The Organized Crime Convention and its Protocols, together with the United Nations Convention against Corruption, are the main international legal instruments in the fight against organized crime and related corruption. The Convention against Corruption entered into force in December 2005. While the Organized Crime Convention requires States parties to criminalize corruption within the framework of organized crime, the Convention against Corruption specifies and recognizes different forms of corruption, and it provides a legal framework for criminalizing and combatting corruption. The Convention against corruption "is the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument."

The Convention against Corruption deals with corruption through a comprehensive set of provisions grouped in four chapters: prevention, criminalization, international cooperation and asset recovery (UNODC, 2012). Corruption is a very complex issue that can be dealt with only through a comprehensive approach. The four pillars of the Convention against Corruption are highly interdependent. For example, an approach centred entirely on reinforcing law enforcement responses would inevitably fail because it would overlook the importance of an adequate system of prevention, as well as the State responsibility to deal properly with the recovery of ill-gotten assets. Similarly, without a proper system of international cooperation in place, prosecution, adjudication and recovery of criminal assets would be unworkable, considering the transnational nature of economic crimes in general, and corruption in particular.

The Convention thus requires States parties to introduce effective policies aimed at preventing corruption. Preventive measures were included with the objective of providing measures involving both the private and public sector. These measures range from institutional arrangements, such as the establishment of a specific anti-corruption body, to codes of conduct and policies promoting good governance, the rule of law, transparency and accountability. The Convention also underlines the importance of involving society as a whole in the fight against corruption and invites each State party to actively encourage the involvement of nongovernmental organizations and foster community initiatives in this sector.

Similarly to the Organized Crime Convention, the Convention against Corruption goes on to require States parties to introduce criminal and other offences to cover a wide range of acts of corruption. In particular, the crimes covered include bribery, embezzlement and illicit enrichment. In addition, acts carried out in support of corruption are also included (obstruction of justice, trading in influence and the concealment or laundering of the proceeds of corruption). Significantly, the Convention against Corruption also deals with corruption in the private sector and provides for the protection of reporting persons (whistle-blowers), witnesses, victims and experts. The section on international cooperation contains provisions very similar to the Organized Crime Convention, including mutual legal assistance, extradition, and confiscation and seizure.

The purpose of the two international instruments is one and the same: enabling States to enhance their international cooperation mechanisms, and thus providing them with legal and operational tools to strengthen their capacity of addressing corruption and organized crime at international level. Nonetheless, in contrast to the Organized Crime Convention and other previous treaties, the Convention against Corruption also provides for mutual legal assistance in the absence of dual criminality, when such assistance does not involve coercive measures. The Convention against Corruption also emphasizes that every aspect of anti-corruption efforts necessitates international cooperation and puts a premium on exploring all possible ways to foster cooperation (article 43). The chapter on international cooperation is central in the Convention against Corruption and, like in the Organized Crime Convention, its articles are among the most complex of the entire Convention.

Finally, the most significant innovation and a "fundamental principle of the Convention" (article 51) is the recovery and return of assets. This chapter aims at creating a comprehensive framework that enables States to address the main objective of economic (as well as organized) crime: obtaining financial benefits. This part of the Convention specifies how cooperation and assistance will be rendered, how proceeds of corruption are to be returned to a requesting State and how the interests of other victims or legitimate owners are to be considered. The correct implementation of this chapter creates the conditions to recover ill-gotten assets from criminals and criminal groups.

|

"Corruption is an insidious plague that has a wide range of corrosive effects on societies. It undermines democracy and the rule of law, leads to violations of human rights, distorts markets, erodes the quality of life and allows organized crime, terrorism and other threats to human security to flourish" (UNODC, 2005). - Secretary-General Kofi Annan |

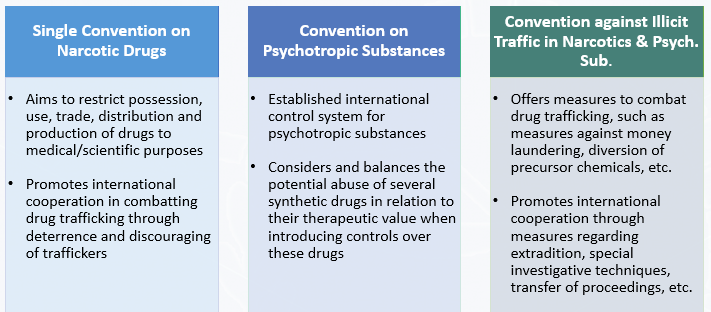

The three major drug control treaties are:

United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988

These three Conventions are mutually supportive and complementary. The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961, as amended in 1972) merged all pre-existing multilateral treaties. Prior to the Single Convention, there had been a number of treaties dealing with international drug control, beginning in 1912 with the International Opium Convention. By enacting the Single Convention, States sought to streamline drug control by establishing the International Narcotics Control Board, replacing pre-existing supervisory bodies. The Convention's aim was to assure adequate supplies of narcotic drugs for medical and scientific purposes, while also preventing diversion into the illicit market. At its heart, the Single Convention limits use and possession of opiates, cannabis and cocaine, to medicinal and scientific purposes. The Convention also creates a classification system that divides drugs into four schedules, establishing differing degrees of regulation for each schedule. The Single Convention exercises control over more than 130 narcotic drugs (the updated Yellow List of internationally controlled narcotic drugs is available on the website of the International Narcotics Control Board - INCB).

The Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971) extended the international drug control system to include hallucinogens, stimulants, and sedatives, such as LSD, amphetamines, and barbiturates and was enacted after an upsurge of drug use in the 1960s. The United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (1988) extends the control regime to precursor substances frequently used in the manufacture of illicit drugs (i.e., drug precursors), focuses on the growing problem of international trafficking and strengthens the framework of international cooperation in criminal matters, including extradition and mutual legal assistance. Please, see Module 3 for more information on drug production and trafficking.

Drug trafficking plays a major role in organized criminal activities, so it is necessary to take into account these drug treaties with the Organized Crime Convention. Though they precede the Convention by several decades, they were designed to accomplish similar purposes, such as combating illicit activities which benefit organized crime, and they include similar provisions to reach this objective (e.g., anti-money laundering provisions). Furthermore, the drug control treaties much like the Organized Crime Convention stress the importance of international cooperation in these endeavours.