One of the purposes of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons is, under article 2, "to protect and assist the victims of...trafficking, with full respect for their human rights". Articles 6, 7 and 8 set out several provisions related to the protection and assistance of victims. While the Protocol has a criminal justice focus, it is an integral element of a human rights-based approach to trafficking in persons. As Ezeilo (2015, p. 146) notes, "the Protocol has advanced global action to protect and respect human rights of trafficked persons".

For a critical overview of the rescue-rehabilitation-reintegration framework used in trafficking in persons, please see Module 13.

Article 6 of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons outlines the following provisions aimed at protecting and assisting victims of trafficking:

1. In appropriate cases and to the extent possible under its domestic law, each State Party shall protect the privacy and identity of victims of trafficking in persons, including, inter alia, by making legal proceedings relating to such trafficking confidential.

2. Each State Party shall ensure that its domestic legal or administrative system contains measures that provide to victims of trafficking in persons, in appropriate cases:

(a) Information on relevant court and administrative proceedings;

(b) Assistance to enable their views and concerns to be presented and considered at appropriate stages of criminal proceedings against offenders, in a manner not prejudicial to the right of the defence.

3. Each State Party shall consider implementing measures to provide for the physical, psychological and social recovery of victims of trafficking in persons, including, in appropriate cases, in cooperation with non-governmental organizations, other relevant organizations and other elements of civil society, and, in particular, the provision of:

(a) Appropriate housing;

(b) Counselling and information, in particular as regards their legal rights, in a language that the victims of trafficking in persons can understand;

(c) Medical, psychological and material assistance;

(d) Employment, educational and training opportunities.

4. Each State Party shall consider, in applying the provisions of this article, the age, gender and special needs of victims of trafficking in persons, in particular the special needs of children, including appropriate housing, education and care.

5. Each State Party shall endeavour to provide for the physical safety of victims of trafficking in persons while they are within its territory.

6. Each State Party shall ensure that its domestic legal system contains measures that offer victims of trafficking in persons the possibility of obtaining compensation for damages suffered.

Article 6(1) relates to the privacy of victims. This includes their identity not being made public in court judgments or media reports of arrest or criminal proceedings against traffickers. Criminal procedural laws should include provisions giving courts the authority to safeguard the privacy of victims, including by adopting measures to keep aspects of the proceedings confidential. These may be, for instance, the exclusion of members of the public or media when victims are providing evidence, or limitations on the publication of specific information on the victims (such as details that would allow for their identification), including when redacting court judgements ( UNODC, 2006).

States also have an obligation under article 6(2) of the Protocol to ensure that victims can access information about their legal rights and their potential involvement in court proceedings (see also article 6(3)(b)). Victims should ideally be granted legal assistance. The OHCHR Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking insist on "providing trafficked persons with legal and other assistance in relation to any criminal, civil or other actions against traffickers/exploiters". However, this does not necessarily mean formal legal representation in court. An example of a promising practice on this point is reflected below:

Action pour les enfants is a non-governmental organization established to combat the sexual exploitation of children. In addition to social workers who provide counselling and rehabilitation services to child victims, the organization's lawyers provide pro bono legal advice and representation to children and their families. The organization also monitors cases before Cambodian courts, reports on adherence to legal procedures and collaborates with foreign law enforcement and international organizations in education, advocacy and awareness-raising activities. Through the Cambodian Defenders Project (www.cdpcambodia.org), a group of lawyers working in Cambodia assists people through the legal process and to develop the legal system. The Project's Centre Against Trafficking provides legal assistance to victims of trafficking and conducts training for local police authorities in relation to trafficking investigations.

Although not expressed as a right of victims, the Protocol requires States to consider implementing measures for the physical, psychological and social recovery of victims under article 6(3). Immediately following their liberation from traffickers, many victims require the following assistance:

Once these immediate needs are met, additional assistance needs commonly arise, including:

An example of where a lack of adequate assistance measures can have a negative effect on victims is described in the following box.

Poor physical and mental care is putting pregnant trafficking victims in Britain at increased risk of health complications, trauma and extreme poverty, campaigners said on Thursday. Nearly two in three trafficking victims who are pregnant - many as a result of rape - received no antenatal care before their third trimester, and a third had suicidal thoughts during pregnancy, according to a report by Charity Y. "If you've been controlled for most of your life and have lost your sense of agency, then it's incredibly difficult to trust someone and ask for help," said Patrick Ryan, chief executive of Charity Y, in a phone interview.Ryan said health professionals needed help to identify trafficking victims, and those women needed priority access to antenatal care, more financial and housing support, and befriending programs to tackle loneliness. The report is based on the experiences of more than 140 pregnant women who are or have been victims of trafficking in London - 88 percent were forced into prostitution and one in ten were exploited as maids in people's homes. It found that pregnant women did not access health services because they feared reprisals from their traffickers, or because the examinations prompted flashbacks.In one instance a woman's first antenatal appointment was so late that she went into labour during her first scan, it said.Janet Fyle, the College of Midwives' lead on modern slavery, said pregnant trafficking victims were often "traumatized and in extremely poor physical and mental health, even before they reach Britain". "Many are anaemic, have sexually transmitted diseases, wounds or even broken bones as a result of beatings and abuse," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone. Despite repeated efforts, a Home Office spokesman was not available to comment.Between a quarter and half of trafficking victims in Britain are pregnant or have children with them or in their home countries, according to a 2016 report by the Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group.The group's members include Anti-Slavery International, Amnesty International and the United Nations children's agency.At least 13,000 people across Britain are thought to be victims of forced labour, sexual exploitation and domestic servitude, the government has said.However, the police believe the true figure could be in the tens of thousands with slavery operations on the rise.Kate Garbers, managing director of Unseen, an anti-slavery charity, said by email that any assistance would also need to help exploited women deal with the impact of sexual assault.

This can be contrasted with a promising practice in Canada regarding assistance for victims of trafficking. The following also relates to the provision of status and reflection periods for victims (see further below).

The Government of Canada offers various avenues for assisting victims. The temporary residence permit is intended to provide a reflection period for the victim and an investigative window for law enforcement to define whether there is enough evidence to pursue a trafficking case. In June 2007, the Canadian Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration introduced new measures to help assist victims trafficked into Canada. The new measure extends the length of the temporary residence permit for victims to 180 days, up from 120. Depending on individual circumstances, this visa can be renewed at the end of the 180-day period. Victims with a temporary residence permit have access to federally funded emergency medical services, psychological and social counselling and other programmes and services, such as legal assistance. Victims are eligible to apply for assistance from funds maintained by the provincial governments for assistance to victims. Under the new measures announced in June 2007, human trafficking victims are now also able to apply for a work permit to protect them from revictimization. The fees for work permits are waived for holders of this special temporary residence permit. In addition to these measures, and depending on their particular circumstances, there are a number of other avenues that possible victims may pursue. For example, they may apply for permanent residence from within Canada through the refugee determination process, on humanitarian and compassionate grounds or, over time, as members of the permit holder class.

In addition to the measures outlined in article 6(3), States must endeavour to ensure that victims are safe while within their jurisdiction (article 6(5) of the Protocol). The right to safety concerns both instances of harm originating from traffickers and from other individuals. For example, if the State requires a victim to testify against their traffickers, it must consider the need for, and if required, arrange appropriate witness protection measures.

Article 6(6) of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons requires each State party to ensure that its legal system contains measures that offer victims the right to obtain compensation for damage suffered. This is in accordance with international human rights law, in particular article 3(a) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which requires States to "ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy...."

OHCHR's Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking recognize a right to compensation for trafficking victims. Yet, the document also acknowledges its limitations. Guideline 9 states:

"Trafficked persons, as victims of human rights violations, have an international legal right to adequate and appropriate remedies. This right is often not effectively available to trafficked persons as they frequently lack information on the possibilities and processes for obtaining remedies, including compensation, for trafficking and related exploitation. In order to overcome this problem, legal and other material assistance should be provided to trafficked persons to enable them to realize their right to adequate and appropriate remedies".

Payment of compensation to victims improves their prospects of rebuilding their lives by providing them with a source of funds to establish a business, gain an education or training or repay debt. Compensation may include allowances for unpaid wages, legal fees, medical expenses, lost opportunities and compensation for pain and suffering. In some jurisdictions, it may include exemplary or punitive damage to punish an offender for his/her abusive behaviour.

Compensation may be financed by traffickers' confiscated assets. In many jurisdictions, a civil claim for damages can be heard concurrently with a criminal trial and monetary awards are included in court judgements (some of the benefits to civil, tort law claims are analysed in Harvard Law Review Association 2006). Other jurisdictions allow for recovery of damages through civil claims, independent of criminal prosecutions. These include claims for unpaid wages filed in labour courts and contract and tortious claims for unlawful wrongs causing damage filed in civil courts.

In some countries, material support to victims has also been made available through specific State funds. Trust funds for victims have also been established with finances obtained from monetary fines and penalties resulting from criminal convictions. Other countries have given victims of trafficking access to existing general assistance funds, such as those devoted to victims of serious crimes or violence.

However, it should be noted that non-residents may face obstacles accessing compensation because of their status and/or lack of documentation. It can also be more difficult for foreign victims to enforce compensation awards against traffickers, particularly those payable by instalments ( The Bali Process 2015).

An additional, important issue is the fact that, in practice, victims of trafficking will only receive compensation where they understand their legal options for obtaining it. The provision of accurate information and legal advice is fundamental and should be adaptable to the particular situations and circumstances of trafficking a victim has experienced. While the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons does not include a specific obligation to provide victims with such information, article 6(2) - regarding the provision of information to victims (see above) - is relevant. Simmons (2012) discusses some of the issues around providing compensation to victims of trafficking in the Australian context.

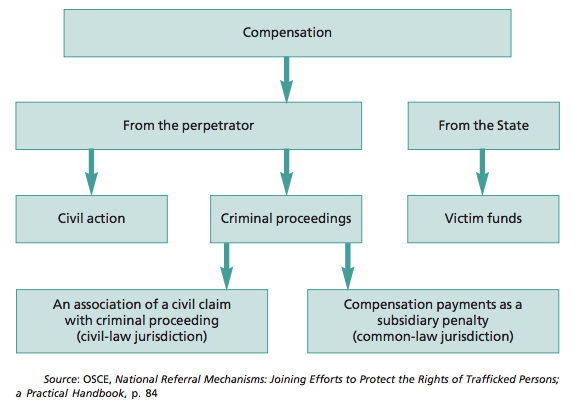

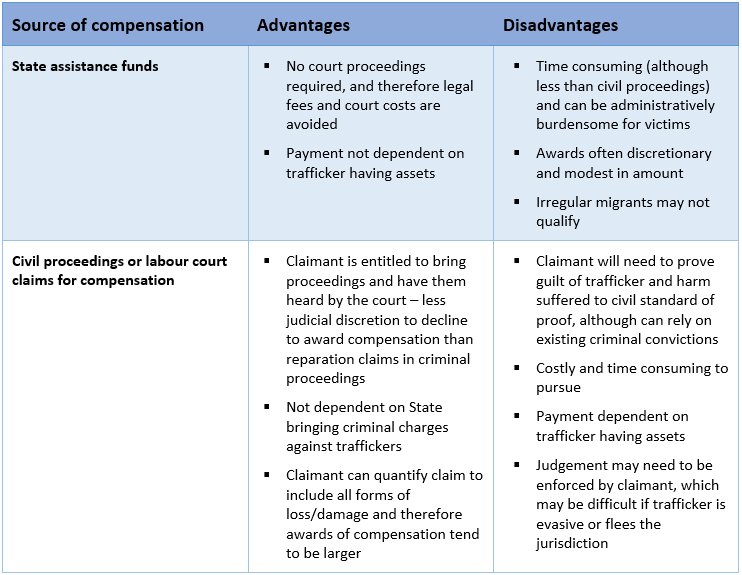

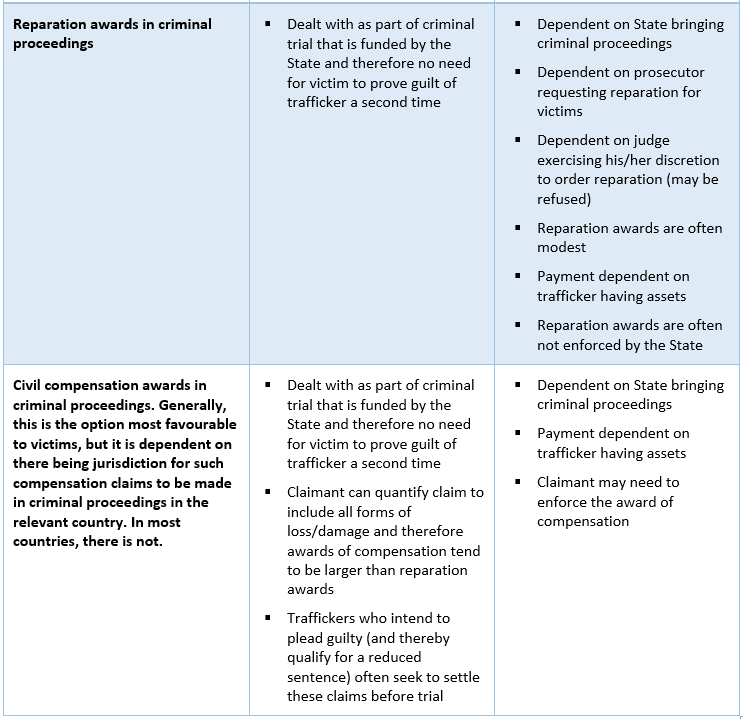

Figure 1 illustrates the possible sources of compensation. The table in Figure 2 reflects the comparative advantages and disadvantages of these alternative sources of compensation.

The 2016 Inter-Agency Coordination Group Against Trafficking in Persons (ICAT) Issue Paper on Providing Effective Remedies for Victims of Trafficking in Persons, lists a number of reasons why compensation regimes for victims often fail in practice:

Another barrier to fair compensation for victims may be the difficulty of accurately assessing the amount of compensation to be granted. In a study of Dutch cases from 2013-14, Cusveller and Kleemans (2018) observe that conflicting or incomplete testimonies, lack of investigation, inadmissibility of certain evidence, were all factors in the awarding of low levels of compensation to victims.

States have developed a range of compensation models to assist victims. Some models entitle victims to issue civil claims for compensation against traffickers, while others deal with compensation entitlements in the context of criminal proceedings against traffickers.

Combating Human Trafficking Law No. 15 of 2011 (Qatar)

Under Qatar law, a civil claim against traffickers for compensation can be heard concurrently with criminal proceedings. Article 10 of the Law No. 15 of 2011 of Qatar on Combating Human Trafficking provides that " The competent court having jurisdiction to consider a criminal action arising from any of the offenses provided in this Law, shall also decide on civil suits arising from such crimes ".

Combating of Trafficking in Persons and Sexual Exploitation of Children Law No. 3 (1) of 2000 (Cyprus)

Article 8 provides that victims of exploitation have a right to special and general damages from their perpetrators. In assessing such damages, courts can consider the extent of exploitation, the benefit the perpetrator derived from the exploitation, the extent to which the future prospects of the victim were adversely affected by having been trafficked, the culpability of the offender and the relationship of the offender with the victim. Special damages can include all costs incurred as a result of the trafficking, including the cost of repatriation.

Anti-Trafficking Law No. 126 of 2008 (Oman)

Article 17 of this Oman law enhances access to justice for victims by exempting them "from the fees of the civil procedures they make to claim compensation for the damage caused by their exploitation in the crime of trafficking in persons".

Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Persons Law No. 61 of 2016 (Tunisia)

According to Chapter 63 of this Tunisian law, victims who receive final verdicts for compensation and are not able to execute them against the perpetrators of the crime may ask to obtain the amount of compensation from the State itself. The State may then subrogate the victims in obtaining these amounts of money.

Victims Support and Rehabilitation Act 1996 (New South Wales, Australia)

The New South Wales Victims Compensation Tribunal was established under the Victims Support and Rehabilitation Act 1996, and consists of magistrates who determine appeals against rulings and make orders for recovery of money from convicted offenders, compensation assessors who make determinations in compensation claims and approve counselling applications, and tribunal staff who provide administrative support in the processing and determination of compensation and counselling claims, appeals and restitution. In May 2007, the Tribunal awarded compensation to a Thai woman who was trafficked to Australia as a child for the purpose of sexual exploitation. (UNODC, Toolkit to Combat Trafficking in Persons, Chapter 8: Victim Assistance (2008))

Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000 (United States)

This United States law requires courts to grant victims of trafficking in persons mandatory restitution for the " full amount of the victim's losses", " in addition to any other civil or criminal penalties authorized by law".

The term "full amount of the victim's losses" includes:

Restitution is calculated based on "the greater of the gross income or value to the defendant of the victim's services or labour or the value of the victim's labour as guaranteed under the minimum wage and overtime guarantees of the Fair Labour Standard Act."

In this model, the confiscated proceeds of the crime of human trafficking are used to provide compensation to the victims and may also be utilized for establishing protective programmes for the victims.

Unlawful Smuggling of Migrants and Trafficking in Persons 2003 (Dominican Republic)

Article 11 of this Dominican Republic law provides that " Proceeds of the fines of the crime of trafficking shall be used to compensate the victims of trafficking for material damages as well as moral damages and to establish the programs and projects of protection and assistance that the law provides for the victims of trafficking".

The Punishment for the Crime of Trafficking in Persons 2011 (Lebanon)

Similarly, article 586.10 of this Lebanese law provides, " Sums of money that are earned from the crimes (of trafficking) shall be confiscated and deposited in a special account with the Ministry of Social Affaires assisting the victims of these crimes".

I come from a village in the Savannakhet province. My family was poor so I had to leave school at grade 5 to help in the rice fields. I heard about a good job in Thailand, which would pay around 75 Euros a month plus food and accommodation. I was desperate to help my family, so I took up the offer. Together with another girl I travelled to Thailand in a service truck. I worked at Mr. P's food shop but I was too slow so had to do housework for him instead. For seven days I laboured at his house. He beat me on the head and torso with a metal ice shovel every day. Or he would use a paddle. His wife would throw chilli in my face, pour cleaning liquid on me or repeatedly immerse my head in hot water. With raw bruises I was forced to work. I had to sleep outdoors on the ground. I was never paid. Eventually, some neighbours took pity on me and helped me to escape. Monks from a temple took me to a hospital. I then spent almost two years in a shelter in Thailand before I was repatriated to Laos in 2014. I was successful in taking legal action against Mrs. P and received 500 Euros in compensation.

In United States v. Sabhnani, 599 F. 3d 215 (2dCir. 2010) , the defendants, a husband and wife, recruited two women from Indonesia to work in their 5,900 square foot house in Long Island, N.Y. The first victim was a 53-year-old, who could not speak English. She was asked to cook, clean, do laundry and other housework for $US200 a month which she never received. Instead, the defendant paid her daughter in Indonesia $100 per month. She worked long hours without proper clothing or adequate sleep. She was constantly beaten and punished and was told that if she wanted to leave, she had to pay for her travel. She was also threatened with police arrest owing to her illegal status. The second victim, who was 47 years old was alas subjected to the same severe and inhuman working conditions and was denied medical care when she was sick or injured. She was told that if she ran away she would be shot by the police. The first victim was able to run away from the defendants' house during their absence and reported her case to the police. The defendants were arrested and were convicted of offences relating to forced labour, harbouring aliens, peonage, and servitude. The first defendant was sentenced to 40 months in prison and the second defendant was sentenced to 132 months in prison. The United States Court of Appeals for the second circuit supported the trial court's decision that victims should receive not only back wages, but also liquidated damages under the Fair Labour Standards Act. After reassessing the hours worked by both victims, the trial court ordered the defendants to pay substantial damages to the victims.

Article 6(4) of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons calls upon States parties to have regard to the special needs of children by requiring them to"take into account, in applying the provisions of this article, the age, gender and special needs of victims of trafficking in persons, in particular the special needs of children, including appropriate housing, education and care". The modification of the definition of trafficking (article 3) - omitting the "means" element - when children are victims should also be noted (see Module 6).

There is a wealth of guidance, at the international level, to assist countries in ensuring full respect for the rights of child victims. Adopted by General Assembly Resolution 40/3 (29 November 1985), the Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime, and the implementation documents thereto, establish the broad principles and implementation strategies applicable to victims. More specific guidance on the protection of child victims is provided in the Guidelines on Justice in Matters involving Child Victims and Witnesses of Crime (the Guidelines), adopted by the Economic and Social Council in resolution 2005/20. These guidelines play a key role in assisting member states to ensure the delivery of effective just responses, for child victims, that protect children's rights pursuant to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). More specifically, the Guidelines set forth good practice with respect to children's right to be treated with dignity and compassion, the right to be protected from discrimination, the right to be informed, the right to be heard and express views and concerns, the right to effective assistance, the right to privacy, the right to be protected from hardship during the justice process, the right to safety, the right to reparation, and the right to special preventive measures. Further advice on the implementation of the Guidelines at the national level is presented in the Handbook for Professionals and Policymakers on Justice in matters involving child victims and witnesses of crime. This handbook presents good practices relating to the prevention of child trafficking, and sensitive justice responses to victims, including: children's right to privacy; the automatic use of closed hearings in cases of child trafficking; the importance of preventing the intimidation of child victims of trafficking; and the importance of specialised training for criminal justice personnel.

OHCHR's Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking provide guidance on how to respond to children who are identified as victims. Guideline 8 calls upon States to consider the following issues:

The particular physical, psychological and psychosocial harm suffered by trafficked children and their increased vulnerability to exploitation require that they be dealt with separately from adult trafficked persons in terms of laws, policies, programmes and interventions. The best interests of the child must be a primary consideration in all actions concerning trafficked children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies. Child victims of trafficking should be provided with appropriate assistance and protection and full account should be taken of their special rights and needs.

States and, where applicable, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations, should consider, in addition to the measures outlined under Guideline 6:

Some States have enacted legislation focusing on child rights and protection. Others have done so in a statute specifically directed at trafficking in persons. Two examples of the former are provided below.

The Children's Act of 2009 of Botswana, in article 114, provides that " Any person, including a parent, other relative or guardian of a child, who abducts or sell any child, traffics in children or uses any child to beg, shall be guilty of an offense..."

Child Law of Egypt No. 12 of 1996 as amended by the Law No. 126 of 2008, stipulates that " It is prohibited to violate the right of the child to protection from trafficking or from sexual, commercial or economic exploitation, or from being used in research and scientific experiments, the child shall have the right to awareness and be empowered to address those risks".

States parties to the CRC are required to "take all appropriate national, bilateral and multilateral measures to prevent the abduction of, the sale of or traffic in children for any purpose or in any form" (article 35). Additional international conventions and protocols call for the criminalisation of child trafficking, with States parties to the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography and the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children obligated to prevent, investigate and punish the perpetrators of these crimes. The United Nations Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence Against Children in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (the Model Strategies) provide Member States with further guidance on integrated strategies for protecting children from violence. The Model Strategies affirm the importance of comprehensive and effective laws to prohibit violence against children, including "[t]he sale or trafficking in children for any purpose and in any form" (para 11 (d)). Furthermore, the Model Strategies recognise the "complementary roles of the justice system on the one hand, and the child protection, social welfare, health and education sectors on the other", offering specific guidance on the development of specialised preventive measures to address the risks of trafficking in children and the sale of children.

Article 7 addresses the "status of victims of trafficking in persons in receiving States":

While not creating a right to residency, article 7 of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons requires States parties to consider adopting legislative or other measures to permit victims to remain in its territory, temporarily or permanently, in appropriate cases, considering humanitarian and compassionate factors.

Victims' immediate return to their home countries may be unproductive both for victims and for authorities involved in the prosecution of traffickers. In the case of victims, their return may lead to reprisals against them or their families at the hands of the trafficker. For law enforcement purposes, if victims are deported, it is unlikely they will be willing or available to testify in court. The more confident victims are that their rights and interests will be protected, the more likely they will choose to cooperate with police and prosecutors ( Inter-Parliamentary Union and UNODC 2009). Stoyanova (2013, p. 278) observes that temporary status has the effect of balancing victims' protection needs and the host States' immigration policies.

It should be noted that, in some cases, victims may gain a separate right against removal under international human rights or refugee law (see further below).

Article 8 addresses the "repatriation of victims of trafficking in persons":

Article 8 of the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons provides that the country of which a victim is a national or permanent resident at the time they were trafficked to a second country, must facilitate and accept the return of the victim without undue or unreasonable delay. In doing so, they must have due regard for the safety of that person and provide any necessary travel documents, such as replacement passports.

Victims have the right to a dignified and safe return to their country of origin. Article 8(2) expresses a preference that the return be voluntary, although in most cases the choices are limited: return by your own means or be returned by the State. Immigration authorities are obliged to ensure victims are protected from past and potential traffickers, both while they are in transit and during their reintegration ( Inter-Parliamentary Union and UNODC 2009). As Schloenhardt and Loong note (2011, p. 144), "[t]he proper observance of appropriate rehabilitation and reintegration mechanisms guarantees, in general terms, the long-term safety and wellbeing of victims and their community whilst simultaneously re-securing human rights and safeguarding against re-victimization, reprisal or retaliation".

The Act provides that the Secretary of State and the Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development, in consultation with appropriate non-governmental organizations, are to establish and carry out programmes and initiatives in foreign States to assist in the safe integration, reintegration or resettlement, as appropriate, of victims of trafficking. Appropriate steps are also to be taken to enhance cooperative efforts among foreign countries, including States of origin. Funding is provided either to States directly or through appropriate non-governmental organizations for programmes, projects and initiatives. This includes the creation and maintenance of facilities, programmes, projects and activities for the protection of victims. These principles provide a clear basis for a return and reintegration system that safeguards the human rights of trafficking victims to a safe return and assistance towards reintegration in the State of origin. Following these principles, programmes should offer a broad variety of services tailored to the individual needs of the returnee, such as pre- and post-departure counselling, financial support, integration assistance, follow-up and referral assistance, family mediation, continuing education, opportunities for self-support and job-seeking within the State of origin. This is important for the survival and well-being of the returned victim of trafficking and as a factor in preventing the victim from being trafficked again.

Victims of trafficking are seldom granted permanent residence status on humanitarian grounds and, eventually, most trafficked victims must return to their State of origin or move to another State. Many of these victims need help in returning home. IOM is one of the resources available to assist victims in the pre-departure, departure, reception and integration stages of the rehabilitation process. In countries of origin and destination, IOM offers immediate protection in reception centres in collaboration with local non-governmental organizations. Health-care facilities at rehabilitation centres provide psychological support, as well as general and specialized health services. In accordance with local laws, IOM provides voluntary and dignified return assistance to victims of trafficking. Such assistance includes counselling, education and vocational training for income-generating activities in countries of origin in order to reduce the risk of revictimization.

The Bangladesh National Women's Lawyers' Association offers legal support to women and children victims of trafficking. The Association has 28 legal clinics in different districts and 13 focal sites in 13 trafficking-prone areas. In addition, it has shelters in Dhaka where survivors of trafficking (as well as violence and discrimination) are helped to become reintegrated into society by means of job placements or to be repatriated to their country of origin. The Association focuses on the rehabilitation of victims of trafficking and is campaigning particularly to strengthen action against trafficking of children to Gulf States for use as camel jockeys. It has successfully repatriated several victims of this crime from India, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates in collaboration with the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. After victims are repatriated, the Association provides treatment and counselling and other services to returnees and takes legal action against traffickers.

The Little Rose Shelter seeks to contribute to the development of an effective and sustainable model for the rehabilitation and reintegration of trafficked girls who have returned to Vietnam from Cambodia. The shelter provides the girls with vocational training to enable them to find a job after a four-month rehabilitation period. If the girls need a longer rehabilitation period, this can be provided. Besides vocational training, the girls in the shelter are provided with courses about life skills, child rights training, literacy classes, health-care services and counselling. Each group of returned victims from Cambodia consists of 15 girls. They have several opportunities to exchange information about their experiences, which is a good method to help them deal with their trauma. All girls who complete the four-month residency at the shelter receive a reintegration grant. The Women's Union, the main counterpart of IOM in this project, coordinates the reintegration of the children into their communities in cooperation with a local committee for population, family and children.

Importantly, nothing in the Protocol precludes the operation of other rights and obligations relevant to victims of trafficking under international law. A savings clause in article 14 of the Protocol makes clear that rights in international humanitarian law, international human rights law and international refugee law instruments apply to victims. The framework of protection set out across these various instruments forms the basis of a human rights-based approach for victims of trafficking. As Gallagher (2009, p. 791) notes, following its creation the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons proved "to be only the first step in the development of a comprehensive international legal framework comprising regional treaties, abundant interpretive guidance, a range of policy instruments, and a canon of state practice" (the article itself responds to a number of criticisms of the Protocol by Hathaway (2008)). Some of this broader framework is summarized in the following section of this Module.

" Nothing in this Protocol shall affect the rights, obligations and responsibilities of States and individuals under international law, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law and in particular, where applicable, the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees and the principle of non-refoulment as contained therein".