pistols and shotguns to the more advanced assault rifles, and also include very expensive design weapons used for example in sport shooting or hunting.

In contrast to the craft or artisanal production, there are also the generically called rudimentary arms. These arms are generally homemade and are more likely to be found in criminal contexts. Rudimentary arms are essentially arms manufactured by parts or components that were not originally designed to be parts of a firearm or made out of parts from other firearms.

Gunsmiths and handcraft production can be found in all regions. For example, the Small Arms Survey highlighted some previous research carried out. 'The artisanal firearm industry is especially widespread and developed in Ghana, with some gunsmiths reportedly able to produce assault rifles' (Small Arms Survey, 2018). There are various state approaches regarding the handcraft production. While Ghana is making efforts to forbid these artisanal activities, in Burkina Faso, the state tries to regulate and record them.

'The Peshawar district in Pakistan (one of 22 districts in the North-West Frontier Province) is reportedly home to some 200 workshops producing a wide range of inexpensive small arms, including revolvers and shotguns' (Small Arms Survey, 2018).

In June 2018, Small Arms Survey released a briefing paper, which explored in some detail the wholesale market of craft production within Nigeria highlighting the inherent technological limitations of firearms legislation.

The most famous craft production site is in the city of Darra in Pakistan as presented in the video The Gun Market of Pakistan.

An area of concern for policymakers and law enforcement officials is the 3D printed firearm. In essence, the firearm is manufactured by building layer upon layer of plastic, for example, creating various complex and solid objects.

The Liberator, a single-shot gun, is an example of such technology.

Policy discussions have intensified, at national and international level, around the use of modern technology such as 3D printed arms, their potential impact on security, and the legal responses to them.

In 2016, Armament Research Services explored both the feasibility and capabilities of 3D firearms.

A 2018 3D Printed Gun Report released by All3DP, the world's leading 3D printing magazine, concludes that the threat of these arms remains rather limited. But they have some qualities that will make them more attractive to criminals. The material of these arms is difficult to detect by current detectors and scanners. These firearms are easy to destroy after a crime easy making almost impossible the recovery of the murder weapon. They are also untraceable. By putting together all these characteristics 3D printed weapons fulfill all conditions to become the perfect weapons for high profile crimes, once the technology will advance enough to make them safer and more technologically advanced.

The technological development and the availability of cheap but performant CNC machines and 3D printers will make the production of 3D firearms far simpler and more difficult to regulate against. 3D printers became very common and their use covers various fields. They are not per se an object that requires to be put under control, especially because the real problem is not so much the printer but the fact that the blueprint for the firearms can be easily and openly accessed through the Internet.

As far as the legal regime for these arms is concerned, there seems to be a gap in both domestic and international legislation, as in fact, no international legal instruments explicitly refer to them. In the absence of a more specific provision, the definition of illicit manufacturing provided by the Firearms Protocol can give some first indication. Clearly, 3D printed arms would fall under the scope of this provision. In practice, however, there remains a need to further define and legislate the phenomenon, especially as regards the issue of downloading or otherwise getting access to the blueprints to actually produce these arms.

Predictably, states have acted accordingly in addressing these technological challenges. Some countries have started to try to capture this new phenomenon in its domestic law: In the United States, the Undetectable Firearms Act of 1988 states that 'any firearm that cannot be detected by a metal detector is illegal to manufacture…' In practical terms, 3D printed firearms would need a metal plate inserted. Additional amendments to renew and expand the legislation have been mooted ( H.R. 1474 & S. 1149).

In the United Kingdom, the Firearms Act of 1968 'bans the manufacturing of guns and gun parts without government approval.' Additionally, the 2016 UK Guide on Firearms Licensing Law states that 'the manufacture, purchase, sale and possession of 3D printed firearms, ammunition or their component parts is fully captured by the provisions in section 57(1) of the Firearms.'

The unlicensed copies are encountered in situations when manufacturers either:

Small Arms Survey estimates that '530,000 to 580,000 military small arms are produced annually either under licence or as unlicensed copies.'

This is a form of illicit manufacturing. The unlicensed firearms are not registered, and they usually end up on the illicit market, being sold at a fraction of the price of the original firearm. Lack of registration or serial number duplication makes these weapons very difficult to trace using the conventional tracing methods through identification of firearm type, serial number, model and manufacturer.

A replica firearm is a device that is manufactured to resemble an existing design of a firearm but is not intended to fire. Typically, replica firearms are manufactured for firearm collectors, especially collectors of antique firearms.

An imitation firearm is a device that is not a real firearm, but that was designed to look exactly or almost exactly like a real firearm (some very realistic toy guns, some moulded guns either in rubber or metal). In some jurisdictions, imitation firearms are prohibited or are regulated in a similar fashion to firearms.

Although technically unable to produce harm as a result of shooting, both replica and imitation firearms have the capacity to intimidate since they can easily be mistaken for real firearms. Although they are not real firearms, due to the reasons outlined above, they are defined and specifically mentioned in various national legislations.

A deactivated firearm is any firearm that was modified in such a way that it can no longer fire and expel any form of projectile. Usually, the deactivation process has to be permanent. Because these deactivated firearms do not fall under the same regulations as the activated firearms, they are often purchased by criminal organizations who either remove the deactivation systems or convert the weapons with spare parts and the so reactivated firearms are entering the illicit market.

Conversion is a process that modifies a non-lethal (e.g. blank or gas weapon) into a lethal weapon that is further pushed into the illicit market.

Modular weapons are produced with components that are interchangeable in a way that can change or improve the characteristic of a firearm. In addition, changing essential components like the barrel, extractor/ejector, firing pin etc. will make ballistic identification extremely difficult, if not impossible.

One good example in this range is the Glock pistol, which, although not conceived as a modular weapon, bears the modularity characteristics and can be easily transformed from a semi-automatic pistol into a fully automatic sub-machine gun with 50 or 100 rounds magazine, scope, silencer, shall recovery system and other modular parts.

The term refers to firearms that have the resemblance of harmless items, but that can be lethally fired. As an example, the pen gun, the phone gun or the flashlight gun. Concealable firearms can be legally produced or can be crafted in an illicit way. Although those firearms that are legally produced are registered and theoretically can be traced, the main danger resides in their physical characteristics that makes them difficult to be recognized as a firearm, hence identification and detection possibilities are drastically reduced.

A kit weapon is usually made from a series of parts and components. In most situations the kit provides the components that require additional machining for full completion. Machining the kit for a firearms completion not only requires a certain level of technological skills but also opens an opportunity to build untraceable/unregistered weapons that can easily be diverted into the illicit market.

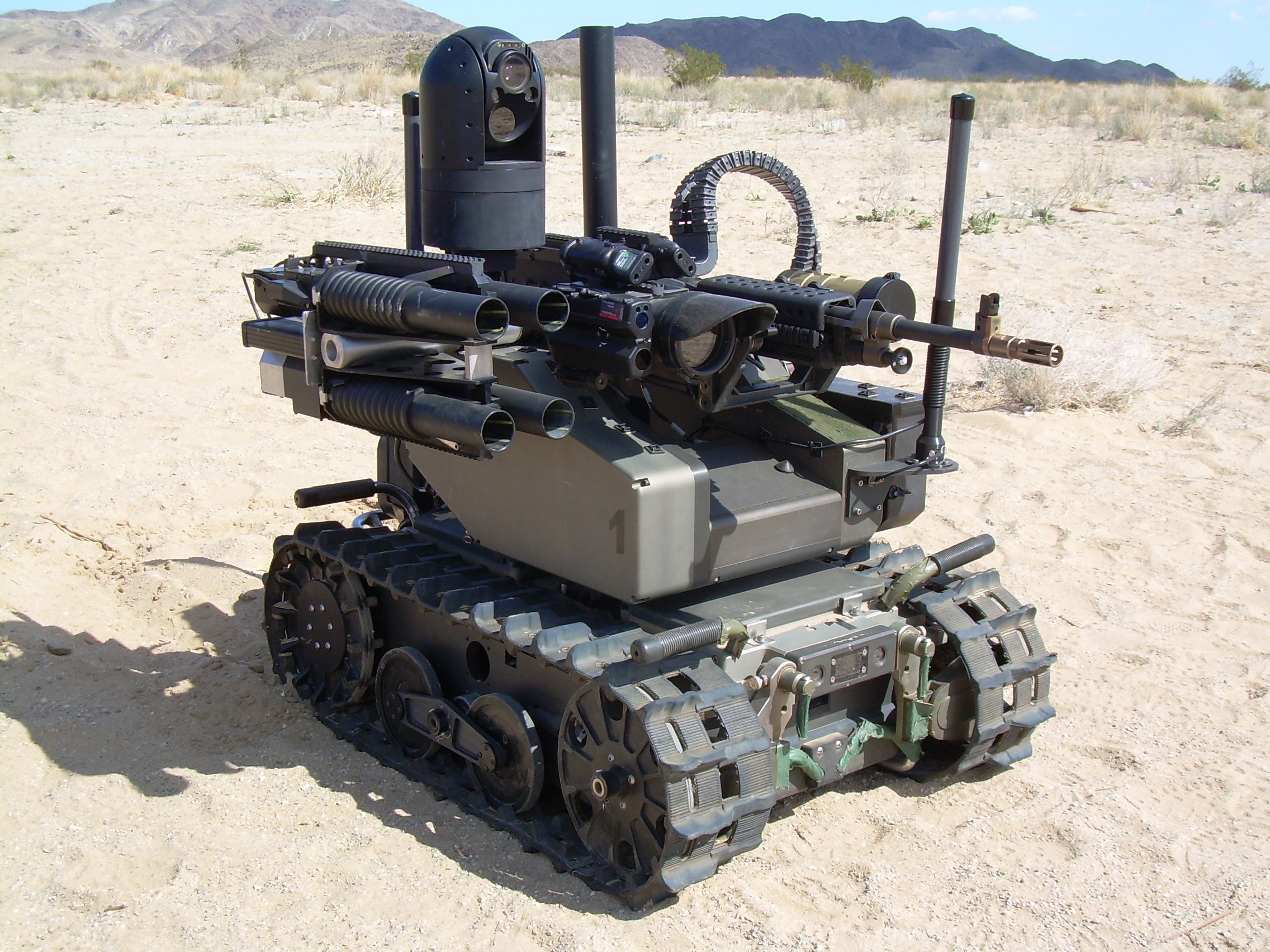

The accelerated development of artificial intelligence touched also the firearms realm. There are already advanced technical machines that are equipped with firearms, like drones and armoured vehicles, that are not equipped with human personnel, but nevertheless their control and action is exercised by humans.

The new idea behind fully autonomous weapons is to use artificial intelligence (AI) to control these weapons and eliminate the human control. Unfortunately, this idea brings a dark perspective to the horizon, as long as we are not aware what will be the level of human control, to what extent this human control will be effective over the AI systems and how AI may react in various conditions and environments.

In 2015, over a thousand researchers co-signed an open letter urging the United Nations to ban the development and use of autonomous weapons. Unfortunately, this development of semi-autonomous or even autonomous weapons is mostly secretive and it is unclear what part the humans will play in choosing and firing on targets, if any.

Although fully autonomous weapons do not officially exist, the idea itself created strong debates between the main powers, voices being raised pro and against this concept.

In 2013, the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) Meeting of State Parties decided that the Chairperson will convene in 2014 an informal Meeting of Experts to discuss the questions related to emerging technologies in the area of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS). In 2016, the Fifth Review Conference of the High Contracting Parties to the CCW established a Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on emerging technologies in the area of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) The United Nations is still considering imposing a ban on so called "killer robots" but the discussions are ongoing and an agreement has not been yet reached.

This is a topic that requires continuous attention and given the tremendous impact this technology may have, states shall prepare to give more consideration this category of weapons.