The root causes of trafficking are numerous, interconnected and often complex. Broadly speaking, they create the circumstances in which trafficking can flourish. Factors that increase individuals' vulnerability, that increase demand for trafficked persons, their labour and services, and that erode States' capacity to prevent and combat trafficking, are all root causes of the crime (see Gallagher, 2010, chapter 8). In a geographical sense, they may be specific to a particular country or region, or common to trafficking flows in general.

Some root causes of trafficking, such as poverty and a lack of legal avenues for migration, overlap with the drivers of irregular migration and smuggling of migrants (see Module 5). In this context, migrants are vulnerable to the promises of traffickers offering them work or safety abroad, and to exploitation during the irregular migration process itself. Where circumstances lead to the displacement of people and force them into irregular migration, removing them from the protection of their families, communities or government, this can make them even more desperate and vulnerable to traffickers. Armed conflict, persecution and natural disasters can all increase the incidence of trafficking in persons.

Other root causes are tied to individuals' particular characteristics and circumstances. For example, racial, ethnic and gender-based discrimination can deprive people of resources and opportunities, rendering them more susceptible to trafficking. Children's age and lower level of agency can also make them more vulnerable. These factors impact on persons in their communities, as well as during and following migration.

The diversity and complexity of root causes means that it is not possible to enumerate and explain them comprehensively in this Module. Rather, this section sets out and briefly describes seven common causes, including:

These are discussed in the paragraphs that follow.

Poverty and economic vulnerability are primary contributors to trafficking in persons. Economic vulnerability includes unemployment and lack of access to equal opportunities. These conditions induce people to migrate in search of better living conditions. Flows of economic migrants travelling through legal avenues can provide opportunities for traffickers to victimize migrants who, having left the protection of their communities, are vulnerable to exploitation (The Protection Project, 2013). For example, in a 2014 article, Bélanger describes how trafficking can become embedded in legal temporary migration flows, with exploitation manifesting in the recruitment of bonded labour. In general, poorer and lower-skilled individuals are more susceptible to false promises of work and pay from traffickers, who may deceive and coerce them into situations of trafficking (Wheaton, Schauer and Galli, 2010, pp. 121-122; Kara, 2011, p. 67-68).

I walk along the streets in Olongapo city where scantily clad women pose outside entertainment clubs and beckon passers-by to come inside for a "good time". I enter one of the "videoke bars" and find myself in a dimly lit den where foreign businessmen and locals watch inebriated women gyrate on a stage. From the bar, I watch a Westerner buy another drink from a young Filipina whose language he does not speak. If the man wants to buy her for sex, he will pay the bar owner a fee called a "bar fine". Looking at this young girl, I wonder how she ended up here. I wonder if she will take her customer to a back room in the bar or to her home and risk waking up any children she might have. I wonder if she's ever been beaten or raped by her customers. Or, if she ever had to contact a "hilot" (midwife) who terminates unwanted pregnancies by violently pounding a woman's stomach until she miscarries. When the customer leaves to use the bathroom, I approach the girl who looks surprised and a little annoyed that I've intruded on her personal space. Undeterred, I tell her that I work for an organization called Buklod. "We bring women together to discuss their lives and share ideas," I say. "You should come to our next meeting." She looks at me quizzically and asks, "What do you know about my life?" (…)

In 1984, Olongapo City was a thriving U.S. military base and my name was not Alma but "Pearly." I was a single-mother of two young children struggling to support my family by waitressing seven days a week. The clubs were always busy when the military ships came in.

As a child I dreamed of becoming an accountant. When my brother promised to help pay my tuition, I left Manila for Olongapo City where he lived. Once I arrived though, he admitted that he had no intention of helping me attend college. Instead, he hoped I would "strike it lucky" and marry an American serviceman so I could support our family. After a few months there, I grew frustrated by the lack of jobs and finally agreed to waitress near the U.S. Naval Base at Subic Bay. My brother tried to force me to accompany the servicemen when they requested my company, but I refused.

One day, a serviceman offered the manager a "bar-fine" for me. I refused, saying that I was just a waitress. The manager told me that if I didn't go, I would lose my job. He threatened to withhold my transfer documents, papers releasing me from his employment and allowing me to work elsewhere. I was scared that my children and I would end up homeless and hungry, so I reluctantly agreed. The American wanted to rent a hotel room, but I told him to give me the money he would spend on a room and accompany me home instead. I sent my children to my parents because I did not want them to see what their mother was doing to make a living. I tried to avoid doing this again, but my daughter fell ill and I needed money for her medical expenses.

During my four years at the club, I had about 30 American "boyfriends". In the early 1980s, there were no health programmes, and nobody knew how to use contraceptives. The 'Amer-Asian' child population boomed. I gave birth to my third child knowing he would never meet his father. Around that time, we started hearing about AIDS. The American guys would line up for condoms before disembarking their ships. However, some of them would just blow the condoms into balloons and toss them around. We couldn't require a customer to use a condom because he would say, "I paid good money" and get his way. (…)

In 1984, I befriended an American woman named Brenda Proudfoot, who was helping women escape prostitution and sex trafficking. She invited me to join a support group where I met others in similar situations. After several meetings I knew this was my chance to finally exit the hellish world of prostitution. In 1987, I co-founded Buklodng Kababaihan and spoke with women at the bars about our services. My employer grew frustrated with my absences, but I felt so empowered that I continued speaking out against injustices at work. I now knew my rights as a woman and a human being and was unwilling to compromise any longer. My employer fired me, calling me "a Communist". I was unable to find another job because he withheld my transfer permit, but thankfully, Buklod hired me as an organizer. The salary was low, but I jumped at the opportunity. I was so happy to be free from prostitution. (…)

Society's understanding of human trafficking and prostitution needs to change. In my country, people believe that prostitutes are criminals and buyers are the victims. This is wrong. When women are not given equal opportunities for employment or education, their options are limited, and they grow desperate. Because women are often viewed as powerless sex objects they are constantly driven into the sex industry. At times, I too believed that I only existed for men's pleasure. Filipina women are often referred to as "little brown fucking machines" by servicemen. Once I asked a customer, "Why do you like Filipina women so much?" He replied, "Because the women are cheap, way cheaper than Japanese women. And besides, you can do what you like. Here the women are always smiling. They pretend that they like it."

We need to change this thinking and educate young girls about the abuses of the sex industry, to let them know that they do have choices. Women are human beings, not commodities to be bought and sold. As I leave the videoke bar, I'm unsure if the young woman will attend our next meeting. She is one of thousands of prostituted Filipina women. The sex industry is a huge machine, and it's not easy to stop. As one survivor to another, I try to communicate that I understand their fears and pain. I try to tell my sisters that Buklod is trying to create a different future.

Globalization and the dismantling of trade barriers have facilitated trade between nations. While there are positive aspects to globalization, it also contributes to trafficking and the exploitation of vulnerable workers, particularly where corporations look for cheap sources of labour and lower production costs to satisfy the demand for cheap goods and products. Developing countries offer these sources of cheap labour and lower production costs, as their citizens often lack education and have little option but to accept low paying jobs and exploitive working conditions (see Bales, 2004). Furthermore, the increasing ease of transnational movement enabled by globalization can also facilitate trafficking. As Kara (2011, p. 68) notes, "[t]raffickers take advantage of the fact that movement in the globalized world is exceedingly difficult to disrupt".

The process of globalization is especially pronounced and entrenched in the world economy. An increasingly integrated world economy enables human trafficking to thrive. Just like the slavery of old, modern day trafficking of humans is a lucrative business that has only become more rewarding for traffickers with the advent of globalization. In fact, the trans-Atlantic slave trade of centuries ago epitomized economic globalization. Just as it was back then, human trafficking, as abhorrent as it is, remains a matter of supply and demand. To corroborate this stark and unfortunate economic reality, the ILO estimates that annual global profits generated from trafficking amount to around U.S. $32 billion (ILO 2008).

Polakoff submits that economic globalization has led to a form of "global apartheid" and a corresponding emergence of a new "fourth world" populated by millions of homeless, incarcerated, impoverished, and otherwise socially excluded people (Polakoff 2007). It is from this pool of "fourth world" denizens where victims of human trafficking are increasingly drawn. From this perspective, economic globalization is the prime culprit of the facilitation of an exorbitant number of vulnerable trafficking victims worldwide. More precisely, according to the U.S. Department of State's 2008 report, about 600,000 to 800,000 people-mostly women and children-are trafficked across national borders. In this age of globalization, one can only expect these numbers to escalate as the inequalities and the economic disparities between the developing and developed worlds continue at the present pace.

Globalization fosters interdependence between states for commerce and facilitates the transfer of commodities. Comparative advantage in goods and cheap labour in developing states has played a significant role in objectifying and exploiting humans for economic ends. In developing states where agrarian lifestyles once predominated, citizens are left without an education or the appropriate skills to compete in an evolving work-force. To a large extent, the lesser developed countries of the world have become the factories and workshops for the developed countries. A high demand for cheap labour by multinational corporations in developed countries has resulted in the trafficking and exploitation of desperate workers who, in turn, are subjected to a lifetime of slave-like conditions. (…)

The ultimate icon of globalization, the internet, has also proven to facilitate the trafficking of individuals. Traffickers can now, from the comfort of their own lairs, lure women into trafficking under the guise of mundane job advertisements in foreign countries.

Restrictive migration and labour laws can contribute to trafficking by creating obstacles to lawful migration. Impoverished and vulnerable migrants seeking to cross international borders in search of a better life may attempt to circumvent such restrictions by migrating irregularly and engaging the services of migrant smugglers, some of whom may turn out to be traffickers (on these dynamics see, eg, Koser, 2010).

In some cases, States have attempted to address this problem by creating lawful pathways for vulnerable migrants from neighbouring countries to take up employment opportunities, particularly if there are labour shortages (see Long, 2015). Unfortunately, passport and identification requirements, together with costs and delays in processing applications for entry, often inhibit the effectiveness of such approaches. Nor is there any assurance that lawful entry will protect vulnerable migrants from traffickers once they cross the border.

Similarly, restrictive labour laws for migrants often tie them to a particular employer/sponsor. If that employer proves to be dishonest or exploitive, it may not be permissible for the employee to switch to another employer without risking official sanctions. Legal avenues of redress, meanwhile, can be difficult as well, time consuming and expensive to access. Unscrupulous employers take advantage of these difficulties. The Kafala system, as a system of labour control, has been criticised in this context, as seen in Box 3.

In her Preliminary Findings in Kuwait in 2016, the Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons noted the following:

"The Kafala system, bounding every worker to a particular employer as a sponsor, creates a situation of vulnerability which favours abusive and exploitative work relationships. It happens that domestic workers are deprived of their documents and of their mobile phones, are prevented from communicating with their families and from establishing social relationships outside the family, are obliged to work long working hours, and are eventually mistreated and beaten. In this context, hundreds of them flee their employers every year…. In order to be successful in the struggle against trafficking, the government of Kuwait should also consider to deal with the general context of migration and labour regulations that produce social vulnerabilities. This is the reason why the Kafala system should be abolished and replaced by a different regulation, allowing migrant workers to enjoy substantial freedom in the labour market. Moreover, in line with the recent law acknowledging the rights of domestic workers, the area of domestic work should be placed under the competence of the Ministry of Labour and the Authority for Manpower, which implies full recognition of equal rights if domestic workers".

Conflict, oppression and natural disasters have displaced countless people who are then vulnerable to exploitation by traffickers and smugglers. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there were 25.4 million refugees in the world in 2018, over half of whom are under 18 years of age. In 2018, UNHCR stated that, furthermore, there are 68.5 million forcibly displaced people globally, a figure increasing at the rate of one person every three seconds. Both asylum seekers and those who are forcibly displaced often need to engage the services of migrant smugglers to leave their countries (Gallagher, 2015). As noted previously, smuggled migrants may become victims of traffickers.

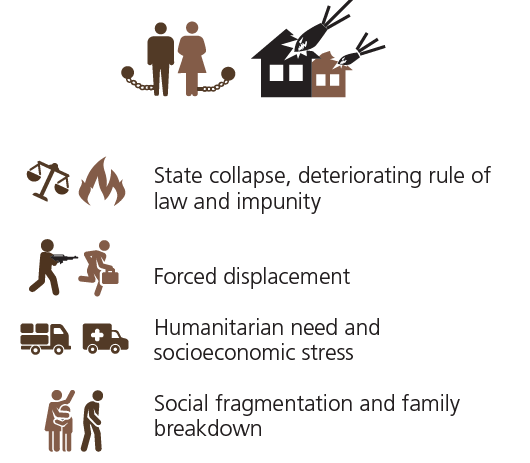

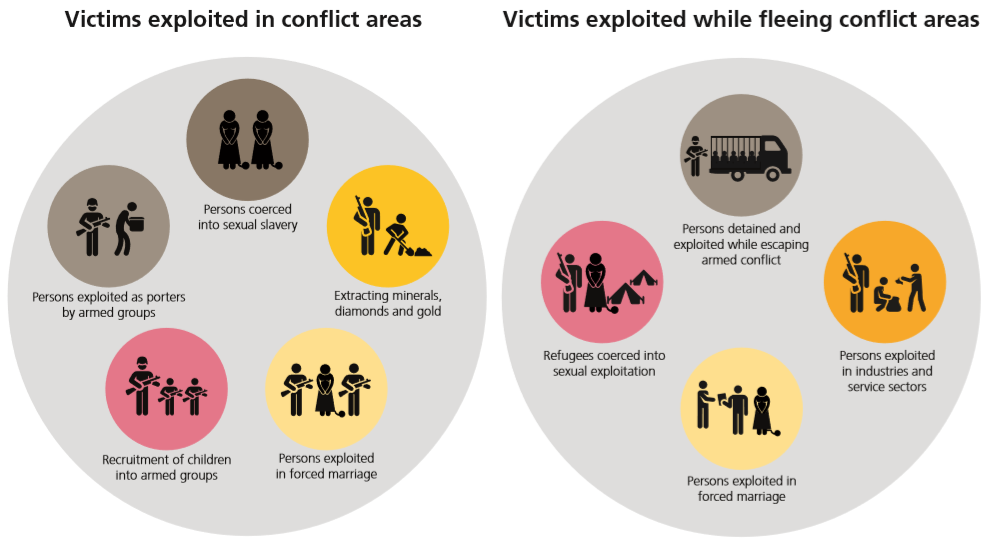

In civil wars and ethnic conflicts, oppressed groups may suffer a complete breakdown of legal protection, increasing their vulnerability and, at times, pushing them away from their community. The resulting displacement leads to isolation, thereby creating enabling conditions for traffickers to prey on their victims (see also UNODC, 2018). Figure 1 lists some factors that increase the vulnerability to trafficking in persons in armed conflict as well as examples of how armed conflicts contribute to trafficking.

When people think of sex trafficking, they often think of commercial sexual exploitation where traffickers and pimps profit monetarily from the exploitation of human beings. However, under the Palermo Protocol, the internationally agreed-upon definition of trafficking in persons does not necessarily require an exchange of money to have taken place.

In war-torn Uganda, the abduction of boys to become child soldiers has been widely reported on. However, the fate of thousands of Ugandan girls, who were abducted and sexually exploited, forced to become sex slaves for rebels and soldiers during Uganda's civil war, has received less attention. They, too, are victims of trafficking and their voices must also be heard. As a young child, my life was good and I felt happy. I spent many evenings playing netball and dancing with my friends. My family's home was located in Unyama, a village outside of Gulu, in northern Uganda. I am the youngest of four children, two boys and two girls. As a child, I helped fetch water and cook for my family, but I also attended primary school. My father was never home, so my mother and grandfather raised me. We were a happy family that loved each other. When I was nine years old, my life changed suddenly.

On the night of May 22, 2000, rebels with the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) descended on our home. My mother and I were asleep in our hut when they barged in and woke us up by kicking down the door. Five men caught us right away. One man held me down, ripped off my blouse, and tied me up. I watched in horror as another man beat my mother badly. One of the rebels brought in a large bag of posho-maize meal-and ordered me to carry it. They tied up my grandfather and others in my village and forced all of us to walk and walk without rest to an unknown destination. After a few days, the rebels allowed my grandfather to leave, but he could not even look into my eyes to say goodbye. He walked away in silence. The rebels told me not to be afraid because they would take me back home, but I didn't believe them. I feared they were going to kill me. The rebels didn't kill me, but they forced me to kill others. I was trained to fight and shoot a gun. At first, I refused, but they beat me and threatened me with death. The rebels made examples out of some of the children to warn the rest of us what would happen if we disobeyed their orders. The boys were forced to rape, and the girls got raped. All the girls were divided among the male fighters as "wives." The leaders believed the male fighters would escape if they did not have "wives" to fulfil their sexual desires.

When I was 10 years old, I was married against my will to a Brigade Commander. The first time he forced me to have sex I bled and cried a lot. I was in great pain, but my "husband" had a gun next to him and I had seen him use it before, so I tried to stop crying. Every day he called me and demanded sex. Whenever I tried to resist, he beat me to the point of paralysis. Sometimes I felt so weak because we had no food or water, but I had to go to him anyway. The Brigade Commander had a total of 20 "wives" - some were very young, but most were between 12 and 18 years old. If the rebels raided a village and abducted a beautiful girl, she would be forced to marry the Brigade Commander. Since I was also a soldier who fought, I was more respected than some of the other girls who were only "wives." When my "husband" would go away, I would stay with his other "wives" and keep them in line. I knew that if any of them ever escaped, I would be killed.

A year into my captivity, a big fight erupted not far from where we were being held between LRA members and Ugandan government soldiers. I decided to use the opportunity to run away, as I would rather die trying to escape than die in the bush as a sex slave. Two other girls ran with me, and we made it to the barracks where the government soldiers were staying. When we arrived, the guards took our guns and gave us clothes and food. After a while, they took us back to our villages. When I returned home, my mother accepted me despite my past. However, my neighbours and community were afraid of me and shunned me; they knew I was forced to commit unspeakable acts of violence. Life was difficult even at home. I suffered from extreme insomnia, haunted by memories of the rebels. I was still breathing, but somehow I didn't really feel alive. My mind kept replaying the past.

I tried to return to school when I was 12, but I couldn't concentrate on what my teachers were saying. I found other people who had suffered like me, but I still felt so alone. One day when I was 15, I was walking home from school when a man around 19 years old approached me and forcibly took me into his hut deep in the bush. I tried to fight the man, but he was too strong. No one was around to help me or hear my screams. When I went home, my mom chased me away, telling me to go back to the man since he was my husband now. I didn't want to go back to him; I wanted to go to school. However, I had nowhere else to go, so I returned to him and soon grew pregnant with my daughter. My family accepted me again since I was living with the man as his wife. I spent a year with my new "husband", but he drank too much alcohol. We would fight, and he would beat me badly for no reason. After one particularly vicious beating, I took my child and fled to my mother's home. I stayed at home for six months and then I heard about ChildVoice International. Since then my life has changed. I am very different now. I went to ChildVoice not speaking a word of English. During my time there, I learned English and skills such as catering, baking, and tailoring. I also found solace in my growing relationship with God.

After leaving ChildVoice, I found work in a bakery in Pece and met my current husband. Unlike my first husband, he is good to me and treats me as an equal. For the first time in my life, I have hope for the future and my children's future. Today, I believe I can do many good things if I find a way. I am much happier now and can even laugh sometimes. On most days, I can talk about the past without feeling fear and shame. My past no longer stops me from living my future. I want people to know what has happened here in Northern Uganda. Even though the fighting has ceased, men continue to abuse women. Those who have escaped from the bush should be able to return to school and learn some skills, so they can have a future. In my country, we do not provide enough support for child soldiers. Right now, there are only a few organizations to help us. Many of us survived the conflict, but we can do nothing but cry about our past since we have no family, food, money or skills. The government needs to provide more support for former child "wives" of the LRA rebels.

Corruption facilitates trafficking in persons in numerous ways. It helps by assisting traffickers to transport and exploit victims. It also negates attempts to investigate and prosecute traffickers, who may act with impunity due to the complicity or inaction of public officials. For instance, a border control officer may turn a blind eye to people without legal documents crossing the border accompanied by their trafficker. Reports indicate that some officials accept or extort bribes or sexual services, falsify identity documents, discourage trafficking victims from reporting their crimes, return victims to their traffickers or tolerate child prostitution and other trafficking activities at commercial sex sites (The Protection Project, 2013). A study conducted by Studnicka (2010) found that trafficking can be closely linked and even dependant on levels of official corruption. When corruption decreases and public institutions are strengthened, the incidence of trafficking may also decrease (p. 40).

Corruption deprives victims of the protection they would ordinarily expect to receive if the law was enforced and officials complied with their duties. Consequently, traffickers operate with impunity knowing that the risk of getting arrested, prosecuted and convicted is minor. Widespread systemic corruption provides opportunities for traffickers to operate with ease across international borders and evade prosecution.

In 2011, UNODC published an Issue Paper entitled The Role of Corruption in Trafficking in Persons, which provides a useful analysis of this topic. More information on corruption can be found in the fourteen modules of the University Module Series on Anti-Corruption.

Some social, religious and cultural practices make people vulnerable to traffickers. Harmful social practices include social exclusion and marginalization. The former relates to a lack of access to social rights and prevents groups from receiving the benefits and protection to which all citizens should be entitled. The latter includes discrimination in education, employment, access to legal and medical services, information and social welfare. It derives from complex factors, including gender, ethnicity and the low social status of certain groups. Social exclusion is especially relevant in the context of prevention of re-victimization and re-trafficking. Trafficked victims commonly face insurmountable barriers to rebuilding their lives when returning to their communities, including negative attitudes, condemnation and biases within those communities (see, e.g., the study by McCarthy, 2018).

In many communities, religious and cultural norms may affect the treatment of women and girls who may, due to gender-based discrimination, be more vulnerable to trafficking (see, e.g., Chuang 1998, pp. 68-73). For instance, certain cultural practices, such as arranged, early or forced marriages, but also temporary marriages, marriages by catalogue or mail order brides (where there is a lack of consent and, hence, an element of exploitation) can amount, or contribute, to trafficking in persons (see Module 13).

Many consumers demand cheap goods and services. Corporations meet that demand by sourcing goods and services from poorer nations, often using exploited labour. Examples include clothing and electronic goods, seafood, coffee, rice and narcotics. Attempts to modify consumer attitudes and spending habits have had limited success. Ultimately, consumers are unwilling to pay higher prices for goods sourced from a trafficking-free supply chain. Added to this is the demand from wealthier countries for organs for transplant operations, pornographic material involving child sexual exploitation, cheap commercial sex services and related sex tourism entertainment.

UNICEF USA, on its website for the End Trafficking Campaign, asks What fuels human trafficking? It states that "high demand drives the high volume of supply. Increasing demand from consumers for cheap goods incentivizes corporations to demand cheap labour, often forcing those at the bottom of the supply chain to exploit workers. Secondly, increased demand for commercial sex - especially with young girls and boys - incentivizes commercial sex venues including strip clubs, pornography, and prostitution to recruit and exploit children".