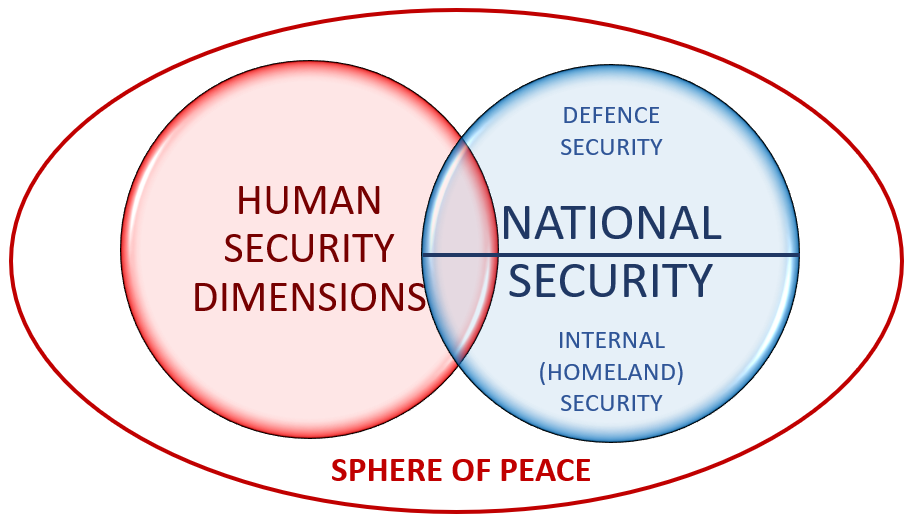

The human security approach broadens the scope of security analysis and policy from the traditional notion of national security to the security of people and their complex social and economic interactions (see also UNDP, 2013). As noted in United Nations General Assembly resolution 66/290, "human security is an approach to assist Member States in identifying and addressing widespread and cross-cutting challenges to the survival, livelihood and dignity of their people". It calls for "people-centred, comprehensive, context-specific and prevention-oriented responses that strengthen the protection and empowerment of all people".

Indeed, human security, among other dimensions, involves the personal security of individuals, understood as safety against threats of crime, violence, war and abuse (see below).

UN GA Resolution A/RES/66/290 on the Follow-up to paragraph 143 on human security of the 2005 World Summit Outcome3. (…) A collective understanding on the notion of human security includes the following: (a) The right of people to live in freedom and dignity, free from poverty and despair. All individuals, in particular vulnerable people, are entitled to freedom from fear and freedom from want, with an equal opportunity to enjoy all their rights and fully develop their human potential; (b) Human security calls for people-centred, comprehensive, context-specific and prevention-oriented responses that strengthen the protection and empowerment of all people and all communities; (c) Human security recognizes the interlinkages between peace, development and human rights, and equally considers civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights; (d) The notion of human security is distinct from the responsibility to protect and its implementation; (e) Human security does not entail the threat or the use of force or coercive measures. Human security does not replace State security; (f) Human security is based on national ownership. Since the political, economic, social and cultural conditions for human security vary significantly across and within countries, and at different points in time, human security strengthens national solutions which are compatible with local realities; (g) Governments retain the primary role and responsibility for ensuring the survival, livelihood and dignity of their citizens. The role of the international community is to complement and provide the necessary support to Governments, upon their request, to strengthen their capacity to respond to current and emerging threats. Human security requires greater collaboration and partnership among Governments, international and regional organizations and civil society; (h) Human security must be implemented with full respect for the purposes and principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, including full respect for the sovereignty of States, territorial integrity and non-interference in matters that are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of States. Human security does not entail additional legal obligations on the part of States; (…) |

GA Resolution 66/290 stresses the role of "[m]ember States in identifying and addressing widespread and cross-cutting challenges to survival, livelihood and dignity of their people". Previously, the 1994 Global Human Development Report had specified that human security includes seven essential dimensions: (i) economic, (ii) food, (iii) health, (iv) environmental, (v) personal, (vi) community and (vii) political. However, this list is neither comprehensive nor definitive.

Several other concepts have progressively been included within the concept of human security, such as social exclusion, modernization and climate change. No matter which topic is addressed, a guiding principle of the human security approach is that it requires understanding of the threats experienced by particular groups of people, as well as the participation of those people in the analysis process. Threats to human security can exist at all levels of development. They can emerge slowly and silently or appear suddenly and dramatically. Central to the approach is the idea that people have the right to live in freedom and dignity, free from poverty and despair, with an equal opportunity to enjoy all their rights and fully develop their human potential.

Human security:

Considering the above, lecturers are encouraged to facilitate a discussion on how the concept of human security could be integrated in the overall debate on the prevention of and fight against smuggling of migrants.

As explained in Module 2, while States are bound to respect and promote human rights (including those of smuggled migrants), in practice this does not always occur. Smuggling of migrants is often understood solely as a threat to States' sovereignty. In the assessment of State security and human security, priority is often given to the former. Yet, underestimating the latter is a major factor in the failure of State policies to effectively counter migrant smuggling.

As long as individuals feel threatened, endangered and persecuted, are subject to widespread violence and are victims of political or social unrest and economic crisis, it is unlikely that people will cease trying to find safety and security abroad, including by using the services of migrant smugglers. These matters must be addressed in both origin and destination countries. Given that a central cause of migrant smuggling is a lack of regular avenues for migration, developing sufficient and responsible alternatives to irregular migration is key. This is especially important, bearing in mind the dangers smuggled migrants are often exposed to during smuggling ventures.

It is notable that social and economic development efforts aimed at addressing root causes of migration, developing avenues for regular and safe migration and/or directly tackling migrant smuggling are often linked to political engagement and frameworks. Some examples of international political processes and commitments follow:

Khartoum ProcessThe Khartoum Process is a platform for political cooperation amongst the countries along the migration route between the Horn of Africa and Europe. Also known as the EU-Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative, the inter-continental consultation framework aims at:

The following countries are signatories of the Declaration of the Ministerial Conference of the Khartoum Process, also known as the Rome Declaration: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Somalia, South Sudan, Spain, Sudan, Sweden, Tunisia and United Kingdom. Since this Declaration, Libya was also invited as a Member of the Khartoum Process upon the establishment of a Government of National Accord, and Norway, Switzerland and Uganda have also become Members of the Process. Khartoum Process |

The AU-Horn of Africa Initiative on Human Trafficking and Smuggling of MigrantsThe African Union - Horn of Africa Initiative on Human Trafficking and Smuggling of Migrants was launched through the Khartoum Declaration of 16 October 2014. It aims at undertaking measures to address human trafficking, migrant smuggling and the numerous factors that make people vulnerable to those crimes, as well as mainstreaming prevention, strengthening law enforcement capacity to respond to the crimes, and fostering cooperation and coordination among all stakeholders. Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Libya, Sudan, South Sudan and Tunisia have endorsed this Initiative. AU-Horn of Africa Initiative |

Rabat ProcessThe Rabat Process is a platform for political cooperation amongst the countries along the migration route between Central, Western, Northern Africa and Europe. It brings together more than 60 partners to openly discuss migration and development questions in a spirit of partnership. Since 2006, the Process promotes policymaking on migration issues, through an approach that includes the link between migration and development. The need to link the countries of origin, transit and destination affected by the western migration routes arose from the acknowledgement that finding a response to the increasing number of migrants wishing to reach Europe by crossing the Straits of Gibraltar or reaching the Canary Islands at the time, was not exclusively the responsibility of Morocco and Spain. A balancing point was sought between the countries which consider development to be a priority to reduce migration flows and those which see the fight against irregular migration as a priority. In this context, France, Morocco, Senegal and Spain took the initiative to establish the Rabat Process in 2006. The Rabat Process |

Bali ProcessSince its inception in 2002, the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime (Bali Process) has effectively raised regional awareness of the consequences of people smuggling, trafficking in persons and related transnational crime. It is a forum for policy dialogue, information sharing and practical cooperation to help the region address these challenges. The Bali Process, co-chaired by Indonesia and Australia, has more than 48 members, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC), as well as a number of observer countries and international agencies. It also includes the Ad Hoc Group, bringing together those most-affected member countries, and relevant international organizations, to address specific people smuggling, trafficking in persons, and irregular migration issues in the region. At the Sixth Bali Process Ministerial Conference (March 2016), Ministers confirmed the core objectives and priorities of the Bali Process through the endorsement of the Bali Process Declaration on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime. The Declaration acknowledges the growing scale and complexity of irregular migration challenges both within and outside the Asia Pacific region and supports measures that would contribute to comprehensive long-term strategies addressing the crimes of people smuggling and human trafficking as well as reducing migrant exploitation by expanding safe, legal and affordable migration pathways. The Bali Process |

New York Declaration for Refugees and MigrantsThe New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, adopted in September 2016 by the General Assembly, expresses the political will of world leaders to save lives, protect rights and share responsibility on a global scale. It includes commitments such as:

United Nations, Refugees and Migrants |

Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular MigrationThe global compact for migration will be the first, intergovernmentally negotiated agreement, prepared under the auspices of the United Nations, to cover all dimensions of international migration in a holistic and comprehensive manner. In the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, the General Assembly decided to develop a global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration. The process to develop this global compact for migration started in April 2017. The General Assembly held an intergovernmental conference on international migration on 10-11 December 2018 in Marrakech and adopted Global Compact for safe, orderly and regular Migration, outlining a framework to better manage international migration. The global compact is a significant opportunity to improve the governance on migration, to address the challenges associated with today's migration, and to strengthen the contribution of migrants and migration to sustainable development. United Nations, Refugees and Migrants |

The following example focuses on military cooperation. However, since it relies on political commitments and agreements between States, it is referred herein under the auspice of 'political responses' to smuggling of migrants.

EUNAVFOR MED - Operation SophiaEUNAVFOR is a EU naval operation mandated by the UN Security Council to disrupt the business model of smugglers and traffickers in the Southern Central Mediterranean (UNSC, Resolution 2240 adopted in 2015). EUNAVFOR MED operation Sophia is but one element of a broader EU comprehensive response to the migration issue, which seeks to address not only its physical component, but also its root causes as well including conflict, poverty, climate change and persecution. The mission core mandate is to undertake systematic efforts to identify, capture and dispose of vessels and enabling assets used or suspected of being used by migrant smugglers or traffickers, to contribute to wider EU efforts to disrupt the business model of human smuggling and trafficking networks in the Southern Central Mediterranean and prevent the further loss of life at sea. Since 7 October 2015, as agreed by the EU Ambassadors within the Security Committee on 28 September, the operation moved to phase 2 International Waters, which entails boarding, search, seizure and diversion, on the high seas, of vessels suspected of being used for human smuggling or trafficking. Last 20 June 2016, the Council extended until 27 July 2017 Operation Sophia's mandate reinforcing it by adding two supporting tasks:

On 30 August and on 6 September 2016, it was authorised the commencement of the capacity building and training and the commencement of the contributing to the implementation of the UN arms embargo. EUNAVFOR MED operation Sophia is designed around 4 phases:

The European Council is responsible for assessing whether the conditions for transition between the operation phases have been met. On the legal side, all of the activities undertaken in each phase adhere to and respect international law, including human rights, humanitarian and refugee law and the "non-refoulment" principle meaning that no rescued persons can be disembarked in a third country. EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia |