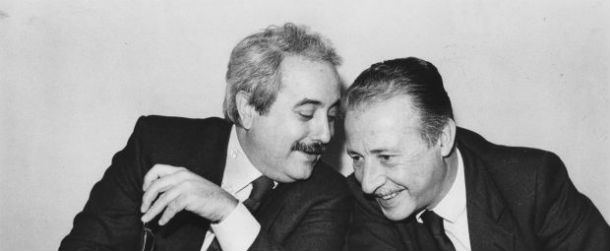

The anti-Mafia judge, Giovanni Falcone, received an iconic status during his outstanding career that ended on 23 May 1992, when he, along with his wife and three bodyguards, was killed by a bomb hidden on the highway leading to the airport of Palermo. It is alleged that criminal boss Toto Riina gave the assassination orders, in revenge for Falcone's success in bringing hundreds of mobsters to court in the maxi-trial ( maxiprocesso) that lasted between February 1986 and January 1992. In addition, Falcone had been one of forces behind the adoption of the first witness protection law of Italy (later amended), which remains to this day one of the most useful weapons against the Mafia, as hundreds of informers (pentiti) agreed to testify in court against mafia bosses. Falcone's murder, and that of his fellow magistrate Paolo Borsellino two months later, led to the creation of the Direzione Investigativa Anti-Mafia (DIA).

One of the highlights of Falcone's career was convincing Tommaso Buscetta to come to Sicily from Brazil to testify at the Palermo Maxi Trial and later at the Pizza Connection Trial in the United States. Buscetta's testimony led to the convictions of more than 300 mafiosi and their associates.

In his speech on 6 May 2016, UNODC Chief Yuri Fedotov also acknowledged the great contribution of Judge Falcone to the fight against organized crime, "whose life and work have inspired and informed the means we still use to carry on his commitment. (…) And that is why it is no exaggeration to talk about the legacy of Giovanni Falcone when we talk about the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, known as the Palermo Convention. He was among the first to recognize the need for an international treaty against transnational organized crime. In April 1992, Mr. Falcone was part of the Italian delegation to the very first meeting of the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, established by the General Assembly, which was 'alarmed by the high cost of crime…especially in its new and transnational forms.' Just one month after this inaugural session, Giovanni Falcone was killed at the hands of the mafia." (Yury Fedotov, UNOV Director General / UNODC Executive Director. Remarks on the Palermo Convention against transnational organized crime: the legacy of Giovanni Falcone. Vienna, 2016.)

On 19 June 2017, pursuant this United Nations General Assembly Resolution 71/209 the President of the General Assembly, in cooperation with UNODC and with the involvement of relevant stakeholders held a high-level debate to observe the twenty-fifth anniversary of the assassination of Judge Giovanni Falcone, focusing on the implementation of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Palermo Convention) and the Protocols thereto and highlighting emerging trends and challenges in crime prevention and criminal justice and their impact on sustainable development. The opening of the day featured remarks by the President of the General Assembly, the Secretary-General, the Chair of the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, the Chair of the Conference of Parties of the Convention, and the Executive-Director of UNODC. There was also a brief ceremony in remembrance of Judge Falcone. Maria Falcone, Judge Falcone's sister and President of the Giovanni e Francesca Falcone Foundation, attended the ceremony.

Regional perspective: Eastern and Southern AfricaCase study 2 (Interpretation of domestic law guided by UNTOC- Namibia)In State v Henock and Others (2019), the High Court of Namibia described the circumstances that gave rise to the birth of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act 29 of 2004 (POCA) in the Namibian context. The Court stated: [6] The existence of international organised syndicates is real and their activities are primarily aimed at the accumulation of wealth through illegal means, such as human trafficking, drugs, poaching, fraud etc. In order to benefit from their illegal activities and avoid prosecution, syndicates would endeavor to hide the illicit origin of their assets, being the proceeds of crime. These assets may then be used to finance further criminal operations. If left unchecked money-laundering could facilitate illegal activities at the expense of countries’ development. Furthermore, because of the result of technological advancements and globalisation, syndicates have discovered ways and means to transfer assets from one place to another and across borders. The crime of money-laundering is thus an international problem which called for an international solution. The Court elaborated on the interpretation of domestic statutes derived from international agreements like the Organized Crime Convention, signed by Namibia on December 23, 2000, and ratified on August 16, 2002. In the view of the Court: [...] courts, when interpreting statutes, should endeavor to interpret those statutes in conformity with international law. Furthermore, […] there is a presumption that Parliament, in enacting a statute, intended it to be in agreement with international law. To this end, the Legislative Guides drafted by the United Nations office on Drugs and Crime Division for Treaty Affairs assist in the interpretation of those provisions. When interpreting domesticated laws, it is imperative to look at the legislative guides, especially where the domesticated law is silent on a certain aspect. In the Henock judgment, the Court reviewed nine cases to clarify the issue of duplication of convictions under POCA. In each of those cases, people had been convicted and sentenced for offences having the nature of theft (predicate offence), except for one where the predicate offence was receiving stolen property, and for contravening either sections 4 (i.e. disguising unlawful origin of property) or 6 of POCA (i.e. acquisition, possession or use of proceeds of unlawful activities). The Court looked at the definition of ‘serious crime’ included in the Organized Crime Convention to conclude that POCA’s severity of punishment implies that the Namibian legislature intended to criminalize the offence of money-laundering also for serious predicate offences, as opposed to offences that are of less serious nature. However, in the absence of legislation establishing which predicate offences are serious, the Court highlighted that prosecution under POCA lies within the discretion of the Prosecutor-General. This discretion must be exercised judiciously and should be guided by POCA’s provisions and binding international agreements. The judgment further clarified the application of sections 4 and 6 of POCA. It held that the author of the predicate offence can equally commit money-laundering when he/she commits any further act in connection with property being the proceeds of unlawful activities (section 4). On the other hand, section 6 only applies to a person other than the author of the predicate offence. Also, since the elements of the offence created under section 6 are similar to the elements of theft, the Court held that convicting for both theft and the contravention of section 6 would amount to a duplication of convictions. Case-related files

Significant features

Discussion questions

Exercise 1Read the scenarios drafted below (based on the cases reviewed by the High Court of Namibia in State v Henock and Others). For this exercise, divide the students in groups and assign a case and a role to each group: taking into consideration the High Court’s judgment, they should either argue in favor or against the ruling from the perspective of a prosecutor and a defendant’s lawyer in each scenario.

Mr. Doe was charged and convicted with the offences of housebreaking, theft, and money-laundering (section 6, POCA).

Ms. Terius was charged with theft and money laundering (section 6, POCA).

The three were charged with theft and money laundering (section 4, POCA). |