To ensure that government agencies are complying with their international obligations to enact effective policies to prevent trafficking, as well as laws to bring traffickers to justice and provide appropriate protection, assistance and support to victims of trafficking, monitoring, evaluation and reporting mechanisms must be developed at both international and national levels.

In 2004, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights appointed a Special Rapporteur to "focus on the human rights aspects of victims of trafficking, especially women and children". The Special Rapporteur was asked to submit an annual report that includes recommendations "on measures required to uphold and protect the human rights of victims". The Special Rapporteur, Maria Grazia Giammarinaro, in her thematic report on the subject of trafficking in persons in conflict and post-conflict situations released on 3 May 2016, made recommendations in the area of prevention.

States are also required to submit reports in compliance with their international obligations according to different international conventions. For instance, article 6 of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) provides that "State Parties shall take all appropriate measures including legislation, to suppress all forms of traffic in women and exploitation of prostitution of women". CEDAW requires State parties to submit, every four years, a report on the legislative, judicial, administrative or other measures they have adopted to implement provisions of the Convention, including article 6.

Similarly, article 35 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) provides that "State Parties shall take all appropriate national, bilateral and multilateral measures to prevent...traffic in children for any purpose or in any form". The CRC requires State Parties to submit, every five years, reports on "the measures they have adopted which give effect to the rights recognized".

In 2018, the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) approved, in Resolution 9/1, the Mechanism for the Review of the Implementation of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols thereto. The review will facilitate the exchange of experiences, lessons learned, good practices, gaps and challenges in implementing UNTOC and its Protocols, including the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons, as well as the identification of technical assistance needs. It will be facilitated by a general report on trends and patterns prepared by the Secretariat before each session of the Conference based on Member States' self-assessment, country reviews and ensuing recommendations, UNODC (as the Secretariat to the Conference of the Parties) will produce a general report on trends and patterns in the implementation of those instruments, including the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons.

In addition to reports submitted to the United Nations, States should prepare national reports to monitor the status of human trafficking and assess government efforts to confront it. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking call upon States to establish "mechanisms to monitor the human rights impact of anti-trafficking laws, policies, programmes and interventions "and further states that "consideration should be given to assigning this role to independent human rights institutions where such bodies exist".

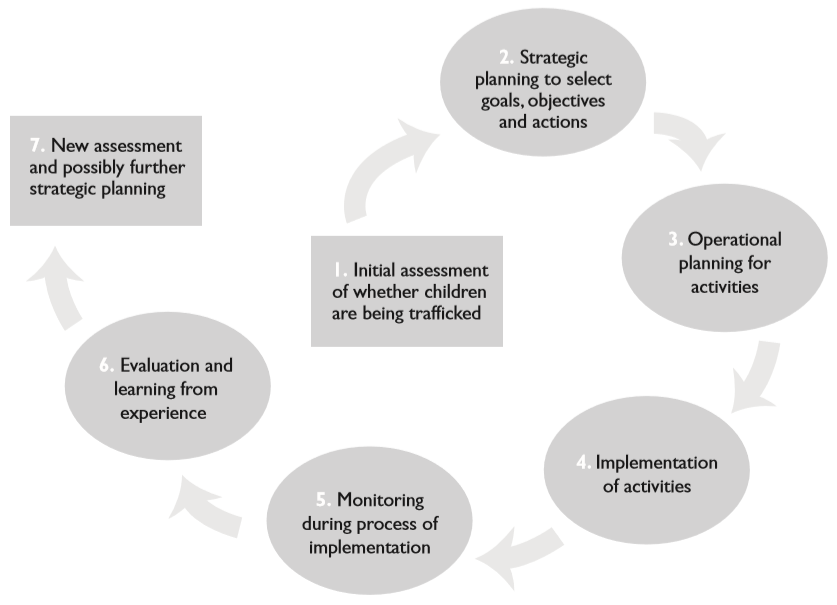

Figure 2 provides a schematic example - focused on child trafficking - of the process of planning and monitoring projects aimed at preventing trafficking.

Many States have established national coordinating committees or inter-ministerial task forces to carry out this function. The Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Persons 2005, in article 29, called upon each State party to consider appointing a national rapporteur or utilizing other mechanisms for monitoring the State's efforts in implementation of their national legislation.

There are different models regarding national structures mandated to address trafficking, provide protection, assistance and support to victims and monitor trafficking activities.

For example, the "National Commission for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings" was established by the Combating Trafficking in Human Beings Act of 2003 of Bulgaria. Article 7 of the Act states:

The National Commission shall:

As to the composition of the National Coordinating Committees, the involvement of NGOs should be imperative. For instance article 10 of the Law on Combating Human Trafficking of 2006 of Georgia provides for the establishment of an "Interagency Coordination Council" and states that "[i]n addition to representatives from state agencies, the Coordination Council may consist of representatives from not-for-profit legal entities and international organizations working in the relevant field, representatives from mass media and relevant specialists and scientists".

In Australia, the response to trafficking in persons is coordinated through the country's National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking and Slavery. As part of its governance and monitoring systems, there is an interdepartmental government committee on human trafficking and slavery, which ensures that issues are addressed in a holistic manner. There is also an Operational Working Group on Human Trafficking and Slavery, comprised of police, prosecution, border protection and social services departments. This working group monitors the Government's strategy and resolves operational issues. In addition, a national roundtable is set up as a consultative mechanism between Government, NGOs, businesses and labour unions, as well as various ad-hoc working groups.

Local, regional and provincial initiatives can also be contemplated. Planning, information, training, awareness-raising, monitoring and coordination between the different participants are critical elements in an effective preventive strategy and respective implementing measures. Equally essential is to provide for periodical assessments to verify whether the strategy is successful, or whether it should be altered, re-considered or replaced.

In Belgium, there are periodic coordination meetings of all actors involved in the fight against human trafficking in each judicial district. At least two such meetings are organised each year on the initiative of the prosecutor specialised in trafficking matters. The aim of these meetings is to:

Partners involved in the cooperation: These meetings are organised and chaired by the key prosecutor for trafficking in human beings cases and attended by Police (specialised trafficking units), Social Inspectorate (specialised units ECOSOC) and Labour Inspectorate. Besides, the prosecutor can invite any experts to these meetings who can make a relevant contribution to investigations or prosecutions (e.g. the Aliens Office, Tax service, shelters, and so on).

What makes this practice successful? These regular meetings create a network which facilitates the exchange of information at the local level, the mapping of high-risk sectors and workplaces and smooth co-operation. Partners get to know and trust each other and become aware of each other's powers and priorities, and that way any thresholds to work together are lowered.

In 2010 the Mazovian Unit against Trafficking in Human Beings was appointed in Warsaw. It was the first and the only regional (voivodship) unit in Poland. The Mazovian Unit was set up as a regional platform for exchange of information and cooperation between institutions and organisations involved in counteracting trafficking in human beings. The unit aimed to improve the organisation of preventive activities, support and reintegration of victims (in particular Polish citizens) and to trigger the activity of local governments and non-governmental organisations in this regard. Apart from that, it also acted as a pilot project in developing regional forms of cooperation in other regions of Poland. One of the major tasks under the National Action Plan against Trafficking in Human Beings for 2013 - 2015 was to initiate more voivodship units against trafficking in human beings in Poland. So far, 14 out of 16 voivodship units have been created. The final two are expected to be appointed by the end of 2015. In each unit a THB [trafficking in human beings] coordinator has been appointed. This TIP coordinator has been obliged to identify partners from various regional stakeholders (local and municipal administration, NGOs, Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) etc).

Partners involved in the cooperation: The units comprise representatives of regional police and border guard forces, local NGOs, regional social assistance units, academic entities, the labour inspectorates, as well as the municipal authorities. The main role of LEAs participating in the units is to provide updated information about the trends and risks related to the crime of THB in the region, as well as to identify and refer the victims to the regional assistance centres for victims. The rest of the participants are mainly engaged either in preventive activities or in supporting the victims.

What makes this practice successful? The voivodship units are regional platforms for exchanging local information mainly about preventing and combating the crime of TIP. Thanks to the unit, the local stakeholders can cooperate among themselves and be more successful in their actions. It is particularly expected when prompt assistance to victims is needed. Apart from that, the units might be helpful in organising regional preventive actions such as local conferences, university lectures and practical classes at schools.

In South Asia 'vigilance committees' have been given a variety of tasks at local level, usually under the leadership of a government-nominated official. In Bangladesh, for example, the Ministry of Home Affairs has created 'anti-trafficking committees' at district, provincial and village level along the country's border with India. Members of these committees are governmental officials and influential members of the community (school head teachers, religious leaders, etc.). They generally coordinate with NGOs involved in trying to prevent trafficking. As the topic of human trafficking has taken a higher profile, more and more structures have been set up, so new members attend numerous training sessions. However, the amounts invested in training and setting up new structures are not rewarded by corresponding results. Unfortunately, members of such committees can easily become responsible for infringing children's rights rather than protecting them, especially if they are not accountable to the central government or to local people in any formal way. Two years after surveillance committees were established in one West African country, Mali, researchers found that surveillance committees did not distinguish between trafficked children and other children leaving their homes to earn money elsewhere: they were aimed at stopping any children from leaving the village. In neighbouring Burkina Faso similar committees acted so enthusiastically and indiscriminately that they even stopped 18-year-old boys (i.e. young adults) from migrating. The researchers in Mali furthermore found that young people were excluded from the committees (i.e. there was no 'child participation'), that the seizure of young people trying to leave the village was causing a crisis in relations between the young and the old, and that young people were resorting to techniques to migrate that made them more vulnerable to abuse. In such circumstances, the surveillance committee system has become part of the problem rather than offering the solution. There are various reasons why efforts to stop trafficking at community level degenerated into bad practice. The principle ones were the failure, from the level of central government (and the international organizations working with them) downwards, to distinguish between cases of trafficking and children travelling in other circumstances and the failure to prepare and train local surveillance committees adequately.