In order to tackle organized crime and, in particular, its infiltration and exertion of corrupt influence over legitimate businesses, the United States introduced the offence of racketeering. Racketeering is a newer kind of law with a similar objective to conspiracy and criminal association, but with a broader scope. The offence of racketeering is not included in the Organized Crime Convention. It provides for extended penalties for crimes committed as part of an ongoing criminal enterprise. It is sometimes referred to as RICO for the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, a United States federal law passed in 1970, and makes it unlawful to acquire, operate, or receive income from an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity.

Although only a limited number of Member States have a legislation similar to RICO, several countries have laws with similar intent, but the scope of these laws varies considerably. Australia, Canada, Italy, New Zealand and South Africa are examples with newer laws aimed at racketeering activity such as financial crime, bank transactions, corruption, cybercrime, and other forms of transnational crime. A significant number of racketeering cases involve international organized crime, using the Internet and international exchanges to provide illicit goods and services (Ayling and Broadhurst, 2014; Heber, 2009; Salvador, 2015; Sergi, 2014).

Definition of a racketeering enterprise

An enterprise under RICO is defined as any legal or illegal ongoing business or group that is used as a base for criminal activity. Racketeering activity can be defined broadly, and many felonies suffice for liability, if conducted as part of an enterprise and pattern. An enterprise can be any individual or group (legal or illegal organization) that commits these crimes. The pattern is two or more felonies committed within a 10-year period (excluding any periods of imprisonment of the defendants).

The RICO law attaches extended penalties (up to 20 years of imprisonment) for crimes committed in "racketeering" fashion, that is, specified felonies committed as part of a criminal enterprise and as part of a pattern. These RICO provisions were established to attack organized criminal groups and their operations.

The precise scope and meaning of "enterprise," "pattern," and the activities that suffice for "racketeering activity" have been developed through a series of domestic court decisions and interpretations, as is customary in the common law tradition, and racketeering cases now include corporate misconduct, public corruption, and other ongoing criminal activity. It is the enterprise that lies at the centre of racketeering (Kleemans, 2017; State of New Jersey Commission of Investigation, 2011; Transcrime, 2012; U.S. Department of Justice, 2016).

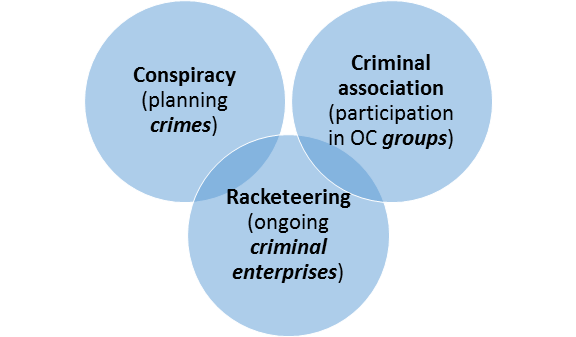

Figure 2.1 illustrates the differences in the three approaches to the criminalization of organized crime. Conspiracy focuses on the planning of criminal acts, criminal association focuses on membership in criminal groups, whereas racketeering focuses on ongoing criminal enterprises.

Racketeering is a tool for the criminal justice system to go after those criminal enterprises that engage in ongoing organized crime activity, rather than only prosecute individuals or groups for specific illegal acts. It was observed more than 80 years ago that "racketeering cannot exist without protection" (Chamberlin, 1932). Criminalization of racketeering aims to remove some of the protection that surrounds criminal enterprises by exposing those involved to extended penalties beyond those entailed by the crimes themselves.

In addition to the offences of conspiracy, criminal association and racketeering, liability needs to be extended to persons who provide advice or assistance in the commission of serious crimes involving organized crime. This liability specifically includes persons intentionally organizing, directing, aiding, abetting, facilitating or counselling the commission of serious crime involving an organized criminal group, as the Organized Crime Convention states. These provisions enable the prosecution of leaders, accomplices, organizers, and arrangers, as well as lower-level participants, in the commission of serious crimes. Aiding, abetting, facilitating or counselling also covers secondary parties and accomplices who are not themselves principal offenders.